To speak of Norwegian art is to confront an essential paradox: a tradition of visual culture that, though often overlooked in continental narratives, emerges with remarkable persistence from a land historically cast as peripheral, austere, and marginal. The geography of Norway—mountainous, fjord-carved, and sparsely inhabited—has always shaped its cultural rhythms. Yet what has often been dismissed as cultural remoteness has, over centuries, fostered a uniquely distilled aesthetic language, one informed by elemental nature, historical solitude, and moments of explosive contact with broader artistic movements.

For most of its modern history, Norway has not been an independent nation. From the late Middle Ages until 1814, it was a subordinate kingdom under the Danish crown; from 1814 to 1905, it entered into a personal union with Sweden. Its sovereignty, in other words, was long interrupted, and with it, its autonomous cultural development. This geopolitical status relegated Norwegian art to a curious status: frequently provincialized, often overshadowed by Danish or Swedish paradigms, and at times almost invisible in the dominant histories of Western European art. Yet this very marginality, paradoxically, gave Norwegian art the conditions for a deeper introspection, an encounter with the land and its myths that would one day produce singular voices like Edvard Munch and Johan Christian Dahl.

The artistic history of Norway cannot be understood through the lens of a continuous, institutionalized lineage like that of Italy or France. There was no Renaissance court culture, no Baroque architectural dynasty, no Enlightenment academies shaping national styles from within. Instead, there were silences—long stretches in which native visual expression was either ecclesiastical, folk, or subordinated to foreign influence. But within those silences lay latent energies. Norwegian art history is less a seamless evolution than a series of emergences—occasional yet forceful episodes in which a distinctly Norwegian aesthetic language surfaced against the odds.

The Viking Age, long romanticized in national lore, did in fact produce a rich artistic vocabulary—one embedded in metalwork, woodcarving, ship ornamentation, and funerary architecture. Yet this art was not conceived for galleries or courts; it was integral to life, myth, and ceremony. Later, the Christianization of Norway in the 11th century reoriented artistic production toward the sacred, leading to the idiosyncratic medieval forms of stave churches and painted altar panels that still survive in remote parishes. These traditions were often anonymous, deeply local, and resistant to the stylistic standardization that marked continental Europe.

After the Reformation and the formal union with Denmark in 1536, Norwegian culture was increasingly administered from Copenhagen. Local artists, if they wished to gain recognition or training, often had to emigrate or work in the service of Danish patrons. The result was both a brain drain and a cultural flattening, as native motifs and techniques were submerged beneath the imperatives of Danish Lutheran orthodoxy and academic decorum. It was not until the 19th century—specifically after the rupture of the Napoleonic Wars and Norway’s subsequent independence from Denmark—that the idea of a distinctly Norwegian visual tradition began to emerge.

This emergence coincided with the broader Romantic movement in Europe. Nationalism, landscape painting, and folk traditions provided a fertile ground for Norway’s self-discovery through art. But even then, the influence of Germany remained strong, particularly through the Dresden-based painter Johan Christian Dahl, who effectively became the father of Norwegian national painting while spending most of his life abroad. This oscillation—between home and abroad, center and periphery—has remained a defining feature of Norwegian art. Artists such as Christian Krohg, Frits Thaulow, and eventually Edvard Munch would travel widely, absorbing European currents while maintaining a stubborn, sometimes tragic relationship with their homeland.

In the 20th century, with the firm establishment of a Norwegian state, the conditions for a more institutional and autonomous artistic culture began to solidify. State patronage, public museums, art academies, and biennials created infrastructure—but not always innovation. As with many small nations, the challenge has been to avoid merely echoing international trends while also resisting the trap of folkloric nationalism. The best Norwegian artists—those who have endured—have found a third way: turning the country’s isolation into a strength, and its landscapes into meditative or psychological spaces rather than picturesque backdrops.

Today, Norwegian art occupies a curious place on the world stage. It benefits from oil wealth, cultural subsidies, and strong institutions. Its artists participate in international circuits, yet continue to reflect, in subtle ways, the austere lyricism and elemental sensibility that have long characterized Norwegian cultural expression. If one listens carefully, the entire history of Norwegian art might be read as a dialogue with silence—both the silence of marginalization and the deeper, more spiritual silence of its vast natural world.

As we proceed through this history, from prehistoric rock carvings to the complexities of contemporary practice, the goal is not to impose a false continuity where none exists. Rather, we seek to trace the arcs, ruptures, and resurgences that have given Norwegian art its singular voice: cool, luminous, reticent, but deeply resonant. This is the art of a land at the edge of Europe, looking both inward and outward, shaped as much by absence as by expression.

