Tucked into the limestone hills of the Lot department in southern France, the Pech Merle cave offers a stunning glimpse into the artistic vision of humanity’s distant past. Located near the village of Cabrerets, this cave is part of a vast prehistoric network that includes other famous sites such as Lascaux and Chauvet. What makes Pech Merle so unique, however, is the remarkable panel known as the “Spotted Horses,” painted around 25,000 BC during the Gravettian period of the Upper Paleolithic. This particular artwork has intrigued archaeologists, artists, and historians for generations due to its unusual depiction of horses with spotted coats and the mystery surrounding their purpose.

Discovered in the early 20th century, the Pech Merle cave is more than a cultural artifact—it’s a time capsule. Over two miles long, the cave contains multiple chambers adorned with wall paintings, engravings, and hand stencils that appear to tell a visual story from an era long before written language. Among the most compelling images is the Spotted Horses panel, which features two large horses marked with black spots, accompanied by human handprints in a similar pattern. These images are not merely decorations; they represent the complex minds of early humans and possibly reflect aspects of their environment, beliefs, or even identity.

The age of the Pech Merle paintings was determined through radiocarbon dating of associated materials, revealing that the artwork was created around 25,000 years ago. This places it within the Gravettian cultural period, known for its advances in stone tools, body ornamentation, and—most notably—figurative art. The depth of skill and symbolism evident in the Spotted Horses has prompted scholars to debate whether the markings were imagined, stylized, or an accurate reflection of animals that existed in that time. The answer to this question, long elusive, has only recently become clearer thanks to modern scientific tools.

What draws modern viewers to the Spotted Horses is not just the age of the paintings or their location deep within a cave—it’s the artistry and mystery. Are these horses totems of spiritual significance? Were they part of a storytelling tradition or a kind of prehistoric visual diary? Or were they painted simply because they resembled real creatures roaming the plains of Ice Age France? These questions frame our exploration of the Pech Merle cave, where art and archaeology meet in one of the oldest surviving art galleries on Earth.

Discovery and Excavation of the Pech Merle Cave

The story of Pech Merle’s discovery reads more like an adventure novel than an academic dig. In 1922, two French teenagers—Marthe and André David—were exploring the hills near their home in Cabrerets when they stumbled upon the cave. Their curiosity led them deep into the underground passages, where they first encountered the mysterious paintings on the walls. Recognizing the significance of what they found, they brought word to the local parish priest, who happened to be an amateur archaeologist.

That priest was Father Amédée Lemozi, born in 1882 and ordained in 1907, who played a pivotal role in the excavation and documentation of the site. Lemozi devoted much of his life to studying the Pech Merle cave, producing detailed drawings, records, and publications that became foundational to the understanding of Paleolithic art in France. His work emphasized both the artistic value and the cultural implications of the cave’s contents. Father Lemozi’s efforts, undertaken throughout the 1920s and 1930s, helped preserve the site and elevate its importance in the academic community.

Throughout the mid-20th century, archaeologists continued to excavate and analyze the cave using evolving scientific techniques. These included sediment analysis, charcoal sampling, and microstratigraphy, which allowed researchers to assign more accurate dates to the artwork and associated cultural layers. Although the cave was open to the public in later decades, scientists quickly realized that human presence was contributing to the deterioration of the artwork. As a result, stricter controls were introduced to limit access and preserve the cave’s fragile ecosystem.

Today, only a few visitors are allowed to enter the Pech Merle cave each day, with tours carefully managed to balance public interest with preservation. The Pech Merle Museum nearby provides a comprehensive educational experience for those who cannot access the original site, featuring replicas and interactive exhibits. Thanks to the courage of two curious teenagers and the lifelong dedication of Father Lemozi, the world can appreciate this unique cultural treasure. Their names are forever tied to one of the most important prehistoric discoveries in Europe.

Description and Style of the Spotted Horses Panel

The Spotted Horses panel is located deep within the Combel Gallery of the Pech Merle cave system, requiring a journey into one of the cave’s darker, more intimate chambers. This remote location suggests that the painting may have had special significance to the people who created it. Measuring over five feet in length, the panel features two horses facing left, their bodies decorated with bold black spots and framed by hand stencils. The horses are painted in shades of black and brown, using natural pigments derived from charcoal and iron oxide, giving them a bold contrast against the light limestone walls.

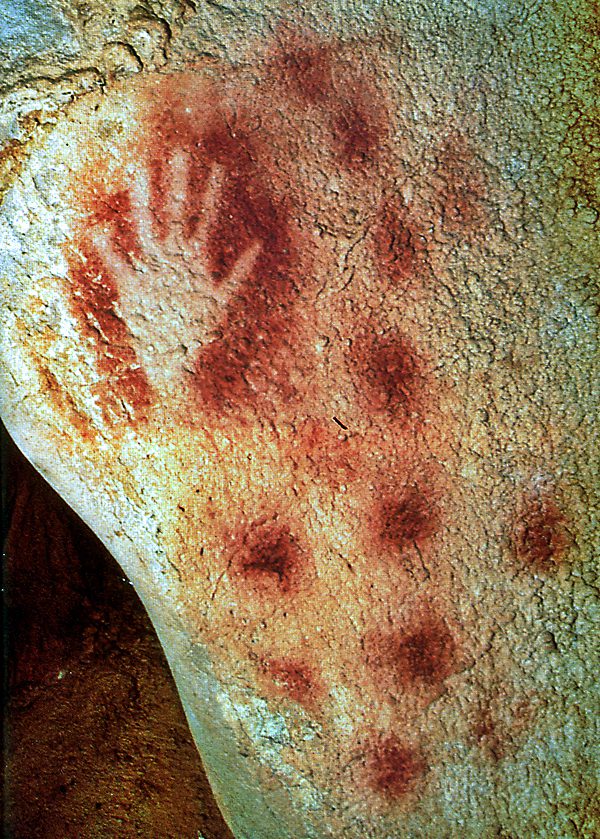

One of the most remarkable aspects of this artwork is its use of both painting and stenciling techniques. The spotted effect was created by spraying pigment around a hand-held stencil or directly from the mouth, allowing the artists to “dot” the horses with remarkable precision. This technique was also used for the surrounding negative handprints—ghostly outlines of human hands that seem to echo from the ancient past. These stencils are believed to have been created by placing the hand against the wall and blowing a mix of pigment and air, leaving behind an eerie yet deliberate imprint.

The horses themselves are depicted with keen anatomical awareness, showing careful attention to proportion, posture, and movement. Their heads are well-defined, and the curvature of their backs and legs suggests motion and vitality. Despite the limited tools and conditions available in the cave’s depths, the artists achieved a high level of visual sophistication. The contrast between the stylized spots and realistic form invites interpretation: were these markings decorative, spiritual, or documentary in nature?

Lighting played an essential role in the visual experience of the painting. Because the cave was naturally pitch-black, the original artists likely used stone lamps fueled by animal fat to illuminate the walls as they worked. This flickering light would have created dramatic shadows, making the horses appear to move or shift as one walked past them. Today, visitors often view the panel with similar awe, though under tightly controlled conditions. The interplay of art, environment, and human ingenuity in this single panel speaks volumes about the creative spirit of early humans.

Symbolism and Interpretations Over Time

When the Spotted Horses were first studied in the 1920s and 1930s, many scholars believed the markings were symbolic or totemic in nature. Some theorized that they represented spiritual or shamanistic beliefs, perhaps tied to fertility, weather control, or communication with the spirit world. Others argued that the negative handprints indicated some form of individual or communal identity, a kind of prehistoric “signature.” These interpretations, while imaginative, were difficult to prove and relied heavily on modern anthropological theories imposed on ancient minds.

Throughout the 20th century, interpretations of the panel evolved. The “hunting magic” theory gained traction, suggesting that cave paintings were intended to influence successful hunts by invoking animal spirits. According to this view, early humans painted animals they wanted to catch, believing the act would grant them power or luck. The spotted horses, then, might have been linked to a specific herd or territory. However, this interpretation began to lose favor as more evidence emerged that some cave animals—like lions or mammoths—were rarely hunted, if at all.

Comparative studies with other Upper Paleolithic sites such as Lascaux and Chauvet have shown both similarities and differences in animal depiction. Horses appear frequently across all these sites, but rarely with the same level of abstraction found in Pech Merle’s spotted coats. In Chauvet, dated to around 30,000 BC, horses are drawn with fluid lines and dynamic motion but lack the deliberate dotted patterns. This contrast suggests that the spotted motif may have held special significance for the people of Pech Merle or reflected a regional tradition.

While interpretations have expanded over time, many scholars now approach such paintings with caution, avoiding overly speculative narratives. The lack of written records means we may never know the exact meaning behind the images. What is clear, however, is that the Spotted Horses reflect a high degree of intentionality and creativity. Whether symbolic, decorative, or documentary, these images continue to challenge modern assumptions about prehistoric life and thought.

Scientific Analysis and DNA Research on Prehistoric Horses

In 2011, a groundbreaking study changed the way we view the Pech Merle Spotted Horses. An international team of scientists led by Arne Ludwig from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research conducted a DNA analysis on the remains of prehistoric horses from various European sites. Their research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, revealed that some Upper Paleolithic horses carried the “leopard complex” gene, responsible for a spotted coat pattern. This was the first genetic evidence that horses with such markings existed during the time the paintings were created.

The implications of this discovery were significant. Prior to this study, many experts believed the Pech Merle artists had imagined or stylized the horses with decorative patterns. With the confirmation that real spotted horses roamed Ice Age Europe, the Pech Merle artwork could now be considered a realistic portrayal rather than a symbolic abstraction. This reinforced the idea that Upper Paleolithic artists were keen observers of the natural world, and that their paintings could serve as accurate records of prehistoric biodiversity.

In addition to genetic testing, researchers used high-resolution imaging and microscopic analysis to further study the techniques used in the cave. These modern tools have revealed layering methods and corrections made by the artists, indicating a thoughtful and deliberate process. The artists were not simply drawing on impulse—they were crafting lasting visual representations, possibly with communal input or ritual guidance. This level of care aligns with the idea that the cave art had deep cultural or social meaning.

The 2011 DNA study has had a ripple effect in the fields of archaeology, genetics, and art history. It has prompted researchers to reexamine other depictions of animals in prehistoric art, looking for correlations between visual representation and genetic reality. As science continues to intersect with archaeology, we gain a fuller picture of life in the distant past—not just how early humans thought or believed, but what they saw with their own eyes. The spotted coats at Pech Merle, once a mystery, now stand as a testament to the accuracy and sophistication of ancient artists.

Cultural Context of Upper Paleolithic Art in France

The Pech Merle Spotted Horses do not exist in isolation. They are part of a broader cultural and artistic tradition that flourished in Europe during the Upper Paleolithic, particularly between 30,000 and 10,000 BC. This period saw the emergence of the Gravettian culture, known for its advanced stone tools, carved figurines like the “Venus” figures, and elaborate cave art. In France, this era produced some of the most iconic prehistoric sites, including Chauvet, Lascaux, Cosquer, and of course, Pech Merle. Each of these sites contributes pieces to a grand puzzle of human expression and ingenuity in ancient times.

Gravettian people were hunter-gatherers who relied on reindeer, mammoth, bison, and wild horses for survival. They moved seasonally and lived in small, tight-knit communities that likely worked together on large tasks, including the creation of cave art. These early humans used bone tools, wore necklaces made of teeth and shells, and buried their dead with care, all signs of a developing spiritual and social life. Their ability to create art deep within dark, echoing caves speaks to a strong communal effort—someone had to make the pigments, prepare the lamps, and navigate the treacherous terrain.

Cave art during this time often depicted animals—some hunted, some not—alongside human forms, abstract symbols, and stenciled hands. This has led scholars to suggest that the purpose of the art varied widely. In some cases, it may have recorded events, while in others it served ritual or mythological roles. The fact that so many different styles, subjects, and techniques appear across caves within a few hundred miles of each other suggests both shared cultural ideas and localized customs. Pech Merle’s spotted horses, for example, are unlike anything found in Lascaux or Cosquer, which may hint at a unique cultural identity for the artists who worked there.

The spiritual and cultural depth of these early societies is often underestimated. Without permanent settlements, writing systems, or agriculture, it’s tempting to think of them as primitive. But the complexity of their art challenges that assumption. These people clearly had rich symbolic lives, valued aesthetic expression, and may have possessed a worldview far more advanced than we typically credit. The Pech Merle horses stand as a visual reminder that civilization begins not with the plow, but with the imagination.

Preservation, Legacy, and Modern Engagement

As interest in prehistoric art grew throughout the 20th century, so did the challenges of preserving it. By the 1950s, the French government began restricting public access to many caves to protect their fragile environments from human damage. Carbon dioxide from breathing, artificial lighting, and even humidity from crowds had already begun to degrade paintings in Lascaux and other sites. Fortunately, Pech Merle was recognized early as a site worth protecting. Strict visitor limits and careful environmental controls have helped to maintain the integrity of its priceless artwork.

In order to make the Pech Merle experience more accessible without endangering the site, a museum and interpretive center were established near the cave. Here, visitors can view detailed replicas of the Spotted Horses panel, learn about the techniques used to create it, and explore the broader context of Paleolithic life. Digital projections, 3D models, and virtual tours help bridge the gap between past and present, ensuring that even those who cannot enter the original cave can still connect with its message. These tools are particularly valuable for educators and families, making prehistoric art tangible and relevant for future generations.

The Spotted Horses have also found a surprising second life in contemporary culture. Their mysterious aesthetic has inspired everything from modern paintings to textile designs and film imagery. Scholars, artists, and even theologians continue to ponder their meaning, drawing connections to everything from animal worship to abstract representation. Despite—or perhaps because of—their ambiguity, these images hold a timeless fascination. They remind us of the enduring power of visual storytelling and the need to preserve our shared cultural heritage.

Ongoing research into Pech Merle is supported by universities, museums, and private donors. New techniques in dating, pigment analysis, and even AI-assisted image reconstruction are being employed to learn more about the cave’s art without disturbing it. These efforts are not only scientific but moral in nature. By preserving and understanding this ancient site, we affirm a truth that transcends time: beauty, mystery, and meaning have always been part of the human story.

Key Takeaways

- The Pech Merle Spotted Horses were painted around 25,000 BC during the Gravettian period in southern France.

- Two teenagers, Marthe and André David, discovered the cave in 1922; Father Amédée Lemozi led its first excavations.

- The spotted horses likely represent real animals, as genetic studies in 2011 revealed Ice Age horses had similar coat patterns.

- The artwork reflects the cultural depth, technical skill, and symbolic imagination of Upper Paleolithic humans.

- Preservation efforts today balance public access with scientific research to protect this invaluable piece of human history.

FAQs

- Where is the Pech Merle cave located?

It is located near Cabrerets in the Lot department of southern France. - How old are the Spotted Horses paintings?

They are estimated to be about 25,000 years old, from the Gravettian period. - Who discovered the Pech Merle cave?

Siblings Marthe and André David discovered the cave in 1922. - Are the spotted horses real or symbolic?

Genetic evidence suggests the horses were based on real animals with spotted coats. - Can the public visit the Pech Merle cave?

Yes, but access is limited and tightly controlled to preserve the artwork.