Long before the chant of Buddhist monks echoed through the high plateaus and valleys of Tibet, the region bore witness to a rich spiritual and visual culture rooted in what is now known as the Bon tradition. Often misunderstood or reduced to a mere precursor of Buddhism, Bon is in fact a complex and enduring belief system with its own pantheon, rituals, and artistic expressions. To understand Tibetan art history, we must first journey into the depths of this pre-Buddhist world—where animism, shamanism, and early religious iconography coalesced into a distinct visual language.

A Land of Spirits and Stones

Tibet’s vast and rugged terrain—its mountains, rivers, and windswept plains—was perceived as alive with spiritual power. Early inhabitants carved and painted symbols onto rocks, caves, and cliff faces, invoking protective deities or marking sacred landscapes. These petroglyphs, found across the Tibetan Plateau and often dated to as early as the 2nd millennium BCE, are among the oldest known artistic expressions in the region. Common motifs include hunters, yaks, chariots, and solar symbols—traces of a people whose spiritual life was interwoven with the natural world.

These rock carvings, while not unique to Tibet, exhibit stylistic traits that hint at both local invention and broader Central Asian exchanges. Some show similarities to Scythian and Steppe art, suggesting nomadic influence, while others reflect unique local mythologies. The images are not merely decorative: they functioned as talismans, markers of territory, or ritual objects in their own right.

The Bon Religion: Cosmos, Ritual, and Vision

The Bon tradition, which crystallized into an organized religious system around the 8th–9th centuries CE but claims far older roots, offers a rich framework for understanding Tibet’s early spiritual art. Bon posits a cosmos populated by myriad spirits—both benevolent and malevolent—that must be appeased through ritual. Practitioners engaged in elaborate ceremonies involving chants, dance, and the crafting of ritual objects, many of which left behind a tangible artistic legacy.

One of Bon’s most distinctive visual contributions is the use of ritual effigies and symbolic diagrams, often drawn with sand or pigments during ceremonies. These early forms prefigure the Buddhist mandala, yet differ in their orientation and purpose—focusing more on harmonizing elemental forces than mapping enlightened realms.

Objects such as tsa tsa (miniature votive tablets made from clay) and ritual knives (phurba) appear in Bon contexts, often inscribed with invocations or adorned with fierce imagery designed to repel harmful entities. These items blend aesthetics with magical function—a hallmark of much of Tibetan art.

Sacred Geography and the Visual Language of Power

Bon’s emphasis on sacred geography also had a significant visual impact. Certain mountains—such as Mount Kailash—were considered the abodes of deities and were represented in stylized, symbolic forms. Unlike the realistic landscapes of Chinese painting, Tibetan depictions of sacred geography were diagrammatic, meant to encode metaphysical truths rather than depict physical terrain. This approach laid the groundwork for later Buddhist art, which would inherit and refine this abstracted spatial logic.

Bon rituals also made use of sky-burial sites, altars, and cairns, often marked with carved stones or painted banners. While perishable materials rarely survive, these ephemeral constructions hint at a highly visual, performative culture where art was inseparable from ritual action.

Intersections and Tensions with Buddhism

By the time Buddhism began to spread in Tibet in the 7th century CE, Bon had already established a strong presence. The two systems would come into both conflict and dialogue. Buddhist accounts often portrayed Bon as demonic or misguided, a narrative strategy aimed at legitimizing the new orthodoxy. Yet in practice, the two traditions exchanged ideas and iconography. Many early Buddhist images bear Bon influences, particularly in the representation of wrathful deities, protective rituals, and the integration of indigenous symbols like snow lions and flaming jewels.

Even today, Bon continues as a living tradition, with its own monasteries, art styles, and canon. Artists from Bon lineages still produce thangkas, sculptures, and ritual items that reflect a worldview parallel to, but distinct from, mainstream Tibetan Buddhism.

Conclusion: A Hidden Foundation

Though often overshadowed by the grandeur of Tibetan Buddhist art, the pre-Buddhist artistic heritage of Tibet deserves recognition not only as a foundation but as a living thread in the cultural fabric of the region. From ancient petroglyphs to Bon rituals rich in color and form, this early art reveals a Tibet that was already deeply engaged in the visual expression of the sacred long before the arrival of the Buddha’s teachings.

In many ways, understanding Bon and pre-Buddhist art opens a portal into the Tibetan imagination—one where mountains speak, wind carries messages from the spirits, and every stone might hold a deity’s presence. It’s a vision that continues to animate Tibetan aesthetics even in the most refined Buddhist works.

The Arrival of Buddhism and the Yarlung Dynasty (7th–9th Century)

The 7th century marked a seismic shift in the spiritual and artistic life of Tibet. With the rise of the Yarlung Dynasty and the introduction of Buddhism under King Songtsen Gampo, Tibet transitioned from a world of indigenous deities and animistic rituals into a newly Buddhist society. This transformation was not immediate nor uncontested—it was gradual, complex, and deeply syncretic. As new ideas took root, they found expression in the visual arts, resulting in a hybrid style that would shape Tibetan aesthetics for centuries to come.

The Yarlung Dynasty and Statecraft

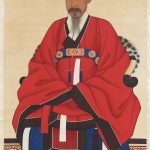

At the heart of this transformation was Songtsen Gampo (c. 605–649 CE), a powerful unifier and the 33rd king of the Yarlung lineage. From his seat in the Yarlung Valley, he consolidated rival clans, built an imperial state, and established Lhasa as a cultural and political center. Crucially, Songtsen Gampo also adopted Buddhism—reportedly under the influence of his two foreign wives, Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal and Princess Wencheng of China—each of whom is traditionally credited with bringing Buddhist scriptures, images, and artisans into Tibet.

Whether these marriage alliances were acts of devotion or political strategy (likely both), they had enormous cultural consequences. The foreign princesses are said to have brought statues of the Buddha—most famously, the Jowo Rinpoche in Lhasa—and helped construct the earliest temples in the land, including the Jokhang and Ramoche temples. These structures were not just religious sites—they were architectural symbols of a new cultural horizon.

Architectural Fusion: The Birth of Tibetan Buddhist Spaces

The construction of the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa stands as a defining moment in the visual history of Tibet. Built around 652 CE, the Jokhang integrated Nepalese craftsmanship (thanks to Bhrikuti), Chinese aesthetics (via Wencheng), and indigenous Tibetan spatial sensibilities. The result was an architectural style unique to Tibet—an early synthesis that would evolve but never lose its tri-cultural roots.

Inside the Jokhang, early murals and statuary reflected the Pala-style of northeast India and the Newar style of Nepal. These artworks are delicate, idealized, and richly adorned—far from the fierce iconography that would later become synonymous with Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. At this stage, the art emphasized the peaceful Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, symbols of compassion and wisdom, rather than the wrathful guardians that came later.

Yet these early Buddhist temples were not imposed on a blank slate. They often absorbed or displaced older Bon and animistic traditions. In some cases, pre-existing sacred sites were converted, layered over with new meanings and images. Even the Jokhang was reportedly built atop a lake that was said to represent a supine demoness—one of several “earth demons” subdued by the placement of Buddhist temples on her body. This myth reveals how Buddhist art in Tibet initially framed itself not in opposition to indigenous beliefs, but as a force of cosmic harmonization.

The Role of Imported Artisans

Much of Tibet’s early Buddhist art was created not by Tibetans, but by artisans from Nepal and India. The Newar craftsmen, in particular, played a central role in designing temple interiors, casting bronzes, and painting murals. Their techniques—marked by finely detailed figures, elaborate ornamentation, and idealized bodily forms—set the stylistic template for Tibetan Buddhist art.

Indian influence came primarily from the Gupta and post-Gupta traditions of northern India, especially the Pala Empire in Bengal. These influences introduced the symmetrical compositions, soft modeling, and iconographic precision that would become standard in Tibetan Buddhist imagery.

Despite their foreign origins, these styles were not simply copied. They were selectively adapted to Tibetan religious needs, local tastes, and climatic conditions. Over time, this led to the emergence of a distinctly Tibetan visual vocabulary, though one still deeply indebted to its multicultural roots.

Translation and Transmission

Art was not the only vehicle for Buddhist transmission. During the Yarlung period, Tibet began its immense translation project—rendering Buddhist texts from Sanskrit and Chinese into Tibetan. This effort, spearheaded by Indian scholars and Tibetan translators working side by side, helped codify both the religion and its iconography.

As new philosophical schools arrived—Madhyamaka, Yogacara, and later Tantric traditions—they brought new deities, ritual tools, and cosmologies that artists were tasked with depicting. This began the long Tibetan tradition of combining visual precision with doctrinal accuracy. Every image—whether a thangka, mural, or statue—was not merely art but a theological diagram, reflecting specific texts, meditation practices, and initiatory lineages.

Resistance and the Langdarma Backlash

Not everyone welcomed the rise of Buddhism. King Langdarma, who ruled in the late 9th century, reportedly rejected Buddhist teachings and initiated a persecution of monks and destruction of temples. While the historical record is patchy, his reign marked a rupture in institutional Buddhism and the collapse of the centralized Yarlung dynasty.

This period of suppression fragmented the Buddhist establishment, sending teachers, monks, and artisans into remote regions. Ironically, this dispersal may have helped seed Buddhist art more widely across Tibet, as small monasteries and local patrons kept traditions alive in exile. It also paved the way for the “Second Dissemination” of Buddhism, which would come with renewed artistic vigor in the centuries ahead.

Conclusion: The Foundations Are Laid

The Yarlung Dynasty did not invent Tibetan Buddhist art, but it laid its foundations. Through temple construction, the importation of sacred images and artisans, and the sponsorship of translation projects, Songtsen Gampo and his successors forged a visual and spiritual infrastructure that would define Tibet for the next millennium.

In this era, we see the first glimmers of the Tibetan genius for synthesis—an ability to absorb and transform diverse influences into a coherent, spiritually resonant aesthetic. This capacity would become the hallmark of Tibetan art: a form that is always rooted in tradition, but never static.

The “Second Dissemination” and the Rise of Monastic Art (10th–12th Century)

Following the collapse of the Yarlung Dynasty in the late 9th century and the reported anti-Buddhist persecution under King Langdarma, Tibet entered a period of fragmentation and political decentralization. Yet rather than spell the end of Buddhism, this so-called “dark age” set the stage for one of the most important phases in Tibetan art and religious history: the Second Dissemination of Buddhism. Beginning in the 10th century, this cultural revival brought with it a renewed wave of artistic creativity—marked by the foundation of new monasteries, the rise of regional schools, and the full integration of Vajrayana imagery into Tibetan visual culture.

A Revival from the Grassroots

The Second Dissemination (also called phyi dar, or “later spread”) was not driven by imperial power, as the first had been. Instead, it grew from local dynasties and regional patrons, many of whom sought to legitimize their rule through religious sponsorship. As Tibetan aristocrats and clans vied for influence, patronage of Buddhist monks and monasteries became a key strategy. This shift from royal to decentralized support created a rich mosaic of regional artistic styles and religious institutions.

One of the key catalysts of this revival was the pilgrimage of Tibetan monks to India, particularly to the great centers of Buddhist learning like Vikramashila and Nalanda. Figures such as Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055), known as the “Great Translator,” studied abroad and returned with texts, images, and foreign artisans. Rinchen Zangpo is credited with founding or renovating over a hundred monasteries, including the famed Toling Monastery in western Tibet, which became a crucible for early monastic mural painting.

Mural Painting Comes Into Its Own

During this period, mural painting became a dominant form of monastic art. While early Buddhist temples such as Jokhang had already featured wall paintings, it was in the 10th to 12th centuries that murals evolved into grand narrative cycles and complex cosmological diagrams. These paintings served both didactic and devotional purposes—educating monks and lay visitors about the Buddha’s life, the Jataka tales (stories of the Buddha’s previous lives), and tantric deities.

The walls of monasteries such as Toling, Tabo (in nearby Ladakh), and later Alchi (in modern-day India) reveal a sophisticated visual language. Artists used mineral pigments on dry plaster, creating vibrant and durable images in deep reds, blues, golds, and earthy browns. These works reflect a continued debt to Pala and Kashmiri styles—evident in the smooth modeling of figures, elaborate jewelry, and delicate expressions—but they also show the emergence of a more robust, localized aesthetic. Bodies become more solid, colors deeper, and the overall composition more crowded and intense.

The Rise of Monasteries as Art Centers

As Buddhism re-established itself, monasteries became not only centers of ritual and learning but also hubs of artistic production. Monks and lay artisans collaborated in the creation of sculptures, paintings, manuscripts, and ritual implements. The monastery became a total art environment—its very architecture serving as a mandala, its interiors a visual map of the Buddhist cosmos.

New monastic foundations like Sakya, Samye (rebuilt during this period), and Phugtal in remote caves became spiritual and artistic strongholds. These spaces hosted increasingly complex forms of Vajrayana Buddhism, which emphasized esoteric practices, deity yoga, and ritual empowerment. Art needed to reflect these developments, and so iconography became more precise, standardized, and layered with meaning.

Images of wrathful deities—Mahakala, Yamantaka, and Vajrakilaya—grew more common, their ferocity symbolizing the destruction of ego and ignorance. Intricate mandalas, previously sketched in sand or on cloth, were now painted on walls or cast in metal, serving as meditative diagrams and ritual tools. Every element, from the number of arms on a deity to the color of its body, was laden with symbolism and doctrinal precision.

The Influence of the Kadam School

Among the many schools that emerged during this period, the Kadam tradition had a particularly strong impact on monastic art. Founded by Atisha (982–1054), a Bengali monk invited to Tibet in the 11th century, the Kadam school emphasized ethical conduct, gradual path teachings, and the proper transmission of texts and iconography.

Kadam monasteries focused on creating clear, orderly, and devotional imagery. Their thangkas and murals often depicted lineage trees, where the founder Atisha was shown seated below the Buddha, surrounded by a chain of teachers. These lineage paintings were vital in maintaining authenticity and were often used as visual aids in oral instruction.

Although the Kadam school would eventually merge into the later Gelug tradition, its contributions during the Second Dissemination helped establish a visual lexicon for depicting teachers, teachings, and ethical ideals—a lexicon that persists across Tibetan art.

Artisan Networks and Transmission of Style

This was also a time of growing mobility for artists. Nepalese and Kashmiri craftsmen continued to travel into western and central Tibet, bringing with them metalworking techniques and iconographic models. At the same time, local Tibetan artisans began to develop their own signatures, creating regionally distinctive styles in areas like Guge, Ladakh, and Tsang.

It’s during this period that the characteristic Tibetan bronze style emerges—gilded copper statues with inlaid jewels, finely chased patterns, and robust, balanced forms. These images, while indebted to Newar and Pala models, show increasing independence and innovation. The “Tibetanization” of Buddhist art was underway.

Conclusion: A New Artistic Identity Takes Shape

The Second Dissemination was a time of renewal, reinvention, and the consolidation of a Tibetan Buddhist visual identity. What had once been imported—texts, teachers, and art styles—was now internalized and transformed into something distinctly Tibetan. Monasteries emerged not only as spiritual centers but as engines of artistic production, where the sacred was made visible through pigments, metal, and stone.

In these centuries, we begin to see the full flowering of Tibetan art as a visual theology—a system where every line, color, and gesture corresponds to a layer of doctrine or a stage on the path to enlightenment. The groundwork laid here would support the spectacular developments of the later Sakya, Kagyu, and Nyingma traditions, all of which took root during or soon after this artistic rebirth.

Pala Influence and Indian Tantric Aesthetics in Tibetan Art

To understand the trajectory of Tibetan art in the medieval period, one must look south—to the verdant plains of eastern India, where the Pala Empire (c. 8th–12th centuries) flourished as a bastion of Buddhist thought and visual culture. The Pala dynasty was not only a political power but also a spiritual beacon. Its monastic universities—most notably Nalanda, Vikramashila, and Odantapuri—were vibrant centers of Tantric Buddhism and the arts. For Tibet, the Pala world was both an inspiration and a resource, providing the templates, teachers, and techniques that would shape its religious art for centuries to come.

The Pala Aesthetic: Grace, Geometry, and Devotion

The Pala style, as it is now known, was characterized by sensuous lines, delicate ornamentation, and an emphasis on grace and symmetry. Sculptures in bronze and stone from this period often depict Buddhas and Bodhisattvas seated in balanced meditative postures, their limbs soft and fluid, their expressions serene but inwardly intense.

These images were never merely decorative. They were theological statements, designed in accordance with precise iconographic treatises like the Sadhanamala, which prescribed dimensions, attributes, and postures based on spiritual function. A Pala Buddha, for instance, was less a portrait than a metaphysical diagram—a crystallization of enlightenment in physical form.

Tibetan monks and artists who traveled to India absorbed this visual language deeply. The symmetry, iconographic clarity, and rich but restrained ornamentation of Pala art would become cornerstones of early Tibetan Buddhist sculpture and painting.

Transmission of Art Through Translation and Travel

The movement of Pala influence into Tibet was not abstract—it was carried by people. Key figures like Atisha (982–1054), a renowned Pala monk and scholar from Vikramashila, played pivotal roles in transmitting both doctrine and visual tradition. Atisha’s journey to Tibet in the 11th century (invited by western Tibetan king Yeshe-Ö) sparked a wave of translation activity that included not just texts but visual knowledge. His followers, especially the Kadam school, emphasized precise iconography as a tool for spiritual instruction.

In addition to monks, artists and craftsmen from Bengal and Bihar traveled north, bringing Pala aesthetics to the Himalayan frontier. Simultaneously, Tibetan patrons and translators returned from pilgrimages to Indian monasteries with illustrated manuscripts, bronze icons, and sketches—items that served as visual templates for Tibetan creators.

These objects were not simply copied; they were internalized and recontextualized. Over time, the Pala idiom blended with Nepalese intricacy and Tibetan solidity, forming the triadic base of Tibetan Buddhist art.

Tantric Imagery and Its Visual Implications

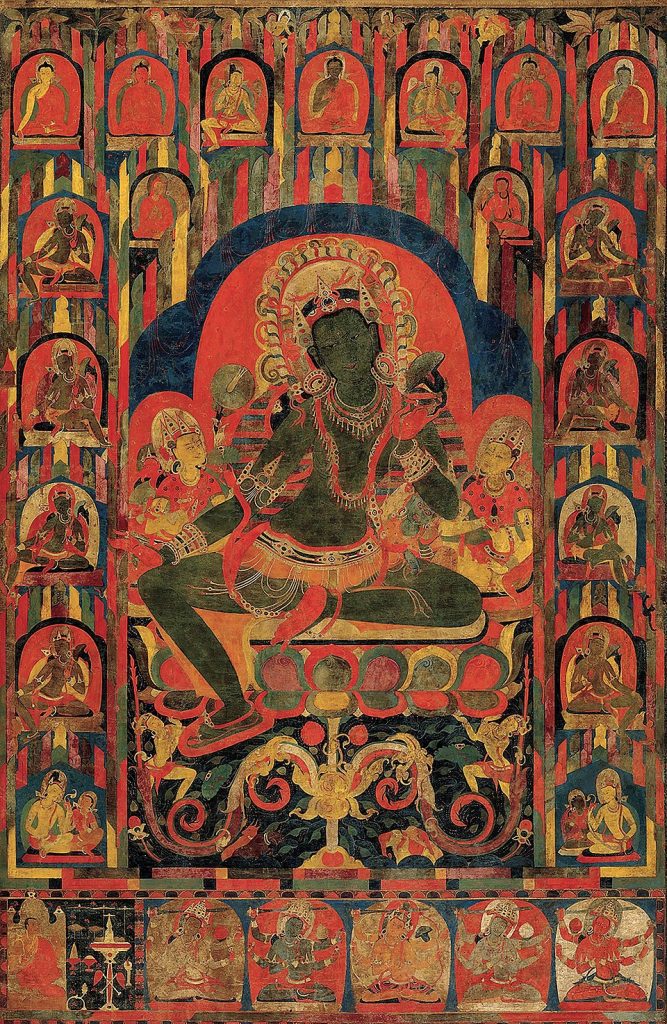

Perhaps the most transformative aspect of the Pala legacy in Tibet was the introduction and normalization of Tantric (Vajrayana) iconography. While Mahayana images—Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in meditative stillness—were already part of Tibetan art, the Pala-influenced Tantric deities introduced a radically different energy.

These deities were not serene teachers but fierce protectors, cosmic lovers, or wrathful manifestations of wisdom. Figures like Hevajra, Chakrasamvara, Vajrayogini, and Heruka—many with multiple heads, arms, or in ecstatic union (yab-yum)—now entered the Tibetan visual world. Each of these figures had ritual functions and was often tied to initiation ceremonies (abhisheka) and esoteric meditation practices.

Artistically, this required new visual strategies. Compositions became more dynamic and crowded; deities bore complex attributes like skull bowls, flaying knives, and ritual scepters; backdrops flamed with halos and auras of spiritual energy. The shift from the placid Mahayana imagery to these dramatic, often terrifying forms marked a new phase in Tibetan aesthetics: one that embraced visual intensity as a path to spiritual transformation.

The Tension Between Tantric Secrecy and Artistic Publicness

One challenge that accompanied Tantric imagery was the tension between its esoteric nature and its increasing visual prominence. In theory, many of the deities and rituals associated with Tantric Buddhism were secret—accessible only to initiates under qualified teachers. Yet artists had to depict them for temples, murals, and thangkas.

This created a kind of coded visual language: symbolic gestures (mudras), hand-held objects (such as vajras and bells), and color schemes denoted not just identity but also spiritual function and level of practice. For example, a blue Chakrasamvara in union with red Vajravarahi is not just a mythic tableau—it is a representation of method and wisdom, the union of compassion and insight.

For Tibetan practitioners, these images were tools—mental mirrors used in visualization practices, not just devotional icons. Their complexity served a purpose: to train the mind to hold multiple levels of meaning simultaneously, to see beyond surface form into spiritual essence.

Legacy in Sculpture and Painting

The influence of Pala aesthetics remained most visible in sculpture well into the 13th and 14th centuries. Early Tibetan bronze images, often created by Newar or Kashmiri artisans under Tibetan patronage, exhibit the fluid elegance of the Pala style—slender torsos, serene faces, and precise, balanced forms.

In painting, the Pala influence shows in the symmetry of composition, use of sacred geometry, and dense iconographic layering. Tibetan manuscript illuminations from this period, though rare, also echo Indian prototypes in their color palette and narrative clarity.

Even as Tibetan art would later evolve its own bolder, more muscular forms (especially under Sakya and Kagyu influence), the Pala foundation never disappeared. It provided the artistic grammar that made Tibetan Vajrayana art legible, coherent, and spiritually potent.

Conclusion: The Indian Imprint

The Pala contribution to Tibetan art is immeasurable. It was not simply an external influence but a foundational inheritance—offering both aesthetic models and theological frameworks that helped Tibet construct its own visual language. Through the transmission of Tantric imagery, iconographic treatises, and master artisanship, the Pala world gave Tibet the tools to translate the invisible into the visible.

Yet Tibet did not remain a passive recipient. It reimagined, restructured, and in time, surpassed its Indian teachers—creating an art that was uniquely its own, even as it bore the fingerprints of Nalanda and Vikramashila.

The Tibetan Thanka: Development, Symbolism, and Technique

Few art forms capture the spiritual and aesthetic complexity of Tibet as powerfully as the thangka—a sacred scroll painting designed for meditation, ritual use, and teaching. Suspended between painting and performance, object and image, thangkas are not merely decorative artifacts. They are visual texts, rich with encoded meaning, designed to guide the mind through the intricate topography of Tibetan Buddhism. Over centuries, the thangka evolved into a uniquely Tibetan form, combining influences from India, Nepal, and China with local innovation, devotional intensity, and artistic discipline.

Origins: From Portable Icons to Sacred Scrolls

The word thangka (also spelled tangka or thankha) is derived from the Tibetan term thang yig, meaning “recorded message” or “something that can be rolled up.” This etymology reflects the thangka’s original function: a portable devotional image. In early Tibetan monasteries, where itinerant teachers traveled between isolated communities, thangkas served as foldable altarpieces—easy to transport, hang, and display in temporary shrines.

The form likely originated from Indian palm-leaf manuscripts and illustrated ritual diagrams (yantras), which were brought into Tibet during the early dissemination of Buddhism. These textual and pictorial hybrids slowly evolved into full-scale paintings on cloth. Nepalese and Kashmiri artisans introduced techniques for pigment mixing and silk mounting, while the Buddhist need for iconographic clarity and reproducibility helped solidify the thangka as a standardized format.

By the 12th century, thangkas had become a central feature of Tibetan religious life—used in initiation rituals, daily prayer, meditation, festivals, and even political diplomacy.

Structure and Materials: A Confluence of Art and Engineering

A thangka is both fragile and resilient. It is typically painted on cotton or silk canvas, prepared with a layer of gesso made from animal glue and ground white stone (often chalk or limestone). This surface is then polished smooth and stretched taut on a wooden frame. The composition is drawn using charcoal or red pigment, then carefully painted with mineral-based colors—azurite for blue, malachite for green, cinnabar for red, orpiment for yellow, and sometimes gold leaf or powdered gold for highlights.

Once completed, the painting is mounted in an elaborate silk brocade frame, with a wooden dowel at the bottom for rolling. The brocade is more than aesthetic—it protects the painting, signifies its ritual importance, and allows the thangka to be carried, displayed, and stored with reverence.

A key aspect of thangka production is its adherence to geometric proportion. Artists followed strict iconometric manuals (such as the Chitra Sutra or the Sangwa Düpa) that dictated the measurements of deities, hand gestures (mudras), poses (asanas), and even the layout of secondary figures. This wasn’t artistic constraint—it was a spiritual necessity. A poorly proportioned Buddha, by traditional understanding, would be metaphysically incorrect and unsuitable for practice.

Types and Themes: A Visual Cosmos

Thangkas vary widely in theme, function, and composition. Some focus on a single deity, such as Shakyamuni Buddha, Avalokiteshvara, or Tara, portrayed in a frontal meditative pose surrounded by halos of light. Others are highly narrative, depicting the life of the Buddha, the Eight Great Events, or the legendary exploits of Tibetan saints like Milarepa or Padmasambhava.

Another major category includes mandala thangkas—cosmic diagrams centered on a deity’s palace, surrounded by guardians, consorts, and symbolic elements. These serve as visual maps for tantric initiation and meditation, aiding practitioners in mentally constructing the deity’s realm and identifying with the enlightened presence.

Thangkas also include lineage trees, which trace the transmission of teachings from primordial Buddhas to living masters, often with hundreds of figures organized around a central guru. Others are astrological charts, medical illustrations, or protective deities used in exorcistic rituals. In all cases, the function of the thangka determines its content and style.

Symbolism and Visual Pedagogy

Thangkas are designed to communicate multi-layered meaning at a glance. A skilled practitioner can “read” a thangka much like a scholar reads a sutra. Every element—gesture, color, posture, surrounding figure—communicates something doctrinal.

- Color is not merely decorative: white symbolizes pacification, red magnetism, green accomplishment, blue destruction, and yellow increase.

- Attributes such as a vajra (diamond scepter), lotus, or skull bowl signify the deity’s role or family within the tantric pantheon.

- Posture can indicate meditative stillness (lotus posture), wrathful energy (one leg extended), or dynamic dance (tribhanga pose).

This symbolic density allows thangkas to operate on multiple levels. To the uninitiated, they may appear as beautiful religious paintings. To a trained practitioner, they are instruction manuals for deity yoga, visual invocations of sacred presence, and mnemonic devices for entire cycles of teaching.

Artistic Lineages and Regional Schools

Over time, distinct styles of thangka painting emerged across Tibet and neighboring regions. The three most prominent are:

- Menri (སྨན་རིས་): Developed in the 15th century under Khyentse Chenmo, this style is known for its elegant clarity, jewel-like colors, and refined outlines. It became the “official” Gelug school style and was widely taught in monastic art schools.

- Karma Gardri (ཀརྨ་མགོ་བྲིས་): A looser, more expressive style linked to the Karma Kagyu tradition, emphasizing landscape, atmospheric depth, and a more Chinese-inflected visual space.

- Newar and Bhutanese styles: Drawing heavily from Nepalese craftsmanship, these thangkas are more intricate and decorative, often featuring densely packed compositions and meticulous detailing.

These styles coexisted and cross-pollinated, depending on region, patron, and religious school. Even within a single monastery, different thangkas might reflect different lineages or historical periods.

Ritual Use and Sacred Status

A thangka is not finished when the last brushstroke is laid. It must be consecrated—usually by a lama who blesses it, installs mantras in its back, and “opens the eyes” of the central deity in a short ritual. Only then is the painting considered alive, worthy of veneration, and ritually effective.

Thangkas are not hung permanently. They are unrolled for ceremonies, displayed on feast days, carried in procession, or meditated upon during retreats. Giant thangkas—sometimes several stories tall—are displayed on monastery walls during festivals like the annual Tibetan New Year (Losar) or Monlam Chenmo, turning the landscape itself into a canvas of devotion.

Because of their ritual role, thangkas are treated with deep respect. They are stored carefully, handled only by trained individuals, and in some traditions, even whispered to as if alive.

Conclusion: A Devotional Masterwork

The Tibetan thangka is an exquisite paradox: fixed in form, yet endlessly varied; rigid in geometry, yet emotionally powerful; ephemeral in display, yet enduring in cultural memory. It is a testament to the Tibetan ability to weave art and spirituality into a single inseparable fabric.

More than any other medium, thangkas capture the heart of Tibetan visual philosophy: that images are not distractions from the spiritual path, but vehicles for awakening itself. To gaze upon a thangka is, in a real sense, to begin the work of transformation.

Mandala Art: Sacred Geometry and Ritual Usage

In the lexicon of Tibetan Buddhist art, few forms are as intellectually rich, spiritually potent, and visually mesmerizing as the mandala. At once a geometric diagram, a meditative aid, and a ritual arena, the mandala is a profound expression of how Tibetan Buddhism maps the cosmos—both external and internal. While mandalas are often thought of as paintings or sand constructions, they are more than that. They are three-dimensional visions rendered into two-dimensional space, blueprints of divine realms, and instruments for profound psychological and spiritual transformation.

To study the mandala is not simply to explore an artistic tradition—it is to engage with a vision of the universe in perfect harmony, where form and emptiness, deity and devotee, space and consciousness, collapse into one.

Origins: From Vedic Altars to Tantric Palaces

The concept of the mandala (dkyil ‘khor in Tibetan, meaning “center and periphery”) predates Buddhism. It likely originated in Vedic fire rituals, where altars were carefully measured and constructed as cosmic diagrams. As Buddhism developed, especially in its tantric forms, the mandala evolved from a physical altar into a visual representation of a sacred universe.

In India, especially during the Pala period, mandalas became central to tantric ritual practice. They represented the residence of a central deity (often a Buddha or Bodhisattva in his wrathful or blissful form) surrounded by retinues, guardians, and symbols. These visualizations were essential to deity yoga, the process by which a practitioner identifies with a deity to realize their enlightened qualities.

When tantric Buddhism entered Tibet in the 8th–10th centuries, the mandala was already a sophisticated ritual and artistic system. Tibetan artists, monastics, and yogis refined and expanded it, integrating it into temple architecture, sand art, mural painting, and portable thangkas.

Structure and Symbolism: Reading the Mandala

A traditional Tibetan mandala is an expression of sacred geometry. Though thousands of variations exist, most follow a shared conceptual and visual framework:

- The Outer Circle: Often composed of flames (symbolizing protection), vajras (representing indestructibility), or lotus petals (indicating purity), this perimeter defines the spiritual space, separating the sacred from the mundane.

- The Square Palace: At the heart of the mandala lies a multi-gated palace, each gate aligned to a cardinal direction. The palace symbolizes the mind of the deity and is divided into chambers that correspond to stages of initiation or levels of consciousness.

- The Central Deity: Seated at the innermost point is the main figure—such as Chakrasamvara, Vajrayogini, or Kalachakra—often in union with a consort. This pairing symbolizes the unity of wisdom (female) and compassion or method (male).

- The Retinue: Surrounding the central deity are often four or more subsidiary figures, each with symbolic color, mudra, posture, and weapon. These may include directional guardians, wrathful emanations, or aspects of the central deity’s mind.

The entire composition is imbued with numerological and astrological meaning. Colors, shapes, and spatial relationships are not decorative—they embody metaphysical truths. For instance, a square within a circle reflects the union of earth and heaven; a multi-armed deity represents manifold compassionate activity.

Materials and Mediums: Painting, Sand, and Architecture

Mandalas are executed in various media, each with distinct functions and contexts:

- Painted Mandalas: Found in thangkas and murals, these are used for daily meditation, initiatory teachings, and visualization practices. They are often commissioned for specific rituals and consecrated by a lama.

- Sand Mandalas: Perhaps the most dramatic form, sand mandalas are created grain-by-grain using colored sand and metal funnels (chak-pur). The process can take days or weeks and is performed by teams of monks with extraordinary precision. Upon completion, the sand mandala is ritually dismantled—its beauty offered back to the cosmos, reinforcing the Buddhist teaching of impermanence (anicca).

- Architectural Mandalas: Entire temples and monasteries, such as Samye Monastery, are constructed as three-dimensional mandalas. These are walkable sacred spaces, where pilgrims circumambulate layers of meaning. The inner sanctum may be reserved for initiated monks, just as the center of a painted mandala is conceptually the most esoteric.

- Thread Cross Mandalas (Namkha): Found in Bon and early Tibetan traditions, these are symbolic cosmic diagrams made of colored threads and sticks, used in rituals to harmonize elemental forces.

Ritual Usage: Transformation Through Visualization

In Vajrayana Buddhism, the mandala is not just a map—it is an engine for transformation. During tantric initiations (abhisheka), the disciple is symbolically invited into the mandala, visualized as entering the deity’s palace, and merging with the central figure. In doing so, they are ritually reborn with a purified identity.

Meditation on mandalas involves visualizing the diagram in great detail, building it mentally from the outside in, populating it with deities, and ultimately merging with the enlightened mind it represents. This is a profoundly disciplined practice, often requiring years of instruction and initiation.

For monastics and advanced practitioners, mandalas are also used in sadhanas (daily tantric rituals), empowerments, and fire pujas, each with precise iconographic requirements.

Cultural and Artistic Impact

The mandala influenced not only painting but also metalwork, textiles, manuscript illumination, and even landscape design. The spatial logic of mandalas shaped how Tibetans thought about sacred geography—mountains, temples, and pilgrimage routes were often imagined in mandalic terms.

Over time, specific mandalas became emblematic of lineages or schools:

- The Kalachakra Mandala, linked to the Jonang and Gelug traditions, is a supremely complex structure that includes cosmology, astrology, and esoteric anatomy.

- The Chakrasamvara Mandala, used by the Kagyu school, emphasizes ecstatic union and the transformation of desire.

- The Five-deity Mandala of Vajravarahi is central to Nyingma and Dzogchen teachings.

Each mandala is thus not only a visual field but a lineage treasure, passed down with ritual transmission and artistic continuity.

Mandala as a Contemporary Icon

In recent decades, mandalas have traveled far beyond Tibetan monasteries. As symbols of wholeness, healing, and sacred space, they have been embraced by modern psychology (Jung saw the mandala as a symbol of the Self), art therapy, and global spiritual communities.

Yet their original context should not be forgotten. For Tibetan Buddhism, the mandala is not merely a symbol—it is a living presence, a training ground for consciousness, and a doorway to the realization of one’s Buddha-nature.

Conclusion: Sacred Design as Inner Architecture

Mandalas embody a core principle of Tibetan visual philosophy: that form is not an obstacle to spirit, but its vehicle. Through sacred geometry, they encode a vision of reality that is simultaneously vast, ordered, and transcendent. They are works of art, yes—but more than that, they are technologies of enlightenment, designed to reshape the viewer’s perception, identity, and relationship to the universe.

In every grain of sand and every stroke of pigment, the mandala whispers a radical proposition: that the chaos of life has a pattern, and at its center lies not fear or fragmentation, but clarity, compassion, and luminous awareness.

Sculpture and the Role of Craft Guilds

While Tibetan Buddhist art is often associated with painted thangkas and intricate mandalas, it is in sculpture that we encounter some of its most tactile, enduring, and spiritually resonant expressions. Sculptures—whether cast in bronze, carved from wood, or modeled in clay—serve not only as objects of devotion but as embodiments of enlightened presence. From diminutive tsa-tsa votives to monumental statues dominating temple halls, Tibetan sculpture reflects a fusion of craftsmanship, theology, and cultural exchange. Behind this visual splendor stood a powerful system of craft guilds, especially those of Newar artisans, whose technical mastery and religious insight helped define Tibetan aesthetics for centuries.

Origins and Early Influences

The roots of Tibetan Buddhist sculpture lie in the art of India’s Pala Empire (8th–12th century) and Nepal’s Newar workshops, both of which supplied the earliest models and artisans for Tibetan commissions. Pala sculptures, typically made in black stone or gilt bronze, were characterized by symmetrical balance, refined ornamentation, and serene expressions. Newar artists, meanwhile, brought a flair for ornamental richness and technical precision, especially in lost-wax casting, repoussé, and inlay techniques.

These stylistic foundations were not passively copied in Tibet. They were localized and adapted—deities gained bulkier physiques, broader faces, and a more assertive physical presence to suit the Tibetan aesthetic taste, which favored dynamism and spiritual power. Regional variations began to emerge, and by the 13th century, a distinctly Tibetan sculptural idiom was taking form.

Materials and Methods: Bronze, Clay, and Gold

Tibetan sculpture is defined by its materials—each chosen with ritual intent and spiritual symbolism.

- Bronze and Copper Alloy: The most prestigious material, used for finely cast images of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and tantric deities. The lost-wax casting method (cire-perdue) allowed for extraordinary detail, from delicate fingers to bejeweled crowns.

- Gilded Bronze (Gilt Copper): Many of the most prized Tibetan sculptures are finished in fire-gilded gold leaf. The gilding was not simply decorative—it signified purity and divine radiance. Inlays of turquoise, coral, or lapis lazuli enhanced the preciousness and sacred power of the image.

- Clay and Stucco: Used for large-scale figures embedded into temple walls or entire sculptural ensembles. These materials allowed more expressive modeling, often painted and adorned with real textiles or jewelry.

- Wood and Stone: Though less common, carved wooden deities and stupas exist, especially in remote monasteries. Stone was primarily used for architectural reliefs, stupas, or occasionally for early votive stele.

Each sculpture was a product of ritualized craftsmanship. Before casting, a sculptor would often perform purification rituals and recite prayers. Upon completion, the statue was consecrated by inserting mantras, relics, and sacred scrolls into a cavity within its body—transforming it from metal into a living presence.

Iconography and Artistic Demands

Tibetan sculptors worked under strict iconographic constraints. The proportions, postures, attributes, and facial expressions of a figure were dictated by canonical texts and passed down through lineages of artists. A sculpture of Avalokiteshvara, for example, had to include specific hand gestures, an antelope skin over the left shoulder, and eleven heads or a thousand arms if portrayed in one of his more elaborate forms.

Despite these restrictions, there was room for creativity—in facial expressions, in the subtle tilt of a head, or in the rendering of a garment’s folds. Over time, the “ideal beauty” of a deity began to reflect the ethos of the sculptor’s region and training. Some statues exhibit an intense spiritual calm; others bristle with wrathful power. In all cases, however, the underlying intention was the same: to evoke the presence of a perfected being who could guide, protect, or embody enlightenment.

The Newar Legacy and the Artist Guilds

The true golden age of Tibetan sculpture would not have been possible without the Newar artisans of the Kathmandu Valley, whose guilds—passed down through family and apprentice systems—dominated Himalayan sculpture from the 12th through 17th centuries.

These artists were not merely craftsmen—they were ritually trained, often multilingual, and familiar with Buddhist scriptures and tantric iconography. They moved across the Himalayas at the invitation of Tibetan patrons, creating statues for major monastic centers such as Sakya, Shalu, and Gyantse.

Their style was unmistakable: elegant proportions, luxurious ornamentation, and a jewel-box quality that combined devotion with precision. The fusion of Tibetan iconographic rigor with Newar stylistic flourishes produced some of the finest bronze statuary in the Buddhist world.

By the 15th century, Tibetan artists began to emerge from Newar influence, developing their own schools of metalwork. Tibetan sculptures became heavier, more robust, and more emotionally direct. Wrathful deities took on truly terrifying visages, while peaceful Buddhas exuded increasing solidity and presence.

Sculpture in Ritual and Daily Life

Sculptures in Tibetan Buddhism were not passive art objects—they were central to ritual life. Large statues served as focal points in temple halls, anchoring the spiritual gravity of the space. Smaller images were used for personal devotion, carried by monks in travel shrines or placed on home altars. Others were created as merit offerings, commissioned by lay patrons to accrue karmic benefit for themselves or deceased relatives.

Many statues were created with specific ritual functions: to house protective spirits, act as vessels during initiation ceremonies, or be buried inside stupas and prayer wheels. In tantric contexts, sculpture was also used for visualization practices, where practitioners would mentally dissolve the image into light, internalize its form, and unite with the deity’s essence.

Because of these roles, every part of a sculpture—down to the materials used and the time of casting—was chosen for maximum spiritual efficacy.

Regional Styles and Innovations

Tibetan sculpture developed regional variations, each reflecting local patronage, material availability, and stylistic preferences:

- Tsang (Central Tibet): Associated with the powerful Sakya school, sculpture here tends to be bold, architectonic, and spiritually intense.

- Amdo and Kham (Eastern Tibet): Known for expressive clay sculpture and large wall reliefs, with a greater emphasis on narrative.

- Western Tibet (Guge and Ladakh): Retained closer ties to Kashmiri and Indian models, with fine bronze and stone carving traditions.

Even within a single region, variations could occur depending on the artist’s lineage. Some favored lean, elegant forms; others preferred muscular, commanding presences.

The Decline and Continuation of Guild Traditions

With the 17th-century consolidation of the Gelug school under the Fifth Dalai Lama, Tibetan sculpture became increasingly centralized and formalized. Large-scale state commissions—such as those in the Potala Palace—led to more standardized and courtly styles. The role of individual artisans became more anonymous, and the great itinerant guilds began to diminish.

Yet the craft never disappeared. In modern Tibet and across the diaspora, traditional sculptors continue to train, create, and innovate. Workshops in India, Nepal, and Bhutan still produce ritual images in the old ways—blending sacred geometry with artisanal care.

Conclusion: Living Icons in Metal and Clay

Tibetan sculpture is the materialization of a philosophical worldview in three dimensions. It embodies not just the outward form of a deity but the internal architecture of awakening. Behind every statue lies a network of ritual, labor, transmission, and vision—where the artist serves not just as a craftsman but as a spiritual conduit.

These works are not meant to be admired in the Western sense of “art for art’s sake.” They are living beings, forged in devotion and intended to serve. In their gaze, the devotee sees not just a god, but a mirror of their own potential.

Architecture of Faith: Monasteries, Stupas, and Fortresses

Tibetan architecture is a fusion of spiritual purpose, environmental adaptation, and cultural synthesis. It is not merely the backdrop to Tibetan art but its container, amplifier, and often its very source. From the austere grandeur of cliffside hermitages to the palatial complexity of monastic citadels, Tibetan religious architecture serves both symbolic and practical functions: it maps the cosmos, sanctifies the land, and reflects the power dynamics between religion and state. Each stone, beam, and courtyard is part of a larger visual theology—a built environment that guides the practitioner’s body and mind toward awakening.

Sacred Foundations: The Cosmological Blueprint

In Tibetan Buddhism, buildings are not constructed arbitrarily. Monasteries and temples are often situated according to geomantic principles drawn from Indian vastu shastra, Chinese feng shui, and indigenous Tibetan beliefs. Locations are chosen for their auspiciousness: the meeting of rivers, the embrace of protective mountains, or the intersection of ley-like energy channels (lungta). The land itself is seen as a living being—often a goddess or spirit whose balance must be maintained.

The layout of many Tibetan temples reflects the structure of a mandala, with a central shrine representing the deity’s palace, surrounded by symmetrical subsidiary chapels and enclosing walls. This design allows practitioners to physically circumambulate sacred space, moving through a visual and spatial metaphor of the spiritual path. The act of walking itself becomes meditative—body aligning with symbol, architecture with insight.

The Jokhang and the Birth of Tibetan Buddhist Architecture

The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, constructed in the 7th century under King Songtsen Gampo, is considered the spiritual heart of Tibet. Its architecture set the prototype for centuries to come: inward-facing courtyards, low-ceilinged prayer halls supported by wooden pillars, and richly painted murals along the inner sanctums. The Jokhang houses the Jowo Rinpoche, the most revered image of Shakyamuni Buddha in Tibet, and has functioned as a pilgrimage center, ceremonial stage, and repository of artistic treasures.

Blending Nepalese, Chinese, and indigenous elements, the Jokhang established Tibetan architecture’s fundamental character: fortress-like exteriors protecting highly ornamented, symbolically charged interiors.

Monastic Complexes: Cities of the Sacred

As Buddhism spread and schools like the Kadam, Sakya, Kagyu, and later the Gelug grew in influence, they established monastic centers that became towns in their own right. Monasteries such as Tashilhunpo, Sakya, Shalu, Drepung, and Sera were not merely places of worship but universities, libraries, courts, and administrative hubs. Some housed thousands of monks and extended over hillsides in layered terraces, whitewashed walls, and ochre roofs.

The internal structure of these monasteries often followed a standardized pattern:

- A central assembly hall (dukhang) for rituals and public teaching.

- Inner chapels and sanctums (lhakhangs) reserved for sacred images and advanced initiates.

- Monastic quarters arranged around courtyards.

- Debating courtyards where philosophical disputation occurred.

- Library rooms with floor-to-ceiling manuscripts wrapped in cloth.

The architectural language emphasized ritual flow: from public to private, outer to inner, gross to subtle—mirroring the practitioner’s spiritual journey.

Stupas (Chorten): Sacred Geometry in Stone

Perhaps the most potent architectural symbol in Tibetan Buddhism is the stupa, or chorten in Tibetan. Unlike temples, stupas are not meant to be entered. They are three-dimensional mandalas, reliquary mounds that contain sacred relics, scriptures, or the remains of great teachers. Their form—a square base, rounded dome, and spire—is loaded with symbolism: earth, water, fire, air, and space; body, speech, and mind; or the Buddha’s path from enlightenment to nirvana.

Stupas come in several canonical styles—often categorized into eight types representing key events in the Buddha’s life. Tibetan stupas may be freestanding monuments, miniature tabletop shrines, or towering structures visible from miles away. One of the most magnificent examples is the Kumbum at Gyantse, a 15th-century stepped stupa housing over 70 chapels filled with murals and sculptures. Walking its concentric levels is like ascending a spiritual spiral, with each chamber offering a deeper revelation.

Stupas are also placed at crossroads, mountain passes, and entrances to villages—as protective sentinels and reminders of the Buddha’s presence in the landscape.

Dzongs: Fortresses of the Theocratic State

Tibetan architecture also includes a form unique to the intersection of religion and governance: the dzong. These fortress-monasteries, common in Bhutan and southern Tibet, were built to serve both defensive and administrative purposes. Perched on cliffs or ridges, dzongs feature thick stone walls, strategic vantage points, and labyrinthine interiors.

The most famous example in Tibet is the Potala Palace, originally built in the 7th century and greatly expanded by the Fifth Dalai Lama in the 17th century. Part residence, part temple, part administrative center, the Potala epitomizes the union of religious charisma and political power. Rising in tiers of red and white over the city of Lhasa, it is both a symbol of Tibetan identity and a masterpiece of Himalayan architecture.

Interior Aesthetics: Immersive Sacred Space

Inside Tibetan religious structures, the senses are overwhelmed: the scent of incense, the flickering of butter lamps, the drone of chanting, and the shimmer of gold and pigment. Walls are covered in murals depicting deities, lineage masters, protector spirits, and cosmological charts. Ceilings are painted with mandalas; pillars are wrapped in brocade; altars overflow with offerings.

This immersive environment is not ornamental—it’s pedagogical. The architecture teaches, reminds, and evokes. It places the practitioner in a multi-sensory mandala, where every detail contributes to the cultivation of awareness and reverence.

Adaptation and Regional Styles

Tibetan religious architecture varies by region:

- Western Tibet (Guge, Ladakh): Retains stronger Indian and Kashmiri influences; temples are smaller, with intricately painted interiors.

- Amdo and Kham: Incorporate more Chinese and Mongolian features, including multi-tiered roofs and brighter color schemes.

- Bhutan and Nepal: Preserve hybrid fortress-temple forms like the dzong, with strong Newar and indigenous design elements.

In each case, architecture reflects local materials, climate, and cultural syncretism—adapting to high altitudes, seismic activity, and regional spiritual concerns.

Conclusion: Structures of Devotion and Power

Tibetan religious architecture is far more than engineering—it is an art of symbolic inhabitation. Through the deliberate arrangement of space, material, and iconography, it creates environments that guide both communal ritual and individual transformation.

These buildings are not static relics—they are living organisms, activated by prayer, music, incense, and memory. They house not just images, but entire cosmologies. And in doing so, they remind us that in Tibetan culture, the sacred is not distant or abstract—it is something you can walk through, kneel within, and climb toward.

The Sakya, Kagyu, Nyingma, and Gelug Schools: Stylistic and Iconographic Variations

Tibetan Buddhism is not a monolith—it is a dynamic tradition shaped by multiple schools, each with its own philosophies, practices, and artistic identities. The four major schools—Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug—emerged across centuries, in different regions, under different historical pressures. Though united by core Buddhist principles and a shared tantric cosmology, these schools cultivated distinctive styles of art, iconography, and visual symbolism, often reflecting their ritual emphases and theological priorities.

Understanding these variations is essential not only for reading Tibetan art but for appreciating how visual expression became a battleground—and a bridge—between sectarian identity, spiritual authority, and regional aesthetics.

Nyingma: The Ancient School and the Art of Revelation

The Nyingma (“Ancient”) school traces its roots to the first dissemination of Buddhism in Tibet during the 8th century, especially to the legendary figure of Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche). Nyingma art is suffused with themes of mythic origin, tantric revelation, and visionary experience. It emphasizes spontaneous realization and often depicts wrathful and erotic deities from the Dzogchen and Mahayoga tantras.

Visually, Nyingma art tends to favor rich, emotionally expressive imagery, particularly of Padmasambhava in his many forms. His depictions are often surrounded by his eight manifestations, consorts, and retinue of tantric protectors. One sees a strong emphasis on terma deities—gods and goddesses revealed by treasure-revealers (tertöns) in visions or dreams.

Stylistically, early Nyingma thangkas (especially in Eastern Tibet) often exhibit fluid, almost surreal compositions—floating deities, vivid color contrasts, and thick lines—meant to mirror the dreamlike quality of visionary experience. While Newar influences are present, there’s a tendency toward visual looseness and emotional dynamism.

Kagyu: The Mystic Lineage and Yogic Imagery

The Kagyu (“Oral Lineage”) school places strong emphasis on direct experience, meditative realization, and yogic practice. Founded in the 11th century, it claims descent from Indian masters like Tilopa and Naropa, and Tibetan yogis such as Marpa, Milarepa, and Gampopa.

Kagyu art is deeply informed by the practices of mahamudra (the great seal) and guru yoga, and frequently depicts lineage holders in ascetic postures—Milarepa with his cupped ear, Gampopa with monastic robes, or Marpa in princely dress. There is a strong emphasis on personal transmission, and lineage thangkas often include long chains of teacher portraits.

The Karma Kagyu sub-school helped develop the Karma Gardri painting style, characterized by naturalistic landscapes, subtle tonal modeling, and softer outlines. This style incorporates Chinese-style clouds and horizon lines, offering a contrast to the more diagrammatic Gelug or Sakya works. Wrathful deities like Mahakala, Vajrayogini, and Chakrasamvara feature prominently, often depicted with dramatic energy, black backgrounds, and flaming halos.

Kagyu sculpture reflects a blend of devotional simplicity and tantric intensity, with bronze and gilt figures emphasizing posture and mudra over ornate decoration.

Sakya: Scholarly Austerity and Esoteric Lineage

The Sakya (“Pale Earth”) school rose to prominence in the 13th century, especially under Mongol patronage. Known for its rigorous scholasticism and tantric syncretism, Sakya developed sophisticated ritual systems—particularly the Lamdre (Path and Its Fruit) teachings—which emphasized detailed visualization and deity yoga.

Sakya art often reflects this esoteric precision. Its thangkas and murals exhibit balanced compositions, rich iconographic complexity, and muted, earth-toned palettes. Gold-on-black paintings (nag thang) were especially favored, creating dense, diagrammatic renderings of deities and mandalas against dark backgrounds. This style evoked sacred mystery and scholastic depth, mirroring the textual richness of Sakya ritual manuals.

Key figures like Sakya Pandita and Butön Rinpoche are frequently depicted, often surrounded by multi-deity mandalas of tantric cycles like Hevajra or Vajrakilaya. The architecture at Sakya Monastery also reflects the order’s visual signature: thick walls, austere interiors, and towering temples designed to inspire awe and introspection.

Sculpture in the Sakya school often prioritized iconographic accuracy over expressive flourish, resulting in forms that are simultaneously formal and metaphysically dense.

Gelug: Monastic Order and Iconographic Codification

The Gelug (“Way of Virtue”) school, founded in the 15th century by Je Tsongkhapa, became Tibet’s dominant religious and political force under the Dalai Lamas. Gelugpa emphasized monastic discipline, scholastic rigor, and centralized authority, and its art reflects this drive toward standardization and clarity.

Gelug thangkas are often painted in the Menri style, with clean lines, jewel-toned palettes, and symmetrical arrangements. These works are pedagogical tools—visual aids for scholastic study, debate, and ritual—and emphasize lineage trees, protector deities, and systematized mandalas.

Key figures include Tsongkhapa, depicted with yellow hat and sword of wisdom; the successive Dalai Lamas; and tantric deities like Yamantaka, Guhyasamaja, and Kalachakra. Gelug art often includes text annotations, meticulous deity identification, and architectural borders that reflect its scholastic orientation.

Sculpture in the Gelug tradition emphasizes refinement and order, often with idealized features, highly polished gilding, and carefully composed postures. Large-scale figures—like the monumental Maitreya statues in Lhasa or Tashilhunpo—reflect both spiritual grandeur and state patronage.

Cross-School Exchanges and Shared Iconography

Despite their differences, the four schools share a vast body of common iconography. Deities like Tara, Avalokiteshvara, and Padmasambhava appear across traditions, albeit with different emphases. Likewise, artistic techniques—gilding, mineral pigments, composition—were often shared between workshops, especially in urban centers or border regions.

Artists themselves frequently worked across sectarian lines. A Newar sculptor might create statues for both Kagyu and Gelug patrons; a painter trained in the Menri style might adapt his work for a Nyingma monastery. This fluidity of labor and influence complicates any rigid sectarian reading of Tibetan art, reminding us that visual culture often transcended doctrinal boundaries.

Conclusion: Diversity Within Devotion

The art of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism reveals how visual tradition reflects—and shapes—spiritual identity. From the visionary dynamism of Nyingma to the yogic immediacy of Kagyu, from the tantric exactitude of Sakya to the scholastic order of Gelug, each lineage crafted its own aesthetic theology.

Yet all shared a conviction in the power of image: to transform, to teach, to invoke, and to embody. In the interplay between difference and commonality, Tibetan art achieved its remarkable balance—dynamic, pluralistic, yet unified by devotion and insight.

Art Under the Theocracy: The Dalai Lamas and State Patronage

From the mid-17th century onward, Tibetan art entered a new era—one defined by theocratic rule, centralized authority, and an unprecedented scale of religious and political patronage. With the rise of the Gelug school and the establishment of the Ganden Phodrang government under the Fifth Dalai Lama, Tibet became not just a land of monasteries but a sacralized state governed by an incarnate lama-king. This fusion of religious charisma and temporal power had profound consequences for Tibetan visual culture.

The state now actively commissioned art on a monumental scale—murals, thangkas, sculptures, reliquaries, and architectural projects—not merely as devotional works, but as tools of legitimacy, diplomacy, and statecraft. Art was no longer only the domain of monks and yogis—it had become a language of rule.

The Fifth Dalai Lama and the Vision of a Unified Tibet

The figure who inaugurated this transformation was Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617–1682), the Fifth Dalai Lama. With the military backing of the Mongol ruler Gushri Khan, he consolidated power in central Tibet and assumed both spiritual and temporal leadership. In 1642, he founded the Ganden Phodrang government, headquartered at the Potala Palace in Lhasa.

The Fifth Dalai Lama was a visionary—deeply learned in both Gelug and Nyingma teachings, fluent in diplomacy, and keenly aware of the symbolic power of art. Under his rule, art became an expression of unity: between sects, between Tibet and its neighbors, and between the worldly and the spiritual realms.

The reconstruction and massive expansion of the Potala Palace, begun in 1645, stands as the supreme visual manifestation of this vision. A towering architectural mandala, it was not just the Dalai Lama’s residence but the center of Tibetan religious-political cosmology, housing relics, ceremonial halls, libraries, and gilded tomb stupas.

Monumental Art and Political Messaging

The Potala set a new standard for artistic production: scale, coordination, and symbolism. Its murals cover hundreds of square meters, depicting everything from cosmic mandalas to historical events—including diplomatic audiences, enthronements, and religious transmissions. These images were carefully curated to tell a story: that of a divinely guided, legitimate Tibetan state with spiritual supremacy over its territory.

This monumental style was emulated in other Gelug centers, such as Tashilhunpo Monastery, home of the Panchen Lamas, and the great monasteries of Sera, Drepung, and Ganden. In these institutions, thangkas and sculptures were not only used for worship, but for ritual display during festivals, processions, and imperial ceremonies. Gigantic thangkas (some dozens of meters tall) were unrolled on hillside walls during celebrations like Monlam, reinforcing communal identity and divine sanction.

The art of this period emphasized polish, consistency, and precision. Gelug thangkas followed strict guidelines for iconography and composition, ensuring theological accuracy and visual uniformity. This created a kind of visual orthodoxy—an “official style” that mirrored the centralizing tendencies of the state.

The Role of State Workshops and Sponsored Artists

To support such vast production, the Ganden Phodrang government established state-sponsored workshops—guilds of painters, metalworkers, woodcarvers, and textile artists. These included both Tibetan and Newar artisans, many of whom worked exclusively for elite clients.

Artistic training was rigorous, emphasizing replication of models, knowledge of iconometric treatises, and mastery of technique. Individual creativity was often subordinated to canonical accuracy, but this didn’t mean the art was lifeless. Many state-commissioned works from this era—especially gilt bronze sculptures and embroidered thangkas—are among the finest technical achievements of Tibetan art history.

Patronage extended beyond temples. The Dalai Lama’s court commissioned art for gifts to foreign rulers—including the Chinese emperor, Mongol khans, and Bhutanese kings. These diplomatic offerings, often in the form of reliquaries, thangkas, or manuscripts, acted as visual envoys of spiritual legitimacy.

Secular and Historical Narratives in Art

Another innovation of the theocratic era was the rise of historical painting—murals and thangkas that depicted not just Buddhas and deities, but real events, genealogies, and biographies of saints and rulers. This is especially evident in the murals of the White Palace at the Potala, where entire walls are devoted to the life of the Fifth Dalai Lama, his visions, and his interactions with Mongol and Chinese envoys.

Such narrative art blurred the line between hagiography and history, elevating the political past into the realm of the sacred. Even scenes of military campaigns or palace meetings were rendered in a visual idiom traditionally reserved for tantric gods, lending them an aura of divine predestination.

This trend continued under later Dalai Lamas, who used art to celebrate diplomatic victories, spiritual accomplishments, and architectural projects. The “Great Fifth” became the prototype of the lama-ruler whose legacy was immortalized not only in texts but in brush and stone.

Theocracy and Control of Iconography

With centralized power came increased control over iconographic canons. The Gelug school’s dominance ensured that certain deities—especially Yamantaka, Kalachakra, and Guhyasamaja—were emphasized, while others, more common in Nyingma or Kagyu circles, were sidelined.

New images were sometimes created to reinforce Gelug supremacy. For example, Tsongkhapa, the school’s founder, was often portrayed surrounded by Buddhas and bodhisattvas, with iconographic parity to Padmasambhava in Nyingma art. The visual culture of the period subtly encoded sectarian hierarchies even as it aimed for spiritual inclusiveness.

At the same time, the Gelug establishment also commissioned art in multiple regional styles, including Karma Gardri and Bhutanese modes, as a way of incorporating and pacifying other traditions.

Legacy and Continuity

The tradition of state-sponsored art continued well into the 19th and early 20th centuries. The 13th Dalai Lama (1876–1933), for instance, initiated restoration projects, commissioned murals depicting political reforms, and promoted photography as a documentary medium alongside traditional painting.

By then, the political role of art was fully institutionalized. Every monastery, court, and ritual contained layers of visual messaging, signaling not only spiritual ideals but temporal allegiance, lineage, and legitimacy.

Though the Chinese invasion and the subsequent diaspora of Tibetan communities in the mid-20th century disrupted this system, many of its artistic practices survived—carried by refugee lamas, preserved in monasteries-in-exile, and revived through contemporary commissions.

Conclusion: The Sacred Image as Statecraft

Under the rule of the Dalai Lamas, Tibetan art reached new heights of institutional scale, iconographic consistency, and political purpose. No longer just expressions of personal devotion or monastic meditation, art became a tool of rule—a visual system through which theocratic authority was projected, preserved, and sanctified.

Yet even amid this centralization, Tibetan art retained its core function: to reveal the invisible, evoke the sacred, and transform the viewer. The walls of the Potala, the bronzes of Tashilhunpo, and the giant thangkas of the Gelug festivals remind us that in Tibetan culture, the state was never just a government. It was a mandala in motion—its axis not power, but awakening.

Encounters with Modernity: 20th-Century Transformations and the Tibetan Diaspora

The 20th century brought immense upheaval to Tibet—political, social, and spiritual—and with it came a profound transformation in the world of Tibetan art. Once the product of monastic workshops and court patronage, Tibetan visual culture was now confronted with colonialism, nationalism, exile, and globalization. Amid the trauma of occupation and displacement, traditional art forms both struggled and adapted, emerging in new contexts with new meanings.

Tibetan artists, teachers, and craftsmen, once working within a unified religious state, now found themselves scattered across the Himalayas and the world. Yet the crisis of modernity also sparked a creative reimagining of what Tibetan art could be: a vehicle of memory, a tool of cultural survival, and a bridge between ancient tradition and global modernity.

The 1950 Invasion and Cultural Suppression

In 1950, the People’s Liberation Army of China entered Tibet, and by 1959, following the failed uprising and the 14th Dalai Lama’s flight to India, Tibet had come under full Chinese control. The impact on the arts was devastating. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), monasteries were destroyed, statues melted down, murals defaced, and religious practice outlawed.

This period witnessed the near-total destruction of institutional art production in central Tibet. Master artisans were imprisoned, monastic guilds were disbanded, and sacred images were desecrated or hidden away by villagers who risked their lives to protect them. What had once been a thriving ecosystem of religious art became a landscape of ruins.

Yet even in this darkness, fragments of the tradition survived. Some artists went underground, painting secretly. Others smuggled sacred texts and thangkas out of Tibet. The oral transmission of techniques—never fully reliant on written manuals—persisted in whispers and memory.

The Tibetan Diaspora: Art in Exile

With the exodus of Tibetans into India, Nepal, and Bhutan, a new chapter in Tibetan art began. Dharamsala, Bodh Gaya, and Kathmandu became cultural hubs where displaced monks, scholars, and artists attempted to rebuild Tibetan religious life in unfamiliar terrain.

One of the earliest and most significant projects was the creation of institutes for traditional arts, such as the Norbulingka Institute (founded in 1995) and the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. These schools sought to revive painting, sculpture, wood carving, and textile work, not just as religious practices but as cultural heritage. Artists trained here produced thangkas, statues, and architectural ornamentation in continuity with pre-1959 traditions, now preserved through formal curriculum.

Other exiled artists began to reinterpret traditional forms in new materials and contexts. Some used Western media—oil paint, photography, video—while retaining Buddhist themes. Others created hybrid works that blended sacred motifs with political commentary, autobiographical reflection, or surrealist influence.

In this diaspora, Tibetan art became both a repository of memory and a site of innovation.

The Politicization of Image

In exile, Tibetan art often took on a political dimension. Thangkas and mandalas were no longer only ritual objects but cultural ambassadors—tools of advocacy, education, and resistance. Exhibitions of Tibetan art in Europe and North America were used to raise awareness about the situation in Tibet, human rights abuses, and the loss of a unique civilization.

Images of the 14th Dalai Lama, previously reserved for altar shrines, became iconic symbols of identity and longing. Portraits of destroyed monasteries, weeping Bodhisattvas, or broken mandalas became metaphors for a fractured homeland.

Art was also a means of diplomacy and soft power. The Tibetan government-in-exile supported the production of murals, performances, and exhibitions to assert cultural sovereignty on the world stage. In doing so, they reframed Tibetan art not just as a religious tradition, but as a world heritage at risk of extinction.

Tourism, Commodification, and the Art Market

In Nepal and parts of India, the growing interest in Tibetan spirituality brought both support and challenges. On the one hand, international demand for thangkas and statues created a new market that sustained refugee communities. On the other, it introduced the risk of commodification, as artworks were increasingly made for tourist aesthetics rather than spiritual function.

Workshops began producing mass-market thangkas—bright, decorative, but sometimes iconographically inaccurate. The sacred was rendered as the exotic, repackaged for sale. This raised ethical questions among traditionalists: Could a thangka made for a gift shop still function as a sacred object? What happens when ritual becomes commodity?

Yet some artists used this platform to reach global audiences, educating collectors and curators about the deeper meanings behind the images, and advocating for ethical patronage and cultural respect.

Survivals Inside Tibet: Art Under Surveillance

Inside the PRC-controlled Tibet Autonomous Region, traditional art began to re-emerge in the 1980s, when some religious restrictions were lifted. Monasteries reopened, and the government began to support cultural preservation—though under strict regulation.

Some monasteries, such as Tashilhunpo, Sera, and Drepung, resumed mural restoration and thangka painting. However, these efforts were tightly monitored, with content vetted for political acceptability. Images of the Dalai Lama, for instance, were banned, and nationalist themes were sometimes inserted into traditional formats.

At the same time, a small number of Tibetan artists in Tibet began to create non-traditional art, often navigating the line between spiritual symbolism and state censorship. Their works speak in coded language, blending religious motifs with abstract forms, personal trauma, or subtle critique.

These artists often operate in ambiguity—not overtly political, but still deeply subversive in their commitment to preserving Tibetan visual identity.

Contemporary Hybrids: Global Voices and New Mediums

In recent decades, a generation of contemporary Tibetan artists has emerged, both in exile and within the PRC, creating work that draws on traditional forms while exploring identity, memory, modernity, and exile.

Figures such as:

- Tenzing Rigdol, whose installation Our Land, Our People brought soil from Tibet to India, creating a temporary homeland for exiled Tibetans.

- Gonkar Gyatso, who combines thangka iconography with pop culture, street art, and political satire.

- Dedron and Penpa, whose work engages with gender, identity, and the feminine divine in Tibetan culture.

These artists do not reject tradition—they remix it, using Tibetan symbols to speak to global audiences and personal histories. Their work exists in dialogue with Western contemporary art while remaining rooted in the symbols of Tibetan cosmology.