The Echoes of Ice and Stone: Prehistoric and Viking Art

Norwegian art does not begin with painting or sculpture in the conventional sense, but with stone. In the rugged, glacially scarred terrain of Scandinavia, the earliest surviving aesthetic expressions are etched into rock faces—carvings that date from the Mesolithic period (ca. 8000–4000 BC) through to the Bronze Age. These petroglyphs, found at sites such as Alta in Finnmark and Ekeberg in Oslo, form one of the most direct and poignant links between the prehistoric mind and the material world. They are not representational in a narrative sense; they are inscriptions of presence, ritual, and cosmology. In this, they anticipate a Norwegian aesthetic tendency that will recur across centuries: the desire not merely to depict but to integrate with the land.

The Alta rock carvings—now a UNESCO World Heritage site—are especially rich, comprising over 6,000 images carved into glacial rock over a span of millennia. They depict elk, reindeer, fish, boats, hunters, and abstract symbols whose meanings remain elusive. Unlike the heroic sculpture of classical antiquity or the myth-laden friezes of Egypt and Mesopotamia, these images emerge as gestures of survival and reverence. They suggest a culture not yet committed to art for its own sake, but one in which the act of inscribing was itself an invocation—part magic, part mapping, part testament to continuity in an unforgiving world. Art here is not separate from life; it is the echo of a necessary communion with nature and the unknown.

As we move forward into the Iron Age and the Viking period (c. 800–1050 AD), Norwegian art acquires a formal sophistication that still resists the monumental. Viking art is intensely decorative, structurally integrated into tools, weapons, ships, and domestic architecture. It is not organized into distinct genres or confined to privileged spaces. Rather, it pervades the material culture of life and death. The Oseberg ship burial, discovered in 1904 and dated to around 834 AD, remains perhaps the single greatest surviving example of this art. Found in a burial mound near Tønsberg, the ship contained the remains of two women, presumed of high status, alongside an array of goods, animals, and intricately decorated artifacts. Every surface of the ship’s prow is adorned with interlaced animal forms—serpents, dragons, and fantastical beasts that move in a rhythm at once ornamental and hieratic.

The so-called “Urnes style,” the last of the major Viking art styles (ca. 1050–1130), exemplifies the syncretism of these forms. Named after the wooden stave church at Urnes in western Norway, it represents a transitional moment between pagan and Christian aesthetics. Its motifs are slimmer, more elegant, and more abstract than earlier styles, suggesting a move away from animistic symbolism toward a symbolic order more aligned with continental Christian iconography. Yet even in these late works, the old cosmological grammar remains visible: interlace patterns, stylized animals, and serpentine forms that speak of an enchanted universe, dense with invisible forces.

This was a culture with no tradition of portraiture, no doctrine of mimesis, and no organized patronage system in the Greco-Roman sense. Its art emerged communally, often anonymously, and was embedded in ritual, craft, and belief. It was an art of surfaces—yet never superficial. What appears decorative to the modern eye was, in fact, charged with metaphysical significance. The ships themselves were not only technological feats, but also spiritual vessels—conduits for passage between worlds, both literal and symbolic. Their carvings may have served as apotropaic symbols, warding off evil and securing safe transit, whether through physical waters or the journey to the afterlife.

One of the most striking features of Viking art, especially in its Norwegian context, is its resistance to scale for scale’s sake. Where the Romans erected arches and columns to assert empire, and where Gothic cathedrals soared skyward to embody divine aspiration, Viking art stayed close to the hand and the eye. Its forms were intimate, rhythmic, and often tactile. Whether on brooches, sledges, or doorframes, its lines curve with a fluidity that mirrors the topography of Norway itself. This was not a culture bent on conquest through image, but one that modulated power through gesture, repetition, and encoded symbols. It is, in many respects, an art of silence and motion, not proclamation.

Moreover, there was in Viking art an acceptance—if not an embrace—of transience. Wood, the dominant medium in this northern culture, is ephemeral. Its survival across the centuries is rare and fragmentary, making what remains all the more precious. The stave churches, the oldest of which date from the 12th century but are structurally indebted to Viking carpentry, carry this legacy into the Christian era. Their portals often feature dragon motifs, interlace patterns, and vegetal forms whose meaning straddles the line between pagan and Christian cosmologies. Here, the continuity of form speaks louder than the rupture of faith.

In the modern reception of Viking art, especially from the 19th century onward, much has been distorted by nationalist sentiment and romantic fantasy. The urge to reimagine the Vikings as noble ancestors of a pure Norwegian identity has sometimes led to misreadings of their art—projecting modern ideals of individuality, heroism, or even proto-democracy onto forms that were, in truth, embedded in tribal hierarchies and warrior cults. Yet when freed from such ideological weight, Viking art reveals itself as neither crude nor merely ornamental, but as a complex visual language—one that encoded myth, social order, and existential anxiety into every line.

The challenge in interpreting this early art is its ambiguity. With no texts to anchor interpretation, no artist names, and few consistent iconographies, we are left with a visual field that resists closure. But perhaps that is its truest legacy: an art that does not explain but evokes, does not narrate but invokes. It offers no single story, but an atmosphere—of tension, energy, and the ceaseless interplay between chaos and order, human and divine, craft and cosmos.

In this sense, prehistoric and Viking art form more than a prologue to Norwegian art history. They establish the foundational mode: an art tied to land and myth, modest in scale but vast in implication, and marked by a profound sensitivity to form as both ornament and ontology. From these stone carvings and wooden ships, a national aesthetic begins to emerge—not declarative or centralized, but recursive, elemental, and deeply bound to its environment. That aesthetic will reappear, again and again, across the centuries to come.

The Sacred and the Stylized: Medieval Christian Art

The Christianization of Norway in the late 10th and early 11th centuries inaugurated a profound reorientation of its visual culture. Where the Viking Age had been marked by ornamental abstraction, animistic symbolism, and a fluid integration of art into ritual and daily life, the advent of Christianity introduced new imperatives: figuration, iconography, narrative, and theological didacticism. The invisible world was no longer to be evoked through abstraction and interlace; it was to be made visible through the image of Christ, the saints, and the cosmic drama of salvation. In the process, Norwegian art began its long and sometimes uneasy engagement with continental forms—adopting and adapting the visual languages of Rome, Byzantium, and, increasingly, the monastic and ecclesiastical centers of northern Europe.

Yet this transition was not a rupture so much as a palimpsest. The first Christian artists in Norway—whether native or imported—worked within and upon the inherited visual habits of the Viking world. Nowhere is this synthesis more vividly seen than in the stave churches, Norway’s most distinctive architectural and artistic achievement of the Middle Ages. These wooden structures, of which about thirty remain today, are both architectural marvels and repositories of a hybrid aesthetic. Their soaring interiors and steeply pitched roofs conform to ecclesiastical needs, yet their carved portals and structural rhythms retain unmistakable echoes of the older pagan world.

Take, for instance, the Urnes stave church (ca. 1130), whose carved north portal is often cited as the culmination of the Viking artistic tradition in its Christianized form. Here, serpentine animals intertwine in a dynamic but controlled arabesque, recalling earlier Viking motifs while now serving the decorative scheme of a Christian building. The animals have lost their overt mythological references, but they retain an animistic charge, as if unwilling to relinquish their old powers. In this sense, the stave churches are not merely architectural structures but transitional texts—visual essays in the negotiation between two metaphysical orders.

Beyond the stave churches, medieval Christian art in Norway manifested in smaller-scale forms: painted altar frontals, crucifixes, manuscripts, liturgical objects, and reliquaries. Many of these were produced in monastic contexts, particularly after the establishment of Benedictine and Cistercian houses in the 12th century. These monasteries served as conduits of European artistic influence, importing not only theological doctrine but also stylistic norms from France, England, and Germany. Romanesque forms were particularly influential in this period, characterized by stylized drapery, frontal symmetry, and symbolic rather than naturalistic representation.

One of the most remarkable surviving examples is the altar frontal from Hedalen stave church (ca. 1250), now preserved in the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. Painted on wood, the panel depicts scenes from the Passion of Christ with a hierarchical scale, gold backgrounds, and a restrained but expressive use of color. The figures are stylized—flat, linear, and hieratic—but their gestures convey a narrative urgency that suggests the pedagogical function of such art. These were not decorative objects; they were visual sermons, designed for a largely illiterate laity. In this, Norwegian art followed the pan-European logic of Christian iconography, even as it retained a certain austerity and provincial sparseness that sets it apart from the more ornate productions of France or Italy.

The crucifixes of this era also reveal a distinctive stylistic tendency. The so-called “triumphal crucifixes,” which hung above the chancel arch in many churches, depict Christ not in agony but in majesty—eyes open, arms outstretched in a gesture of cosmic dominion. This reflects a theological emphasis on Christ as Pantocrator, ruler of the universe, rather than the later Gothic focus on his human suffering. The Gaupne crucifix (ca. 1150), with its rigid posture and stylized features, is a particularly fine example. Here again, the aesthetic is not naturalistic but emblematic: the figure is less a man than a symbol, an axis mundi between heaven and earth.

Manuscript illumination, though less developed in Norway than in England or France, nonetheless existed in a monastic context. The few surviving fragments suggest a similar Romanesque idiom: bold lines, schematic composition, and a limited but symbolically loaded color palette. More often, however, Norwegian medieval art concerned itself with the tactile and the material. Carved baptismal fonts, chalices, reliquaries, and embroidered vestments reveal a culture in which art and liturgy were inseparable. These objects were not seen in isolation; they were part of a broader sensory environment—incense, chant, candlelight—in which the divine was made present through a choreography of image and ritual.

It is important to emphasize the provincial character of much of this art. Norway in the Middle Ages was geographically isolated, politically fragmented, and economically modest. It could not support the kind of patronage systems that fueled the great cathedral-building campaigns of France or the fresco cycles of Italy. Yet this very limitation fostered a certain intimacy and restraint. Norwegian medieval art rarely aspires to monumentality; instead, it cultivates a solemn modesty, an almost monastic quietude. Its beauty lies not in opulence but in clarity—in the precision of a carved detail, the rhythm of a wooden arcade, the solemnity of a painted saint.

With the advent of Gothic art in the 13th and 14th centuries, some new elements entered the Norwegian visual vocabulary: pointed arches, more expressive figuration, and increased narrative complexity. The Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, the most ambitious ecclesiastical structure in medieval Norway, embodies this Gothic impulse. Originally begun in the Romanesque style in the 11th century, its later phases incorporated English and continental Gothic features. Its west façade, with its rows of sculpted figures, and its ornate rose window, mark it as an exceptional case in Norwegian medieval architecture—a brief flowering of grand European aspiration in an otherwise more restrained visual tradition.

The Black Death in the mid-14th century devastated Norway, reducing its population by over half and leading to cultural stagnation. Artistic production slowed considerably, and the following centuries—culminating in the union with Denmark—saw a further decline in native artistic innovation. Yet the legacy of medieval Christian art in Norway endured, both materially and spiritually. The stave churches continued to stand, silent witnesses to a bygone era; altar panels, crucifixes, and painted furnishings remained in use, gradually acquiring the patina of sacred age.

In retrospect, the medieval period in Norway represents a foundational synthesis: a time when native formal instincts—ornamental, linear, intimate—were gradually absorbed into the universalizing logic of Christian iconography. It was a period of adaptation, but not of erasure. The older visual sensibilities of the Viking world did not vanish; they were transfigured. In this, Norwegian medieval art laid the groundwork for a national aesthetic that would, centuries later, return in new guises—landscape, symbolism, abstraction—but always marked by that early fusion of the sacred and the stylized, the intimate and the cosmic.

The Long Silence: Art in the Shadow of Denmark (1536–1814)

The period between 1536 and 1814 occupies a vexed space in Norwegian art history—a span of nearly three centuries in which the country’s visual culture was, in many respects, muted. This was not a period devoid of artistic production, but one in which the structural conditions for native innovation, patronage, and institutional support were almost entirely absent. Norway, after the formal incorporation into the Danish crown in 1536 following the Reformation, ceased to function as an autonomous cultural entity. It became a subordinate province in a composite monarchy whose artistic life and court culture were centered in Copenhagen. For Norwegian art, this long union imposed a condition of political, economic, and intellectual marginalization that stifled the development of a distinctive national school.

The Protestant Reformation itself marked a dramatic rupture. With its arrival under Danish auspices in the 1530s, Norway experienced a systematic dismantling of its Catholic institutions, which had hitherto been the principal patrons of art. Monasteries were dissolved, bishops deposed, and church properties seized by the crown. The iconoclastic thrust of Lutheran theology meant that altarpieces, statues, relics, and other visual paraphernalia of Catholic worship were either destroyed or whitewashed. The great tradition of ecclesiastical painting and sculpture that had flourished during the Middle Ages was abruptly halted. What replaced it was far more utilitarian: plain wooden pulpits, modest lecterns, and the occasional didactic painting serving a strictly doctrinal function. In effect, art was reduced to a tool of moral instruction, stripped of its former ritual and aesthetic complexity.

The long-term effect of this religious and political reordering was a profound visual austerity. The church—the primary institution capable of commissioning and preserving art—no longer fostered artistic ambition. There were, to be sure, painters and craftsmen working in Norway during this time, but they were often anonymous artisans producing decorative schemes for rural churches or civic buildings, their work functional rather than inventive. Occasionally, local churches commissioned painted altarpieces or epitaphs in the Lutheran idiom, featuring scenes from the Gospels or didactic emblems of mortality. But these works were provincial in both execution and aspiration, lacking the stylistic fluency or symbolic richness of their continental counterparts.

Architecturally, the period witnessed a near-total stagnation. The stave churches remained in use, and some received minor additions or Baroque embellishments, but there were no grand ecclesiastical or civic building campaigns. The dominant material remained wood, and the stylistic vocabulary largely recycled medieval forms with occasional nods to imported Renaissance or Baroque motifs. Stone churches were rare, and urban architecture tended to be modest, practical, and ephemeral. Bergen, the principal city of western Norway, retained some Hanseatic character, but its architecture reflected trade rather than artistic ambition.

What artistic energy did exist during this period often flowed out of Norway rather than into it. Norwegian artists with ambition or talent had little choice but to travel abroad, particularly to Denmark, to seek training or commissions. A telling example is the painter and sculptor Elias Fiigenschoug (ca. 1600–ca. 1660), often regarded as Norway’s first professional artist. He was active mainly in Bergen and is best known for his 1656 painting of Halsnøy Abbey, considered the earliest known Norwegian landscape painting. While modest by European standards, it is significant as a rare instance of a native artist documenting the local environment with a degree of autonomy and aesthetic intent.

But Fiigenschoug was an exception. Most artists active in Norway during this time were either foreigners imported for specific commissions or itinerant craftsmen producing church decorations and portraiture for local elites. Many of these works exhibit a naïve charm but lack technical polish or conceptual depth. Portraits, in particular, followed a repetitive formula—stiff, frontal likenesses of clergy or bourgeois patrons, often accompanied by heraldic symbols or pious inscriptions. These were not expressions of inner psychology or stylistic experimentation; they were records of status, framed within the tight bounds of social and religious decorum.

The Danish court, meanwhile, increasingly absorbed the cultural life of the union. Copenhagen became the site of academies, royal collections, and architectural projects, all largely inaccessible to Norwegian artists or audiences. The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1754, became the principal institution for artistic education in the kingdom. For the few Norwegians who could afford to study there, it offered training in the dominant European idioms—Neoclassicism, Rococo, and later Romanticism—but their work was often assimilated into the broader Danish context. Norway, in effect, functioned as a cultural hinterland: a place from which raw materials were extracted and into which metropolitan styles were sporadically introduced, but which produced little in the way of artistic innovation on its own terms.

Yet even within this silence, one finds the slow gestation of a national consciousness. The late 18th century, under the influence of Enlightenment thought and emerging Romantic sentiment, witnessed the first stirrings of a Norwegian cultural revival. Intellectuals such as Ludvig Holberg and Gerhard Schøning began to articulate a sense of Norwegian distinctiveness rooted in history, landscape, and folklore. Though primarily literary and historical in nature, this nascent nationalism laid the groundwork for a future in which visual art would once again serve as a vehicle for identity. The idea of Norway as a land of sublime nature, moral purity, and ancient traditions would soon find pictorial expression in the Romantic landscapes of the 19th century.

The end of this long period of artistic dormancy came with geopolitical rupture. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden in 1814. Although this led to a new political union, Norway gained a constitution and a greater degree of internal autonomy than it had enjoyed under Danish rule. This political reawakening coincided with a cultural one. The silence of the previous centuries—broken only by scattered voices like Fiigenschoug—gave way to a burgeoning artistic movement that sought to define, depict, and dignify the Norwegian nation through image. The result was a national Romanticism that would, in time, produce painters of international significance and usher in a golden age of Norwegian visual art.

But to understand the full force of that emergence, one must reckon with the longue durée of deprivation that preceded it. The years between 1536 and 1814 were not merely a hiatus in artistic production; they constituted a structural absence, a cultural condition in which art was peripheral, derivative, and subordinated. It was precisely this absence—this historical deprivation—that would, paradoxically, invest the later Romantic vision with such urgency and fervor. The silence had lasted too long. The image was needed again, not as ornament or doctrine, but as revelation.

Romantic Nationalism and the Mythic Landscape (1800–1870)

The decades following Norway’s partial emancipation from Danish rule in 1814 mark a pivotal phase in its artistic history—a dramatic reawakening after centuries of dormancy. This period, stretching roughly from the early 1800s to the 1870s, witnessed the crystallization of Romantic Nationalism in the visual arts. It was not merely a stylistic moment, but a cultural project: to construct, through image, a visual identity for a nation that had been politically and artistically marginalized. This project drew on landscape, folklore, and peasant life to fashion a symbolic vocabulary through which Norwegians might recognize themselves as a people, a culture, and a coherent historical subject. The artists of this generation were not only painters; they were image-makers of a nascent nation.

Central to this emergence was Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857), widely regarded as the father of Norwegian painting. Born in Bergen, Dahl was trained in Copenhagen, but it was in Dresden—under the sway of the German Romantic landscape tradition and the influence of Caspar David Friedrich—that he developed his mature style. Yet Dahl’s significance lies not only in his artistic accomplishments but in the direction of his gaze. At a time when most Norwegian artists sought validation in cosmopolitan idioms, Dahl turned his eye homeward. He painted the fjords, the highlands, the storm-swept coasts of Norway—not as topographical records but as spiritual landscapes, charged with sublimity, history, and national allegory.

Dahl’s landscapes are neither decorative nor idealized. They resist the pastoral charm of southern European vistas and instead embrace the monumental solitude of the North. In works like View from Stalheim (1842) or Fortundalen in Lusterfjord (ca. 1840), nature is rendered with a precise observational rigor, yet always with an undercurrent of the metaphysical. These are not just scenes but invocations. Mountains rise like ancient sentinels; waterfalls fall like sacramental veils. The land becomes both stage and subject, a repository of memory and identity. In this, Dahl achieved what no Norwegian artist before him had done: he made the national landscape legible as a historical and emotional document.

Crucially, Dahl’s Romanticism was not escapist. Though often celebrated for his spiritual reverence for nature, Dahl was also a civic-minded intellectual. He advocated for the preservation of Norwegian cultural heritage, including stave churches and medieval monuments, and was instrumental in founding the National Gallery in Oslo. His art and his activism were intertwined; both sought to articulate a Norwegian essence that was more than administrative or territorial—it was cultural, spiritual, and rooted in place.

The power of landscape as a vehicle of national sentiment extended beyond Dahl. Thomas Fearnley (1802–1842), a student of Dahl, brought a slightly different sensibility to the genre. While Dahl’s work often emphasized the mystical grandeur of the land, Fearnley introduced a more dynamic, observational realism. His travels through the Alps, Italy, and Germany informed his compositional strategies, but it was in Norway that his most poignant works were realized. Paintings such as Labrofossen (1837) or Grindelwald Glacier (1838) convey a physical immediacy—a sense of being in the midst of geological time. Fearnley’s technique was more fluid than Dahl’s, more concerned with atmospheric effects and the ephemerality of light, but his subject matter remained firmly tied to the Romantic belief in nature as a mirror of national character.

Norwegian Romanticism did not limit itself to landscape. The broader cultural project encompassed genre painting, historical scenes, and, above all, the visualization of folklore. The idea of the “folk”—rural peasants, mountain dwellers, bearers of oral tradition—became central to the Romantic imagination. In this, painters found kinship with writers like Henrik Wergeland and Peter Christen Asbjørnsen, whose compilations of Norwegian folktales gave artists a trove of mythic imagery and rustic archetypes. These stories of trolls, wood spirits, and heroic farmers offered a symbolic counter-narrative to the cosmopolitan culture of Denmark and Sweden. They rendered Norwegian identity as ancient, indigenous, and organically tied to the land.

Artists such as Adolph Tidemand (1814–1876) and Hans Gude (1825–1903) epitomized this union of folklore and landscape. Their most famous collaboration, Bridal Procession on the Hardangerfjord (1848), is a seminal work in the Romantic Nationalist canon. The painting depicts a traditional wedding scene, with a rowing boat bearing the bride and her entourage across a sunlit fjord, flanked by craggy peaks and shimmering waters. Every detail—the costumes, the boat, the surrounding landscape—is rendered with ethnographic precision, yet the overall effect is idealized, almost mythic. It is an image of Norway not as it was, but as it needed to be seen: unified, beautiful, timeless.

Tidemand’s solo work often focused on peasant interiors and rural customs. His paintings, such as Haugianerne (The Haugeans, 1852), present religious and domestic life among Norway’s pietistic communities with solemn dignity. These were not sentimental depictions but attempts to monumentalize the ordinary, to show the moral seriousness and cultural depth of Norway’s rural classes. In doing so, Tidemand positioned the peasant not as a curiosity but as a bearer of national continuity.

Meanwhile, Hans Gude continued to develop the Romantic landscape, particularly in his later years, when he turned to scenes of coastal life and seafaring. His treatment of light and atmosphere, especially in paintings such as Coast of Norway (1870s), brought a refined luminosity to the tradition. Gude was also a significant teacher, influencing later generations of Norwegian painters and helping institutionalize landscape painting within the curriculum of the newly founded art academies.

It is worth noting that Romantic Nationalism in Norway was not an insular phenomenon. It participated in and responded to broader European currents, particularly the Romantic valorization of nature, the rise of historical consciousness, and the Romantic belief in art as a vehicle for cultural renewal. Yet its specific inflection in Norway—shaped by political history, geographic isolation, and cultural marginality—produced a version of Romanticism more austere, more elemental, and more ethnographic than that of Germany or France.

There is, too, a melancholic undercurrent in Norwegian Romantic art—a recognition that the very world it seeks to immortalize is vanishing. The fjords remain, but the folk traditions, the rural customs, the religious fervor of the peasants are already fading. The paintings of this era are thus tinged with elegy. They do not merely celebrate a national essence; they mourn its disappearance. In this, they anticipate the Symbolist and Expressionist tones of the next generation, particularly in the work of Edvard Munch.

By 1870, the visual vocabulary of Norwegian nationalism had been firmly established. Landscape, folklore, peasant life—these became the pillars of a cultural identity that had once seemed intangible. Through the brush of Dahl, Fearnley, Tidemand, Gude, and others, Norway had found a way to see itself, to believe in itself, and to assert its presence in a Europe where it had long been absent from the cultural map. It was a triumph not merely of art but of imagination—a visual nation conjured from mountains, myths, and memory.

Christian Krohg and the Realist Gaze

By the final decades of the 19th century, the poetic certainties of Romantic Nationalism began to fracture under the pressure of modernity. Industrialization, urban migration, secularism, and the rise of scientific rationalism challenged the aesthetic and moral foundations of the Romantic tradition. The sublime landscapes and folkloric tableaux that had once embodied national identity began to feel increasingly anachronistic—nostalgic projections rather than reflections of contemporary life. Into this space entered a new generation of artists who rejected the idealized past in favor of the visible present, and who saw in realism not a mere style, but a moral imperative. Among them, Christian Krohg (1852–1925) stands as a transformative figure: a painter, writer, journalist, and social critic whose work dismantled the sentimental illusions of Norwegian Romanticism and replaced them with a hard-eyed, compassionate gaze.

Krohg’s realism was not imported wholesale from France or Germany; it was rooted in the specificities of the Norwegian experience, even as it engaged European artistic currents. Trained initially in law, Krohg abandoned the profession to study painting in Karlsruhe and later in Berlin under Karl Gussow, and he absorbed the influence of the French realists and naturalists—particularly Gustave Courbet and Jules Bastien-Lepage. But unlike the academicians who sought technical perfection within traditional genres, or the Symbolists who turned inward, Krohg was drawn to the contemporary world: its injustices, its dramas, its unsentimental textures. His subjects were not fjords or peasants in national dress, but prostitutes, sailors, beggars, factory workers, and unwed mothers. He was, in this respect, both a realist and a radical.

The defining example of Krohg’s ethos is his painting Albertine i politilægens venteværelse (Albertine in the Police Doctor’s Waiting Room, 1887). It depicts a young woman—Albertine—awaiting a compulsory medical examination after being suspected of prostitution. She sits in a dreary, impersonal room, surrounded by other women whose expressions range from weariness to defiance. There is no overt drama, no melodrama—only the heavy weight of social circumstance. The composition is frontal, static, and oppressive. Every detail—the sterile furnishings, the closed door, the bored indifference of the officialdom—conveys institutional control. What shocks is not what is shown, but what is made visible: the bureaucratic mechanisms that dehumanize the vulnerable.

The painting was inspired by Krohg’s own novella Albertine (1886), which caused a national scandal upon publication and was immediately confiscated by the authorities for its frank portrayal of sexual exploitation and moral hypocrisy. The controversy only intensified with the painting’s exhibition, prompting debates in the press and the Storting (Norwegian parliament) about public morality, prostitution, and censorship. Krohg had not only painted a scene; he had punctured the comfortable illusions of bourgeois society. His work revealed how art, in the realist mode, could act as a form of social interrogation.

Yet Krohg was never a propagandist. His realism is deeply humanist, even when unflinching. In Sick Girl (1881), a portrait of a frail child with sunken eyes and pale skin, the rendering is stark, but not voyeuristic. The figure is painted with tenderness, her vulnerability dignified rather than exposed. Likewise, in Sleeping Mother with Child (1883), the exhausted body of the mother is given monumental presence, her limp arm and heavy brow speaking of both labor and love. These paintings resist sentimentality even as they honor their subjects. They insist on the significance of the ordinary, the dispossessed, the marginal.

Krohg’s maritime scenes also exemplify this ethos. In works such as Fishermen at Sea (ca. 1880s), the sea is not a sublime Romantic backdrop but a space of labor and risk. The fishermen are not idealized types; they are specific, individualized figures whose weathered faces and stoic bearing testify to the hardships of coastal life. The brushwork is loose but controlled, the palette dominated by greys, blues, and ochres—a far cry from the sunlit fjords of Gude and Tidemand. The sea is neither mythic nor allegorical; it is real, cold, dangerous, and indispensable. In this, Krohg’s art reconnects with one of the deepest currents in Norwegian visual culture: the intersection of labor, land, and dignity.

As a writer and editor, Krohg also played a crucial role in shaping Norwegian cultural life. He was a contributor to Verdens Gang, one of Norway’s most influential liberal newspapers, and later edited the literary journal Impressionisten, which promoted new art and literature. His polemics and essays championed the cause of naturalism, freedom of expression, and social reform. His advocacy helped loosen the grip of academic conservatism on Norwegian institutions and opened space for more diverse and experimental voices in the arts.

Krohg was also a pivotal figure in education. In 1894, he co-founded the Kristiania Bohemian Circle along with Hans Jæger and other radicals who sought to challenge the norms of Norwegian bourgeois life. Though the group was short-lived and often caricatured, its emphasis on personal freedom, sexual emancipation, and anti-authoritarianism found echoes in Krohg’s later work. In 1909, he was appointed director of the Norwegian Academy of Fine Arts, where he sought to modernize the curriculum and encourage individuality rather than conformity. His influence on the next generation of artists—many of whom would embrace Impressionism, Expressionism, or Symbolism—was profound.

It is tempting to cast Krohg as a purely oppositional figure, but this would be reductive. While he rejected the sentimentality of Romanticism and the abstraction of Symbolism, he did not scorn tradition. Rather, he reoriented it. Where the Romantics saw nature as a mirror of the national soul, Krohg saw society as a crucible of moral truth. Where earlier painters idealized the folk, Krohg dignified the contemporary. His art extended the national project of the 19th century, but turned it inward—toward the city, the body, the overlooked. In this, he bridged the Romantic and the modern, the national and the individual, the aesthetic and the ethical.

In retrospect, Krohg’s legacy lies not in any single stylistic innovation but in the seriousness with which he approached the question of what art could be—and for whom it could speak. He redefined the painter not as an interpreter of myths or a servant of taste, but as a witness, a critic, and at times a conscience. His gaze was not merely realistic; it was revelatory.

The Visionary Solitude of Edvard Munch

Among the many paradoxes that define the history of Norwegian art, perhaps none is greater than the global centrality of Edvard Munch (1863–1944) within a tradition so often characterized by its peripheral solitude. Munch is both utterly Norwegian and resolutely transnational, a modernist whose singular vision emerged not despite his cultural context but, in many ways, because of it. His life spanned two centuries and numerous upheavals: the dissolution of union with Sweden, the rise of psychological science, the trauma of war, and the dawn of Expressionism. In this matrix, Munch produced an art that was at once subjective and universal, deeply personal yet emblematic of modern anxiety itself. He did not merely document reality—he transformed it into psychological myth.

To understand Munch’s development is to recognize how profoundly he was shaped by death, illness, and familial trauma. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was five; his beloved sister Sophie succumbed to the same disease a few years later. His father, a deeply religious man prone to melancholy, instilled in Munch a lifelong awareness of spiritual dread. These biographical shadows are not peripheral—they are the substrate of his entire artistic project. For Munch, art was not decoration or documentation, but exorcism. “I do not paint what I see, but what I saw,” he once wrote, indicating a rupture between objective perception and inner vision that would become the hallmark of his style.

Munch’s early works bear the influence of Norwegian Naturalism, particularly the social realism of Christian Krohg, under whom he briefly studied. His early masterpiece The Sick Child (1885–86) marks the point of departure. It depicts the deathbed of his sister Sophie, her pale figure fading into an ethereal background, as an older woman (perhaps his aunt Karen) bows in mourning beside her. The brushwork is loose, the forms indistinct, the surface almost abrasively rough. