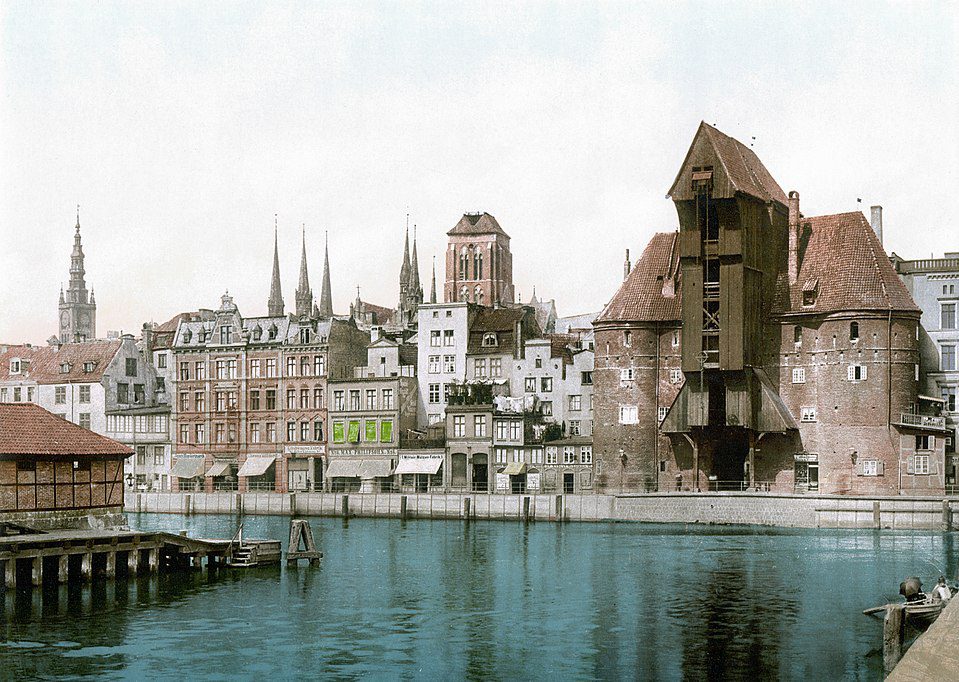

Standing at the mouth of the Motława River, where it flows into the Baltic Sea, Gdańsk has long been more than just a city—it is a convergence point, a meeting ground, a palimpsest of civilizations etched into bricks, stone, and canvas. For centuries, Gdańsk’s identity has been shaped not by a singular culture but by a dynamic and often fraught dialogue between peoples and empires. This polyphonic history—German, Polish, Dutch, Scandinavian, and Baltic—has endowed the city with a complex and vivid artistic legacy, one that resists easy categorization.

The story of art in Gdańsk is inseparable from the story of Gdańsk itself. A port city of strategic importance, Gdańsk rose to prominence as part of the Hanseatic League in the late Middle Ages. This powerful confederation of merchant guilds and market towns spanned the coasts of Northern Europe, linking cities like Lübeck, Hamburg, Riga, and Stockholm in a web of commerce. Through these mercantile arteries flowed not only goods—grain, amber, timber—but also ideas, tastes, and styles. Artistic innovation arrived in the city on ships, nestled alongside bales of cloth or barrels of beer.

The architecture of Gdańsk’s Main Town bears the stamp of this layered inheritance. Along Długi Targ—the Long Market—one can trace the evolution of European art history rendered in civic form: Gothic spires, Renaissance gables, Baroque facades, all jostling for attention. Yet these aren’t simply architectural flourishes. Each style represents a moment in the city’s shifting identity—its religious affiliations, political dominion, and cultural aspirations. Gdańsk was ruled at various times by the Teutonic Knights, the Polish crown, the Prussian Empire, and the Nazi regime, before becoming a key site of resistance during the fall of communism. Each epoch left its artistic imprint—sometimes in gilded altarpieces, sometimes in charred ruins.

While Gdańsk’s geographical location explains much of its historical importance, its social fabric is what made it an artistic crucible. This was a city of negotiation and contestation, where German burghers, Polish nobility, Jewish merchants, Dutch artisans, and Scandinavian sailors coexisted—sometimes uneasily, but always productively. Art in Gdańsk has often been hybrid in nature: Netherlandish altarpieces with Slavic iconography; Lutheran churches adorned with Baroque Catholic flair; Flemish-style portraiture depicting Polish magnates. Such juxtapositions were not anomalies—they were the norm. Gdańsk’s visual culture emerged from the productive friction between foreign influence and local tradition.

The city’s most enduring artistic landmarks echo these layers. St. Mary’s Church, the largest brick church in the world, exemplifies Gothic enormity fused with regional craftsmanship. The Neptune Fountain, a mannerist monument erected in the 17th century, reflects the city’s pride in its maritime prowess and its openness to classical allegory. The Golden House, with its opulent facade and intricate reliefs, tells a story of mercantile wealth and artistic cosmopolitanism. Each of these works is a statement—not just of aesthetic taste, but of identity and allegiance.

What makes Gdańsk’s artistic heritage especially poignant is its experience of destruction and rebirth. World War II ravaged the city. By 1945, more than 90% of the historic center lay in ruins, its architectural and artistic treasures obliterated by bombing and looting. Yet, in one of the most ambitious reconstruction projects of the 20th century, the Polish people meticulously rebuilt Gdańsk’s Old Town, using old photographs, paintings, and memories as blueprints. This act of restoration was not merely about bricks and mortar; it was a cultural resurrection. To walk through the city today is to experience a simulacrum that is paradoxically authentic—a copy imbued with original spirit.

Gdańsk also played a symbolic role in the modern art and cultural movements that shaped postwar Poland. It was here, in the Gdańsk Shipyard, that the Solidarity movement emerged in the 1980s, using posters, murals, and street performances to resist the totalitarian aesthetic of Socialist Realism. In recent decades, the city has become a hub for contemporary artists engaging with themes of memory, displacement, and identity—continuing the tradition of using art as a mirror for Gdańsk’s complex history.

This article will explore the evolution of art in Gdańsk across the centuries—from Gothic altarpieces to avant-garde installations—always with an eye toward the city’s unique position at the nexus of cultures. We will uncover the forgotten painters of the Hanseatic era, examine the influence of Dutch aesthetics on local craft, trace the trajectory of religious imagery through Reformation and Counter-Reformation, and examine how the trauma of war and the politics of memory have shaped artistic expression in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Gdańsk is not a city with a singular artistic identity. Rather, it is a mosaic—each tessera a fragment of influence, each era a layer of sediment. To study its art history is to engage with questions that reach beyond borders and time: How does a city remember itself? How does art survive upheaval? And what does it mean to belong—artistically and culturally—to a place that has always been in flux?

Medieval Foundations and Gothic Traditions

When one walks the cobbled lanes of Gdańsk’s Old Town today, the past is palpable. But to understand the roots of the city’s artistic identity, we must go back to the 13th and 14th centuries—a period when Gdańsk was transforming from a Slavic fishing settlement into a fortified urban center of international significance. This transformation was not just political or economic; it was visual. The earliest art of Gdańsk was inseparable from the spread of Gothic architecture, religious symbolism, and the city’s gradual incorporation into the Northern European Christian world.

The medieval art of Gdańsk cannot be separated from the region’s broader geopolitical shifts. During the 13th century, the Teutonic Knights—a German Catholic military order—established dominion over the area, constructing fortresses and bringing with them a wave of German settlers. Under their rule, Gdańsk was refounded and granted Lübeck law, aligning it legally and culturally with the powerful Hanseatic League cities of the north. This alignment brought access to the Gothic styles flourishing in cities like Lübeck, Bremen, and Bruges.

At the heart of Gdańsk’s medieval art stands St. Mary’s Church (Bazylika Mariacka), whose construction began in 1343 and stretched over 150 years. A colossus of brick Gothic architecture, the church is one of the largest of its kind in Europe. Its sheer scale—capable of holding up to 25,000 people—signals the city’s rising prosperity and ambition. But beyond its physical grandeur, St. Mary’s was a crucible of artistic endeavor. Inside, one finds a rich repository of late medieval religious art, including intricate wooden altarpieces, polychrome sculptures, and stained glass that would rival many continental cathedrals.

Among the treasures of St. Mary’s is the High Altar by Michael of Augsburg, a masterpiece of late Gothic carving completed in 1517. It exemplifies the kind of pan-European artistry flowing through Gdańsk at the time—an ornate tableau featuring saints, apostles, and scenes from Christ’s Passion, framed in intricate Gothic tracery. The attention to anatomical detail, facial expression, and spatial depth demonstrates the influence of the German and Netherlandish schools, particularly artists like Veit Stoss and Rogier van der Weyden.

Religious sculpture during this period was especially vibrant. In a city where the majority of inhabitants were deeply religious—both Catholic and later Lutheran—the need for devotional objects was immense. Woodworkers and sculptors specialized in creating life-sized crucifixes, Pietàs, and Marian figures. These artworks were not merely decorative; they were designed to evoke spiritual contemplation and penitence, part of a broader Christian worldview in which art served didactic and salvific purposes.

One notable example is the Beautiful Madonna of Gdańsk, a limestone sculpture from the early 15th century that once adorned the Dominican church. This statue embodies the “Schöne Madonnen” style—typified by graceful, S-shaped figures, serene expressions, and a gentle, almost courtly ideal of femininity. Though influenced by Prague and the Rhineland, Gdańsk’s Madonna is infused with a Baltic sensibility: sturdy, modest, yet not without elegance.

While sacred art dominated, civic and secular commissions began to appear in the late medieval period, especially as Gdańsk grew wealthier from trade. The Artus Court (Dwór Artusa), built in the 14th century and later remodeled, became a center of public life, guild meetings, and cultural display. It was filled with decorative elements—paintings, reliefs, tapestries—meant to demonstrate both the power of the city’s merchant class and its participation in a broader European artistic language. The Gothic hall with its vaulted ceilings was more than a meeting place; it was a stage for urban identity, a symbolic expression of Gdańsk’s autonomy and aspirations.

Guilds played a crucial role in sustaining the medieval art scene. The painters’, sculptors’, and goldsmiths’ guilds regulated artistic production, trained apprentices, and ensured high-quality standards. These organizations also commissioned altarpieces and public artworks to assert their civic presence and piety. While individual artist names from this period are often lost to history, their work survives in devotional objects, liturgical vessels, and architectural embellishments scattered across the city’s churches and museums.

It is also important to understand the role of iconography in shaping medieval Gdańsk’s visual culture. This was a time when images were potent spiritual tools. Saints associated with trade and protection—such as St. Nicholas, St. Barbara, and St. George—were particularly popular. Many of the altarpieces feature elaborate cycles narrating the lives of these saints, providing moral instruction through visual storytelling. In a largely illiterate society, these works functioned as public pedagogy, reinforcing religious orthodoxy while also showcasing local craftsmanship.

By the late 15th century, Gdańsk had established itself as not only a commercial power but also a hub of artistic production. Its Gothic churches, bustling workshops, and richly adorned guildhalls bore witness to a society increasingly confident in its cultural expression. Yet even at this stage, Gdańsk’s art remained deeply interwoven with external influences. The constant arrival of foreign artisans, combined with the export of local artworks to other Hanseatic cities, created a feedback loop of stylistic innovation.

This period also sowed the seeds of later transformations. The iconoclasm of the Protestant Reformation, which would sweep through Gdańsk in the early 16th century, would radically alter the use and meaning of religious imagery. But in the medieval centuries, art in Gdańsk was a conduit of faith, community, and status—a mirror held up to a society finding its place in the northern Gothic world.

Renaissance Flourishing under Hanseatic Wealth

The Renaissance reached Gdańsk not with the thunder of revolution but on the quiet rhythm of merchant ships. By the early 16th century, Gdańsk—firmly embedded in the Hanseatic trade network—was one of the wealthiest cities on the Baltic Sea. Its prosperity did not only fund warehouses and granaries; it nourished a blossoming of the arts. While the Italian Renaissance had its roots in the courts of Florence and Rome, Gdańsk’s version was decidedly northern, shaped by pragmatic burghers, Dutch painters, and itinerant craftsmen. The city’s Renaissance was as much a civic enterprise as it was an artistic movement.

At the heart of this flourishing stood the city’s merchant elite. These were men who dealt in grain, amber, salt, and timber, men who balanced the books of trade while cultivating a taste for the new intellectual and artistic currents from the South. Gdańsk’s patricians commissioned buildings, paintings, sculptures, and public monuments that reflected not only their personal wealth but also their alignment with Renaissance ideals: civic pride, classical learning, and human dignity.

Architecture was the first and most visible expression of this cultural shift. The Gothic structures of the medieval period began to be retrofitted with Renaissance details: scrollwork, pilasters, triangular pediments, and decorative friezes that spoke of classical antiquity—but through a distinctly Northern European lens. The façades of townhouses along Długi Targ were adorned with reliefs of mythological scenes, coats of arms, and allegorical figures, each reflecting a blend of humanist learning and mercantile assertion.

One of the most iconic examples of Renaissance architecture in Gdańsk is the Golden Gate (Złota Brama), completed in 1612 by Abraham van den Blocke, a Flemish architect who played a pivotal role in reshaping the city’s skyline. The gate, a triumphal arch adorned with statues symbolizing Peace, Freedom, Wealth, and Fame, echoed the civic ideals of the time. Its style—Dutch Mannerism with classical motifs—was a testament to the cosmopolitan artisans who now made Gdańsk their home.

Equally important was the Artus Court, originally built in the Gothic style but extensively renovated in the Renaissance period. Named after the legendary King Arthur and modeled after similar halls in Lübeck and Riga, the Court became a meeting place for the city’s elite—a venue where art, politics, and commerce intersected. The Court’s lavish interior was filled with allegorical paintings, wooden sculptures, and an enormous tiled stove over 10 meters high, covered in more than 500 glazed tiles depicting kings, emperors, and Biblical scenes. This was not simply decoration; it was a visual encyclopedia of power, morality, and history.

In painting, Gdańsk experienced a golden age during the Renaissance, though much of it was indebted to foreign artists and imported works. Local patrons often commissioned altarpieces and portraits from Dutch and Flemish masters, leading to an influx of stylistic influence from the Low Countries. Religious themes remained dominant, but they now carried the hallmarks of Renaissance naturalism: spatial perspective, individualized faces, and complex, balanced compositions.

One of the standout figures in this milieu was Anton Möller, a German painter active in Gdańsk in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Möller’s work exemplified the synthesis of Renaissance form with local themes. His altarpieces, portraits, and ceiling paintings demonstrated a remarkable command of anatomy, architectural perspective, and iconographic complexity. In works like The Judgment of Solomon or Allegory of Gdańsk, Möller did more than beautify public and private spaces—he embedded in them moral lessons, civic allegories, and a strong visual identity for the city.

Another central figure was Herman Han, a court painter to the Polish king who also worked extensively in Gdańsk. His paintings, often monumental in scale, blended Mannerist elegance with emotional immediacy. His altarpiece at the Church of St. John, depicting the Assumption of Mary, is a study in Renaissance dynamism and theological drama, rendered with precise color harmonies and graceful composition.

Renaissance art in Gdańsk was not limited to religious or civic commissions. Portraiture emerged as a major genre, driven by the merchant class’s desire for legacy and status. These portraits often depicted sitters against neutral backgrounds, dressed in fine clothing, holding books or scrolls—symbols of both wealth and humanist education. Though often painted by anonymous artists, these works reveal a growing appreciation for individual identity, personal expression, and the subtle psychology of the human face.

But perhaps the most emblematic Renaissance creation in Gdańsk is the Neptune Fountain, unveiled in 1633. Designed by Abraham van den Blocke and cast by local artisans, the fountain stood not only as a celebration of Gdańsk’s maritime identity but also as a symbol of its openness to classical mythology and Renaissance symbolism. Neptune, the god of the sea, presides over the city’s central square with his trident raised, commanding the waters that had brought Gdańsk its fortune. Around him, Baroque ornamentation spirals upward—an aesthetic bridge to the next artistic epoch.

The Renaissance in Gdańsk was not a break from the past but an expansion. Gothic churches remained in use and were embellished rather than replaced. Medieval guild traditions persisted, but now operated in a broader market of stylistic exchange. Artists continued to come from the Netherlands, Germany, and even Italy, while local talents increasingly absorbed and reinterpreted foreign ideas. What emerged was a uniquely Gdańsk version of the Renaissance—anchored in commerce, steeped in humanist thought, and visually expansive.

This era laid the groundwork for the artistic flowering that would follow in the Baroque period, when Gdańsk’s allegiance to both faith and ornament would find new and more expressive forms. But the Renaissance remains a defining chapter in the city’s visual history—a moment when humanist ideals found expression not only in books and schools but on buildings, canvases, and street corners.

Baroque Brilliance and Counter-Reformation Impact

As the 17th century unfolded, Gdańsk found itself swept into the flamboyant drama of the Baroque. This was not a subtle transition. Where the Renaissance had pursued balance and reason, the Baroque embraced movement, theatricality, and emotional depth. Gdańsk, already a city of grandeur and layered identities, adopted the Baroque with enthusiasm—especially in its churches, civic buildings, and public sculpture. But this wasn’t merely an aesthetic choice. The Baroque era in Gdańsk was inseparable from the spiritual convulsions of the Counter-Reformation, the pressures of external warfare, and the city’s continued struggle to assert its autonomy.

Though formally under the sovereignty of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Gdańsk in the 17th century remained fiercely independent, ruled by a powerful merchant council and shaped by both Lutheran and Catholic influences. This religious duality played a crucial role in defining the city’s Baroque art. While much of Catholic Europe was embracing Baroque as the visual language of the Counter-Reformation, in Gdańsk the style was adopted by both confessions—albeit with different emphases.

The city’s Catholic churches became prime canvases for Counter-Reformation aesthetics. In these spaces, art was no longer merely devotional—it was polemical. Lavish altarpieces, ceiling frescoes, and sculptural programs sought to dazzle the viewer, guiding them toward orthodoxy through emotional engagement and sensory immersion. One of the most striking examples is the interior of St. Nicholas Church, which underwent a Baroque transformation under Dominican guidance. Rich gilding, pulsing light, and cascading angels created a celestial atmosphere intended to overwhelm and convert.

Perhaps the most influential artist of this period in Gdańsk was Andreas Schlüter, a native son born in the city in 1660, who would go on to become one of the leading sculptors and architects of the Northern Baroque. Though he spent much of his career in Berlin, his early work in Gdańsk laid the foundation for his monumental style. His Funeral Monument of Field Marshal Heidenreich von Rehbinder in the Church of St. Catherine is a masterclass in expressive realism: the figure of the marshal lies in eternal rest, while allegorical figures of Victory and Time encircle him, rendered with a tactile intensity that was new to Gdańsk.

Schlüter’s style exemplifies the Baroque’s tension between the earthly and the divine. It captures that fleeting moment where sorrow becomes sublime—where mourning is elevated through art into a shared, transcendent experience. This emotional register became a hallmark of the Gdańsk Baroque, especially in funerary art, where tombs became elaborate visual sermons on mortality, faith, and legacy.

Another towering figure of the era was Herman Han, whose altarpieces bridged the late Renaissance and early Baroque sensibilities. His masterpiece, the Coronation of the Virgin Mary at the Cathedral in Pelplin (not far from Gdańsk), is a swirling composition of saints, angels, and divine light, evoking the ecstatic fervor promoted by the Jesuits. Han’s work shows the influence of Italian and Flemish painters like Rubens and Carracci, yet it remains rooted in the Baltic world, marked by a cool palette and meticulous craftsmanship.

Baroque architecture also transformed the city’s profile. Private homes of wealthy merchants began to boast elaborately decorated portals, stucco reliefs, and ornate gables. The Royal Chapel (Kaplica Królewska), built in 1678–1681 by Tylman van Gameren, stands as a jewel of Baroque design in the city. Commissioned by King John III Sobieski for the Catholic community during a time of religious tension, the chapel is a masterful fusion of Dutch, Italian, and Polish architectural motifs. Its octagonal dome, symmetrical plan, and gilded interiors announce a new architectural language—one of power, piety, and princely magnanimity.

Public art flourished too, especially as a tool of civic pride. Fountains, statues, and monuments began to serve not just as embellishments but as ideological instruments. The Neptune Fountain, though conceived earlier, was incorporated into the Baroque vision of the city square, surrounded by rich façades and theatrical perspectives. It became an emblem of Gdańsk’s maritime supremacy and classical aspirations—Neptune, god of the seas, watching over a city that had made its fortune on the waves.

Despite the exuberance of its art, the 17th century was also a time of considerable hardship for Gdańsk. The city endured Swedish invasions, economic downturns, and plague. In this context, Baroque art took on a consolatory function. Church interiors often depicted not just divine glory but scenes of suffering, martyrdom, and redemption. In this way, Baroque art in Gdańsk served a dual purpose: it was both aspirational and cathartic, a means of processing trauma through visual opulence.

Another notable feature of the Gdańsk Baroque was its cosmopolitanism. Artists and architects from the Netherlands, Italy, and Germany found ready commissions in the city, and local workshops absorbed these influences to create hybrid forms. The Baroque in Gdańsk is thus not a pure strain of a style but a mosaic of European elements filtered through local traditions. Flemish chiaroscuro meets Slavic iconography; Italianate façades crown Teutonic walls.

This hybridity was not accidental—it was reflective of Gdańsk’s position at the edge of empires and at the center of trade. The city’s visual culture in the Baroque era tells a story of negotiation: between faiths, between local and foreign, between decay and splendor. As the century wore on, the intensity of the Baroque would give way to the rationalism of the Enlightenment, but its imprint on the city’s churches, palaces, and tombs remained indelible.

Today, the Baroque legacy in Gdańsk can be seen in surviving interiors, carefully restored architectural details, and the continued use of religious art in sacred spaces. But perhaps more importantly, it survives in the city’s sense of theatricality—its ability to perform history, to stage its identity in stone and stucco. In the swirling clouds of a painted ceiling, the rippling musculature of a funeral effigy, or the gilded glow of an altarpiece, one finds a city that, in its darkest hours, turned to art for affirmation, salvation, and remembrance.

Dutch and Flemish Influences – Maritime and Merchant Imagery

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the golden age of Dutch and Flemish art swept across Northern Europe like a visual tide—and in Gdańsk, that tide found a welcoming shore. As a major Hanseatic port city, Gdańsk maintained intense commercial and cultural ties with the Low Countries, importing not only goods like textiles, spices, and books but also canvases, engravings, and the artists themselves. These interactions transformed the way Gdańsk’s burghers saw their world—and how they chose to represent it.

The Dutch Republic and Flanders were, at this time, the artistic powerhouses of Europe. Antwerp and Amsterdam produced painters whose work set the standard for realism, perspective, and genre innovation. While Italy offered the grandeur of history painting and religious narrative, the Netherlands popularized a quieter revolution: still lifes, landscapes, seascapes, and intimate domestic scenes. These themes resonated deeply in Gdańsk, a city whose own fortunes were tied to the rhythms of the sea and the sanctity of the household.

Gdańsk merchants, many of them ethnically German but also Polish and Dutch, began collecting paintings in earnest during the late Renaissance and into the Baroque era. They often favored Dutch and Flemish works, which could be purchased via intermediaries in Lübeck, Hamburg, or directly through visiting traders. These artworks were not merely decorative; they were statements of wealth, refinement, and global engagement. A still life with lemons, Chinese porcelain, and nautilus shells signified more than an aesthetic preference—it was a coded inventory of mercantile success.

Domestic interiors in Gdańsk reflected this appetite for Northern realism. In the tall, narrow merchant houses lining the Long Market, paintings hung alongside Delft tiles, wood-paneling, and polished oak furniture. Works attributed to the circles of artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder, Frans Francken, or Pieter Claesz were prized, while copies and adaptations were also produced by local artists trained in the Dutch manner. Art was becoming more accessible and personal—no longer confined to the altar or the palace but entering the parlor and dining room.

One particularly popular genre was marine painting. For a city whose identity was inseparable from its harbor, shipyards, and riverbanks, the maritime canvas became a kind of civic icon. Dutch painters like Ludolf Bakhuizen or Willem van de Velde—who specialized in stormy seascapes and naval battles—were admired not only for their technical prowess but for their romantic rendering of sea power and navigation. Local artists in Gdańsk soon followed suit, producing views of the port, depictions of merchant vessels, and imagined naval scenes that celebrated both commerce and courage.

Portraiture also flourished under Dutch influence. Gone were the rigid, idealized figures of earlier centuries; in their place came more naturalistic depictions—often three-quarter length, against neutral or symbolic backgrounds, with rich yet restrained clothing. These portraits emphasized not lineage alone but intellect, morality, and civic virtue. Books, scrolls, globes, and compasses served as props, framing the sitter not as aristocrat but as citizen and scholar. The Protestant ethos of modesty and industriousness often shaped these commissions, particularly among the city’s Lutheran elite.

One fascinating subset of this influence was the rise of genre scenes—depictions of everyday life, such as family meals, street markets, or moral allegories framed as domestic anecdotes. These scenes, drawn from the Flemish tradition, served dual purposes: they entertained and they instructed. In a Gdańsk home, a painting of a tavern brawl or a woman with scales could function as both decoration and subtle sermon on vice and virtue. These works helped shift the role of art from the liturgical to the lived—a shift aligned with Protestant sensibilities and mercantile values.

In addition to paintings, printmaking played a vital role in the dissemination of Dutch and Flemish imagery throughout Gdańsk. Engravings by Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, and later Rembrandt van Rijn circulated widely, copied by local artists or simply pinned to walls. These prints, often depicting Biblical scenes, mythological subjects, or scenes of urban life, made sophisticated visual culture available to a broader audience and influenced the compositional grammar of regional painters.

But the influence of the Low Countries wasn’t limited to painting. Decorative arts—including silverwork, cabinetry, and ceramics—also bore the stamp of Dutch taste. Gdańsk goldsmiths, who had long been among the finest in Central Europe, adopted Dutch repoussé techniques and baroque flourishes. Dutch tiles adorned fireplaces and stairwells; tulip motifs appeared in wood carving and embroidery. Even Gdańsk’s furniture evolved under this influence, with high-backed chairs and inlaid cabinets echoing Amsterdam’s domestic splendor.

This period also saw the rise of the kunstkammer—the cabinet of curiosities—in Gdańsk’s elite homes. Inspired by Flemish and German collecting practices, these rooms or display cabinets were filled with natural specimens, exotic artifacts, scientific instruments, and miniature artworks. They reflected the humanist spirit of inquiry and the Protestant valorization of worldly knowledge. Paintings of such collections, popularized by artists like Frans Francken, sometimes adorned the walls of the very rooms they depicted, creating a recursive aesthetic of contemplation and possession.

Yet the Dutch and Flemish influence on Gdańsk was not merely one of imitation—it was dialogical. Local artists adapted imported styles to their own narratives, combining Baltic landscapes with Netherlandish techniques, or inserting familiar symbols—like the crane, the ship, the Gdańsk lion—into borrowed compositions. This interplay created a distinct visual dialect: a Gdańsk style that spoke Dutch with a regional accent.

Importantly, this artistic dialogue reinforced Gdańsk’s self-image. In a period marked by political contestation (between the Polish Crown, Prussia, and Sweden) and religious friction, visual culture provided a means of asserting continuity, prosperity, and cultural alignment with Europe’s artistic centers. To display a Flemish-style still life or marine painting was to declare allegiance to a broader world of Protestant, humanist, mercantile modernity.

Today, traces of this influence can still be seen in Gdańsk’s museums, notably the National Museum in Gdańsk, which houses Dutch and Flemish works alongside regional painting schools. Private collections, restored merchant houses, and ecclesiastical holdings continue to reveal the extent to which Gdańsk absorbed and reinterpreted the artistic language of the Low Countries.

In the end, the Dutch and Flemish presence in Gdańsk’s art history is not just a story of aesthetic taste—it is a testament to cultural exchange, to the flow of images and ideas across seas, and to the enduring human desire to capture prosperity, piety, and identity on canvas.

18th-Century Decline and Enlightenment Echoes

By the dawn of the 18th century, Gdańsk’s golden age was beginning to dim. The bustling port city, once one of the wealthiest in Europe, found itself increasingly outpaced by new centers of power and trade. The Hanseatic League was in decline, Sweden’s Baltic ambitions cast a long shadow over the region, and Gdańsk’s political autonomy within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth grew more precarious. In the arts, this century is often viewed as a period of stagnation or decline—but this is only part of the story. The 18th century in Gdańsk also witnessed the quiet arrival of Enlightenment ideas, subtle shifts in taste, and the persistence of local craftsmanship in the face of growing uncertainty.

The architectural exuberance of the Baroque gave way to more measured and decorative styles—Rococo and early Neoclassicism—as Gdańsk’s aesthetic turned inward, reflecting a world where grand ambitions were tempered by introspection. Churches continued to be decorated, but the monumental altarpieces and funerary sculptures of the 17th century were now replaced by lighter, more ornamental designs. Pastel hues, stucco garlands, and elegant arabesques characterized many interior renovations. The Royal Chapel, for instance, though built during the Baroque era, was redecorated in line with Rococo sensibilities, its gilded interior softened by curling volutes and putti.

This shift mirrored a broader trend in Europe: the decline of absolutist monumentality and the rise of private taste. In Gdańsk, this meant that artistic patronage moved increasingly from public institutions and churches to the private sphere. Wealthy burghers and patricians continued to commission portraits and decorative objects, but now with an emphasis on refinement and domestic comfort rather than civic or religious spectacle. Art became more intimate—mirroring the salons and cabinets where Enlightenment ideals were quietly debated.

The portraiture of this era reflects these changing values. Artists emphasized gentility, elegance, and intellectual gravitas. Sitters were portrayed with books, musical instruments, or scientific tools, signaling a shift from dynastic pride to enlightened individuality. Though fewer painters from this period achieved lasting fame, local workshops continued to produce competent, sometimes exquisite work. Daniel Schultz the Younger, while active earlier in the century, was one of the last Gdańsk artists to bridge Baroque bravura with Rococo grace.

Scientific illustration and cartography also flourished in this period, driven by Enlightenment interests in observation, classification, and empirical knowledge. Gdańsk’s role as a publishing center—especially for atlases, botanical treatises, and religious tracts—sustained a demand for skilled engravers and illustrators. These artisans produced finely detailed images of everything from sea creatures to city plans, often blending artistry with technical precision.

Guilds, though weakened by economic and political instability, remained active, particularly in the decorative arts. Silversmiths and cabinetmakers continued to uphold Gdańsk’s reputation for fine craftsmanship. Rococo silverware from Gdańsk, with its undulating lines and floral motifs, remains highly prized today. Similarly, furniture from the era—often combining Baltic woods with Dutch and French design elements—offers a tangible glimpse into the evolving tastes of the city’s elite.

Yet this was also a century of loss. The Great Northern War (1700–1721) devastated the region, and Gdańsk, long a neutral city, suffered occupations, blockades, and plundering. Economic decline followed, exacerbated by competition from emerging ports and the gradual erosion of Gdańsk’s privileges. By mid-century, the once-thriving artistic exchanges with Amsterdam and Antwerp had slowed to a trickle. The city’s intellectual life, too, was increasingly isolated from the Enlightenment salons of Berlin, Paris, and Warsaw.

Still, the spirit of the Enlightenment found expression in subtle ways. The rise of secular themes in art—portraits, landscapes, allegories of knowledge and reason—marked a turn away from ecclesiastical dominance. Philosophical societies and masonic lodges began to appear in Gdańsk, patronizing art and architecture that reflected their values: symmetry, restraint, and rational beauty. Late in the century, the Neoclassical style began to take hold, visible in the design of public buildings and tombs. The emphasis on order, clarity, and classical reference points mirrored the growing influence of Enlightenment aesthetics.

One noteworthy development was the increasing importance of art education. The Enlightenment ideal of cultivating the mind extended to drawing and design, which were now seen as essential components of a learned gentleman’s upbringing. Some local academies and private tutors began offering instruction in the fine arts, and talented young artists were occasionally sent abroad to study in Berlin or Vienna—though the lack of centralized institutions meant Gdańsk lagged behind cities like Kraków or Warsaw in producing a coherent national school of art.

By the end of the century, the First Partition of Poland (1772) and the growing threat of Prussian dominance loomed over the city. Gdańsk’s autonomy was increasingly under siege, and with it, the civic identity that had once fueled so much artistic production. The final years of the 18th century were marked by both cultural resilience and a creeping sense of nostalgia—a longing for the vibrant city that Gdańsk had once been.

And yet, this period planted seeds that would later bloom. The aesthetic restraint of the Rococo and Neoclassical movements, the emphasis on individual virtue and empirical observation, the quiet persistence of craftsmanship and illustration—all laid a foundation for the 19th-century resurgence in Romanticism and national identity. Even in decline, Gdańsk remained a city of images—images not of grandeur perhaps, but of continuity, grace, and introspective beauty.

19th-Century National Romanticism and Historicism

The 19th century was a time of ideological flux and national awakening across Europe, and Gdańsk stood at the turbulent crossroads of these transformations. With the final partitions of Poland (culminating in 1795), Gdańsk was absorbed into the Kingdom of Prussia and stripped of its former autonomy. As the Napoleonic Wars reshaped the continent, the city briefly became the Free City of Danzig (1807–1814), only to be re-annexed by Prussia after Napoleon’s defeat. These political upheavals—and the accompanying questions of identity, memory, and belonging—left a deep imprint on the city’s art and architecture.

In this fraught environment, National Romanticism emerged as a powerful cultural force. Across Central and Eastern Europe, artists and intellectuals turned to the past to rediscover, or invent, a sense of national heritage. In Gdańsk, this movement was layered and contradictory: for some, it meant a return to Germanic medievalism; for others, it meant reviving Polish cultural traditions. Art became the battleground for contested memories, and the city’s visual culture reflected this ideological tension.

One of the primary manifestations of 19th-century nationalism in Gdańsk was the restoration of Gothic and Renaissance buildings, driven by the idea that architecture could serve as a repository of historical truth. Inspired by thinkers like Johann Gottfried Herder and later by the Gothic Revival movement in England, architects in Gdańsk began to “recover” the city’s medieval character. But this recovery was not purely documentary—it was interpretive, idealized, and often politicized.

The St. Mary’s Church, for instance, underwent significant restoration work aimed at recapturing its perceived Gothic purity. Missing elements were reconstructed, façades were cleaned, and Baroque additions were sometimes removed in favor of a medieval aesthetic that aligned with romanticized notions of national heritage. The same was true of other historic buildings, such as the Artus Court, which became a showcase for neo-Gothic interiors and heraldic symbolism. These restorations were often supported by Prussian officials and German cultural institutions, reflecting their vision of Danzig as a proudly Germanic city.

At the same time, painting and illustration in Gdańsk began to reflect the themes of national history, myth, and rural life. While there was no singular “Gdańsk School” of painting, the influence of German Romantic artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and Karl Friedrich Schinkel echoed in the city’s artistic circles. Landscapes became more symbolic than literal—misty riverbanks, ruined castles, and stormy skies became metaphors for the nation’s fate and the soul’s yearning for transcendence.

In Polish circles—especially among artists and intellectuals who had ties to Gdańsk but lived in exile—art became an act of resistance. Though official Prussian policy discouraged overt displays of Polish national culture, the Romantic nationalist movement persisted through poetry, music, and visual art. Painters like Artur Grottger and Józef Chełmoński, though based elsewhere, influenced artists in Gdańsk through their emotive historical scenes and depictions of Polish peasant life. These works, often printed and circulated clandestinely, helped foster a sense of shared memory and cultural continuity among Poles in and around Gdańsk.

Another important development in the 19th century was the rise of historicism, particularly in public architecture and monuments. This movement, which looked to the past for aesthetic and moral inspiration, resulted in a wave of buildings designed in neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, and neo-Baroque styles. These were not mere copies but reimaginings—structures that aimed to convey continuity and gravitas. The Gdańsk Main Railway Station, built in the late 19th century, exemplifies this trend: a vast, fortress-like complex adorned with turrets and decorative gables that suggest a lineage with the city’s medieval past, even as it embraced the technological modernity of steam travel.

Public sculpture also became a prominent medium for expressing identity. Monuments to historical figures, military heroes, and mythic symbols were erected across the city. These included statues of Kaiser Wilhelm I, Frederick the Great, and allegorical representations of Victory and Freedom. Each monument was a statement—a visual assertion of who owned the city’s history, and by extension, its future.

At the same time, museums and historical societies were established to collect, catalog, and display Gdańsk’s artistic and material heritage. The Danziger Stadtmuseum, founded in the late 19th century, assembled a wide array of artifacts: altarpieces, silverware, maps, textiles, and guild emblems. While these institutions aimed to preserve the city’s legacy, they also curated a specific narrative—often emphasizing German craftsmanship and Hanseatic order while marginalizing Polish and Baltic contributions.

Yet, beneath the official narrative, local artisans and collectors quietly maintained traditions that resisted cultural homogenization. Polish families preserved folk art, devotional icons, and family portraits that told a different story. This underground current of cultural resistance would later find full expression in the early 20th century, but its roots lay in this 19th-century moment of tension and duality.

Interestingly, the 19th century also saw the rise of photography in Gdańsk, which opened new ways of documenting the city’s architecture, daily life, and social rituals. Studios emerged to cater to the middle class, offering portraits and cityscapes that were both keepsakes and statements of identity. These early photographs, many now housed in archival collections, provide invaluable glimpses into the visual culture of a city negotiating its layered past.

By the end of the century, the ideological divisions in Gdańsk’s artistic world had become increasingly entrenched. The Polish national revival and the German imperial project competed not only in politics and education but in the very images and buildings that defined the urban landscape. Art was no longer just a reflection of culture—it had become a tool of cultural assertion.

Yet this artistic ferment, however polarized, ensured that Gdańsk remained a dynamic and image-rich city. Whether in the form of a Gothicized façade, a heroic battle painting, or a pastoral scene infused with Romantic melancholy, 19th-century art in Gdańsk offered its citizens ways to make sense of the past and imagine new futures. It was a period of looking backward in order to move forward—a practice that would take on new urgency in the face of the 20th century’s upheavals.

Modernism and the Interwar Period

The interwar years (1918–1939) were a time of transformation for Gdańsk—politically precarious, culturally vibrant, and artistically dynamic. After World War I and the Treaty of Versailles, the city became the Free City of Danzig, a semi-autonomous city-state under the protection of the League of Nations. This peculiar status—a kind of political no-man’s land between Germany and Poland—created both tension and opportunity. It was a city divided in loyalty but fused in geography, where competing narratives of identity played out not only in policy and propaganda, but in paint, poster, and public space.

Modernism in Gdańsk did not announce itself with the shock of a rupture; rather, it emerged gradually, entangled with the city’s cultural pluralism. On one side were the German-speaking majority, who still considered the city part of the greater German cultural orbit and supported traditional academic and historicist styles. On the other were Polish intellectuals, artists, and institutions, who saw Danzig as a city of deep Polish roots and sought to inscribe a modern Polish identity into its urban and artistic fabric. Between them was a third current—international modernism, which eschewed national boundaries in favor of abstraction, experimentation, and universalist ideals.

One of the key vehicles for modernist expression was graphic design and print culture. Gdańsk became a hub for avant-garde poster art, especially in the realms of advertising, film, and political messaging. Bold typography, photomontage, and constructivist layouts appeared on street corners and in shop windows, echoing similar trends in Warsaw, Berlin, and Moscow. Polish and German artists alike embraced the new aesthetics of mass communication, experimenting with form, color, and messaging to capture the speed and instability of the modern age.

The rise of Polish modernism in the Free City was particularly notable in schools and cultural associations supported by the Polish minority. Institutions such as the Macierz Szkolna (Polish Educational Society) promoted art education that emphasized contemporary Polish styles, informed by the Kapist movement and figures like Władysław Strzemiński, Tadeusz Makowski, and Zofia Stryjeńska. While most of these artists were based outside of Gdańsk, their work circulated through exhibitions, publications, and pedagogical materials, influencing young local artists who sought to create a distinctly Polish modernist language.

At the same time, the German art scene in Gdańsk was deeply engaged with the broader currents of Expressionism, Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), and Bauhaus functionalism. Painters and designers influenced by the likes of George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Paul Klee explored the urban psyche, the trauma of war, and the alienation of modern life through distorted forms, stark compositions, and a biting political edge. Artists working in this vein often faced pushback from conservative institutions, but their presence signaled a new kind of artistic courage—a willingness to document disillusionment and disorder.

Architecture in the interwar period also reflected these stylistic shifts. While parts of the old town remained steeped in historicist nostalgia, new neighborhoods and public buildings embraced modern materials and minimalist geometries. Apartment blocks and commercial structures in the Wrzeszcz and Oliwa districts, for example, bear the clean lines and functional forms associated with International Style modernism. Architects experimented with steel, concrete, and glass, designing structures that reflected both optimism and pragmatism.

One of the most emblematic buildings of the era was the Polish Post Office in Gdańsk, a functionalist design that doubled as a political and cultural symbol. More than just a workplace, it became a flashpoint for Polish identity and would later acquire tragic significance during the Nazi invasion in 1939. The building’s clean lines, rational design, and civic importance made it an icon of modern Polish presence in a contested city.

Photography, too, came into its own during this period. Gdańsk’s photographers—both amateur and professional—documented the city’s contrasts: its Gothic ruins and steel cranes, its market squares and military parades, its Catholic processions and socialist rallies. The Neue Sachlichkeit approach to photography, with its sharp focus and documentary realism, found fertile ground in a city where the urban landscape was both beautiful and brittle.

In parallel, artists of all backgrounds grappled with the psychological toll of modern life—loss, dislocation, industrialization. The First World War had shattered old worldviews, and Gdańsk, positioned between empires and identities, became a microcosm of this upheaval. Artworks from the period often convey a sense of fragmentation and yearning, oscillating between utopian abstraction and gritty realism.

Though no single art movement dominated, the pluralism of the interwar years gave rise to an extraordinarily diverse visual culture. One could find Bauhaus-inspired furniture in a Polish teacher’s apartment, German expressionist lithographs in a gallery window, and folkloric woodcuts on sale at a Sunday market—all within a few city blocks. This overlapping of styles, languages, and ideologies was both the strength and the tension of Gdańsk’s interwar art world.

Exhibitions, salons, and art associations flourished despite the political instability. The Association of Polish Artists in Gdańsk hosted events that showcased modernist painting and sculpture, while German-speaking artists organized their own exhibitions in venues supported by the Free City government. Cultural journals published criticism, manifestos, and reproductions of new work, helping Gdańsk stay connected to the wider European avant-garde.

Yet even as the city’s artistic landscape thrived, dark clouds gathered on the horizon. Rising nationalism, anti-Semitism, and the radicalization of politics began to intrude on artistic freedom. By the late 1930s, Nazi ideology increasingly dominated the public sphere, labeling modernist and avant-garde art as “degenerate.” Polish institutions were harassed or closed, Jewish artists were censored and exiled, and the experimental pluralism that had defined the interwar period gave way to ideological rigidity.

The invasion of Poland in September 1939, beginning with the attack on Westerplatte and the siege of the Polish Post Office, brought this fragile era to a violent end. Many artists fled, others perished, and the archives, galleries, and studios that had sustained Gdańsk’s modernist culture were destroyed or dispersed.

Still, the interwar years left an enduring legacy. The architecture, photographs, posters, and paintings of the period offer a powerful snapshot of a city at the edge—artistically fertile, politically fragile, and utterly modern. In the bold lines of a woodcut, the cool façade of a post office, or the blurred motion of a photographic negative, we glimpse the hopes and anxieties of a generation trying to imagine a future amid the ruins of empires.

War, Destruction, and the Cultural Loss of WWII

Few cities in Europe have endured cultural devastation as complete and deliberate as Gdańsk suffered during World War II. Once a vibrant port of aesthetic plurality and layered heritage, Gdańsk—then known internationally as Danzig—became both a symbol and a casualty of Nazi aggression. The war brought not only the physical destruction of buildings and objects but a systematic dismantling of identity, memory, and the fragile cohabitation that had defined the city’s cultural fabric.

The seeds of this destruction were sown in the 1930s. After the Nazis came to power in Germany, Gdańsk, still officially a Free City under the League of Nations, increasingly fell under the influence of the Third Reich. Nazi ideology began to permeate the cultural life of the city: modernist art was labeled “degenerate,” Jewish artists and intellectuals were forced into exile or silence, and Polish institutions were monitored, harassed, and gradually dismantled. Art exhibitions were censored, archives seized, and public monuments repurposed to reflect the new totalitarian aesthetic.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, the first shots were fired in Gdańsk at Westerplatte and the Polish Post Office, transforming the city overnight into a theater of war. Polish defenders were executed, and the symbolic heart of Polish identity in the city was violently crushed. This initial attack set the tone for what followed: six years of systematic cultural erasure.

As German forces consolidated control, they began the process of looting and cataloging the city’s art collections. Paintings, manuscripts, religious objects, and artifacts were seized from museums, churches, private homes, and libraries. Some were sent to Berlin or other Nazi cultural centers; others disappeared into private collections. This process was part of a broader campaign across occupied Europe: the so-called “Kunstschutz” effort that masked plunder as preservation, while in reality stripping nations of their cultural sovereignty.

Religious art—particularly Catholic and Polish-affiliated works—was targeted. Altarpieces were dismantled or burned, icons defaced, and churches stripped of their ornamentation. Jewish cultural heritage, including synagogues, libraries, and ritual objects, was completely destroyed. Gdańsk’s once-thriving Jewish population, integral to its commercial and intellectual life, was annihilated in the Holocaust. The destruction of their visual culture—family photographs, ceremonial art, architectural detail—was a chilling complement to the loss of lives.

But perhaps the most visible scar of the war came in March 1945, during the Soviet assault on the city. In the final weeks of the conflict, as Nazi forces made a last-ditch defense, the Red Army unleashed a barrage of artillery and firebombing that reduced the historic core of Gdańsk to rubble. More than 90 percent of the city’s old town was destroyed. The Main Town Hall, the Artus Court, the Golden House, the Green Gate, and hundreds of merchant homes were reduced to smoking ruins.

The St. Mary’s Church, once the pride of Gothic architecture in the Baltic region, was left a roofless shell. The magnificent interiors—wooden carvings, murals, tombstones, paintings—were incinerated or buried in debris. Entire centuries of artistic labor vanished in hours. The Neptune Fountain, blackened and cracked, stood alone in a square of ashes. Photographs from the aftermath show a cityscape that resembled Dresden, Warsaw, or Hiroshima—a place where the past had been erased not just tactically, but ideologically.

Even before the bombs fell, many cultural treasures had already been lost. In the final months of the war, the Nazi regime initiated frantic efforts to hide stolen artworks in mines, castles, and underground bunkers. Some pieces from Gdańsk were believed to have been sent to Cracow, Königsberg, or hidden in Pomeranian forests—many have never been recovered. The postwar Polish government would later establish commissions to trace these missing works, but to this day, thousands remain unaccounted for.

In the face of this devastation, an extraordinary act of cultural memory began to take shape. As Polish forces reclaimed the city in spring 1945, a new phase of Gdańsk’s history commenced—not as a continuation, but as a reconstruction. In what would become one of the largest heritage restoration projects in postwar Europe, Polish architects, historians, and artists set out to rebuild Gdańsk’s historic core from the ground up. This reconstruction was not merely architectural—it was philosophical. It asked: What is a city, if not its buildings, its images, its stories?

Using pre-war photographs, 18th- and 19th-century paintings, architectural plans, and eyewitness memories, teams of artisans recreated facades, interiors, and public artworks with astonishing fidelity. The process blurred the line between restoration and reinvention. Some buildings were rebuilt exactly as they had been; others were idealized versions, integrating historical references and nationalist symbolism. This approach, often debated among scholars, created a reconstructed Gdańsk that was simultaneously authentic and curated—a memory city, rebuilt to reaffirm cultural identity in the wake of genocide and erasure.

The artistic community in postwar Gdańsk—many of them relocated Poles from Vilnius, Lwów, and central Poland—played a crucial role in this rebirth. Painters, sculptors, and conservators brought new life to a city that had been declared dead. They painted murals, restored icons, recast statues, and slowly repopulated the emptied museums. Their work was not only restorative but creative, giving birth to a new Gdańsk aesthetic that blended memory with resilience.

Today, as one walks through Gdańsk’s Main Town, the careful reconstructions of its Baroque and Gothic buildings stand not only as architectural marvels, but as memorials. The rebuilt Neptune Fountain, the reinstalled altarpieces, the restored façades of Długi Targ—they tell a story of art as resistance, of culture as continuity. They remind us that the erasure of images is never final—that even in the face of fire and tyranny, a city’s soul can be redrawn.

And yet, there remains a quiet mourning in Gdańsk’s visual culture. The museums house fragments: charred crucifixes, scorched paintings, archival copies of works that once adorned walls now lost. The city’s cultural institutions continue to trace the fate of its missing treasures—some of which occasionally reappear in international auctions or are returned through restitution efforts.

World War II left Gdańsk with an art history marked by absence, by gaps and ghosts. But it also forged a new ethos: one in which the act of making, of recovering, of remembering—through paint, stone, and image—is itself a form of defiance.

Postwar Socialist Realism and State Control

Emerging from the devastation of World War II, Gdańsk was not only physically in ruins but also ideologically upended. The city was now firmly part of the new Polish People’s Republic, a communist state aligned with the Soviet Union. This new political reality brought a dramatic shift in how art was produced, taught, and displayed. Socialist Realism—the officially sanctioned art style across the Eastern Bloc—became the dominant visual language. Art was no longer a reflection of individual expression or historical memory, but a tool of propaganda: a carefully curated instrument of the state.

From 1949 onward, Socialist Realism became compulsory for all artists working in public view. Painters, sculptors, architects, and even graphic designers were expected to produce works that glorified the proletariat, celebrated industrialization, and reinforced communist ideology. The hero was the worker, the peasant, the engineer, often depicted with exaggerated musculature, stoic expressions, and monumental scale. Gdańsk, with its vast shipyards and rebuilding efforts, became an ideal stage for such imagery.

Murals, mosaics, and public sculptures proliferated across the city. In residential blocks, post offices, and schools, one could find idealized images of steelworkers, mothers raising children under red banners, and Leninist tableaux rendered with academic precision. The Gdańsk Shipyard in particular became a frequent subject and symbol: its cranes, welding torches, and laborers all transformed into icons of socialist rebirth. This aesthetic, while technically accomplished, was rigidly controlled by the Association of Polish Artists and Designers (ZPAP) and subject to approval by cultural ministries.

One of the key institutions shaping postwar art in Gdańsk was the State Higher School of Fine Arts (PWSSP), later renamed the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. Founded in 1945, this school trained a new generation of artists under the dual pressures of creative ambition and political compliance. While early years focused on realist drawing and monumental sculpture aligned with Party directives, many professors and students quietly sought ways to circumvent ideological constraints.

In these spaces, artistic resistance took subtle forms. Rather than overt dissent, artists embedded ambiguity and irony into their works. They played with symbolism, used allegory, or employed deliberately archaic or folkloric styles to create visual distance from the dominant narrative. A painting of a farmer might recall Polish rural traditions more than socialist productivity; a sculpture might emphasize human vulnerability rather than triumph. These quiet acts of defiance created a layered aesthetic, in which the official message coexisted uneasily with private meaning.

During the late 1950s, following the “Polish Thaw” under Władysław Gomułka, the rigid grip of Socialist Realism began to loosen. Abstract art, modernist sculpture, and experimental graphics slowly returned to galleries and studios. Gdańsk artists, many trained during the height of state control, began exploring new forms of visual language—often inspired by Western trends, albeit refracted through local conditions.

One notable figure of this period is Adam Smolana, a sculptor who remained active through multiple political regimes and whose works bridged official monumentalism with more personal expression. Similarly, artists such as Kazimierz Ostrowski and Władysław Jackiewicz brought gestural abstraction and subtle color fields into the cultural conversation, often avoiding overt politics while redefining the aesthetics of postwar Poland.

While gallery exhibitions expanded and underground salons flourished, public art continued to reflect the Party’s dominance. Monuments to communist heroes, war memorials, and murals celebrating socialist industry remained common throughout Gdańsk. However, by the 1970s, even these began to shift in tone—from triumphant to reflective, from didactic to ambiguous—mirroring the public’s growing skepticism toward the regime.

The Gdańsk Shipyard, once a beacon of socialist pride, would by the late 1970s become the epicenter of artistic and political resistance. Graphic designers and poster artists played a vital role in this shift. The rise of Solidarity (Solidarność) in 1980—an independent trade union movement born in the very shipyards once depicted in socialist murals—ushered in a new era of politicized art. Designers like Tomasz Sarnecki and others began producing posters, flyers, and leaflets that used bold typography, symbolism, and Catholic iconography to subvert the aesthetic of the regime. The famous Solidarity logo, designed by Jerzy Janiszewski, remains one of the most iconic visual statements of resistance in modern European history.

During this late period of state control, a new generation of Gdańsk-based artists emerged, pushing the boundaries of both form and content. The Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art, while formally established after 1989, grew out of the creative ferment and defiance of the 1980s, and today it houses works that trace the lineage of artistic resistance back through the decades of state repression.

One of the most poignant aspects of postwar art in Gdańsk is the way artists re-engaged with memory and loss. While the state tried to erase or reshape the past, many artists used their work to recall the city’s vanished communities, destroyed heritage, and fractured identities. Themes of absence, silence, and resilience permeated postwar exhibitions, even when couched in abstract or symbolic forms.

By the time communism collapsed in 1989, the city’s artistic identity had undergone a profound transformation. From the ruins of war and the constraints of ideology, Gdańsk’s art scene emerged not only intact, but vital—a space of negotiation, subversion, and enduring creativity.

Contemporary Art Scene and Post-Communist Revival

When the Iron Curtain fell in 1989, Gdańsk was already poised for cultural renewal. As the birthplace of the Solidarity movement, it had long served as a crucible of dissent, where art and politics were intimately entwined. The post-communist era brought new freedoms, but also new questions: how should a city with such a layered and violent history reinvent itself? How could artists honor the past while engaging with the present?

In the decades since, Gdańsk has emerged as one of Poland’s most dynamic cultural centers—home to a growing network of galleries, artist-run spaces, biennials, and experimental institutions. But the city’s art scene has never been simply about aesthetics. It continues to grapple with trauma, identity, and the ethics of remembrance.

The Rise of Independent Institutions

One of the most important developments in this period was the transformation of formerly industrial spaces into hubs for contemporary art. The Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art, founded in 1998 in a repurposed public bathhouse in the Dolne Miasto district, became a key player in fostering avant-garde and interdisciplinary work. Łaźnia offered a platform for artists working in video, installation, performance, and digital media—forms that had been marginalized or censored under the communist regime.

Exhibitions at Łaźnia often addressed themes specific to Gdańsk’s history: memory and erasure, post-industrial decay, displacement, and the tension between past and future. Artists such as Katarzyna Józefowicz, known for her intricate paper installations that resemble mental maps or fragmented manuscripts, exemplify the city’s postmodern approach to form and concept. Józefowicz’s work in particular reflects the laborious process of piecing together identity in a city that has been reconstructed in both stone and spirit.

Another key institution is the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, which underwent its own transformation after 1989. Freed from ideological constraints, the academy expanded its curriculum and embraced global contemporary trends. It became a crucible for new talent and critical theory, producing generations of artists and designers who now exhibit internationally. The Great Armoury, which houses the academy’s headquarters, symbolically bridges the city’s architectural heritage with its contemporary aspirations.

Public Art as Social Mirror

In post-communist Gdańsk, public art has taken on an increasingly vital role—not just as decoration, but as a medium for dialogue, protest, and healing. Murals, installations, and temporary interventions dot the city’s streets and waterfronts. Some commemorate the past; others challenge the present.

The European Solidarity Centre, opened in 2014 on the grounds of the former shipyard, functions both as a museum and a space for civic engagement. Its architecture—angular, rust-colored, and industrial—evokes the hulls of ships and the weight of history. Inside, exhibitions blend archival documents, immersive installations, and multimedia to narrate the history of resistance and democratization in Poland. Art here is not background—it’s foreground, part of the storytelling apparatus.

Other public artworks, like temporary light installations or interactive sculptures, engage with more ephemeral themes: migration, surveillance, climate anxiety. The Narracje Festival, launched in 2009, commissions site-specific works throughout Gdańsk’s neighborhoods. These installations often highlight marginalized histories or overlooked urban spaces, inviting residents to see their city through a different lens.

A New Generation and Global Conversations

Contemporary artists from Gdańsk today engage with both local narratives and global discourses. Artists like Dorota Nieznalska, whose controversial work interrogates religion, gender, and collective memory, push boundaries and often spark public debate. Her 2001 piece Passion, which juxtaposed Christian iconography with male anatomy, led to a widely publicized trial for “offending religious feelings”—a case that underscored the tension between artistic freedom and national identity in post-communist Poland.

Other emerging voices include Robert Kuśmirowski, known for his hyperreal reconstructions of decayed environments and obsolete technology; Honorata Martin, whose performance art often tests personal and social boundaries; and Grzegorz Klaman, a pioneer in critical spatial interventions whose works at the former shipyard address labor history, transformation, and collective trauma.

Gdańsk’s art scene also maintains strong international connections. Collaborations with German, Ukrainian, Baltic, and Scandinavian artists have helped redefine the city’s post-Cold War identity—not as a borderland of past empires, but as a transnational cultural node. Biennials, artist residencies, and EU-funded urban art initiatives have made Gdańsk a vibrant site for experimentation and exchange.

Memory, Trauma, and Identity

What distinguishes contemporary art in Gdańsk is its sustained engagement with memory. In a city that has been Polish, German, Free, and occupied—destroyed and rebuilt—memory is not abstract. It lives in walls, in street names, in cemeteries and shipyard gates. Art in Gdańsk frequently explores these layers, whether through archival work, site-specific installations, or conceptual gestures.

For many artists, especially those working in sculpture and installation, the Holocaust, postwar displacement, and the erasure of Jewish and German heritage are central concerns. Some works address these histories directly; others, like Józefowicz’s paper relics or Klaman’s interventions, evoke them indirectly—through metaphor, texture, and absence.

At the same time, the city’s younger artists are increasingly concerned with climate, gender, and digital culture. They inhabit a Gdańsk that is cosmopolitan and precarious, shaped by European integration and neoliberal transformation. Their work is less about recovering a singular identity than embracing multiplicity, contradiction, and flux.

Challenges and Continuities

Despite its vibrancy, Gdańsk’s contemporary art scene is not without challenges. Funding can be precarious, particularly for experimental or politically provocative work. Cultural policy in Poland, especially under nationalist governments, has placed pressure on institutions to align with “patriotic” values. Debates around censorship, historical revisionism, and the role of the church continue to shape the landscape.

Yet in many ways, this tension is productive. It keeps art in Gdańsk urgent, contested, and socially embedded. The city’s cultural institutions, from Łaźnia to private galleries like Kolonia Artystów, remain spaces of resistance, dialogue, and reimagining. Artists are not simply decorating the post-communist city—they are co-authoring its identity.

As Gdańsk moves deeper into the 21st century, its contemporary art continues to oscillate between memory and futurity, between global aesthetics and local commitments. Whether through a paper installation, a performance on a former battleground, or a mural on a crumbling wall, Gdańsk’s artists are building a visual language that reflects not only where the city has been—but where it might yet go.

Public Art, Murals, and Heritage Today

In the post-communist era, Gdańsk has emerged not only as a center of historical memory but as a city where public art plays an increasingly visible and meaningful role. Across squares, building facades, waterfronts, and repurposed industrial spaces, public art contributes to the identity of a city continually shaped by its long and complex history. These works—ranging from monumental sculptures to modern murals—offer a visible bridge between the past and the present, enriching the urban landscape and inviting reflection.

A Tradition of Monumental Public Art

Gdańsk’s tradition of public sculpture dates back centuries, from the Neptune Fountain to the richly decorated façades of merchant houses. This tradition continued in the 20th century, particularly with works like the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970, erected in 1980. The monument’s massive steel crosses, installed near the shipyard gates, commemorate those who lost their lives during protests against the communist government. Beyond its historical importance, it remains one of the city’s most powerful and enduring public artworks.

Numerous postwar monuments across Gdańsk serve as tributes to national memory, historic milestones, and local figures. These include memorials to World War II victims, military leaders, and cultural icons. Such works maintain a strong presence in civic life and often accompany official commemorations or educational efforts.

Murals and Urban Aesthetics

In recent decades, Gdańsk has seen the rise of large-scale murals, particularly in residential areas such as the Zaspa district. Beginning in the 1990s and growing through local cultural initiatives, Zaspa has become one of the largest outdoor mural galleries in Europe. Many of these works were created by artists from Poland and abroad, often illustrating themes from Gdańsk’s history, maritime culture, and civic life.

These murals have enhanced the visual character of the district and created opportunities for educational and community engagement. They’re typically apolitical in tone and emphasize storytelling, identity, and beautification of the urban environment. The murals, coordinated through guided tours and local programming, reflect the city’s commitment to making art accessible beyond traditional institutions.

Restoration and Heritage in the Public Eye

Following the city’s near-total destruction in World War II, much of Gdańsk’s current public art exists in the context of architectural and sculptural restoration. The reconstruction of the Old Town, a decades-long effort undertaken by Polish conservators, restored historic buildings, portals, and decorative features based on archival materials. As a result, many of the city’s current public artworks—including Gothic and Renaissance-style reliefs—are reconstructions that have become iconic features of the cityscape.

Efforts continue to preserve and integrate historical motifs in new developments. Whether through bronze commemorative plaques, bas-reliefs, or stylized street furniture, Gdańsk balances modernization with respect for traditional craft and form. Architects and planners often work alongside artists and historians to maintain visual harmony within the historical zones.

Contemporary Installations and Cultural Infrastructure

In addition to monuments and murals, contemporary public art installations occasionally appear through local cultural institutions or city-sponsored festivals. These installations are typically temporary, aesthetically driven, and focused on engaging a broad public. Lighting projections, site-specific sculptures, and architectural interventions appear in places like Granary Island, Targ Węglowy, and along the Motława waterfront, particularly during cultural events and holidays.

The city also supports contemporary art through institutions like the Łaźnia Centre for Contemporary Art, which, while not strictly a public space, often commissions or facilitates works that interact with the broader urban environment. Similarly, the European Solidarity Centre, aside from its museum function, maintains public spaces and architectural elements that honor historical memory through contemporary design.

A City in Conversation with Its Past

Throughout Gdańsk, public art functions as a reflection of the city’s character: layered, respectful of history, and outward-looking. Rather than imposing a singular narrative, these works invite exploration and recognition of Gdańsk’s role as a historic Baltic port, a site of resilience and reconstruction, and a vibrant urban center.

Public art in Gdańsk today is neither overtly politicized nor narrowly decorative. It serves a variety of purposes: commemoration, education, urban enhancement, and cultural continuity. Whether through a traditional monument, a colorful mural, or a restored architectural detail, these works contribute to a shared visual language that helps define what Gdańsk is—and what it continues to become.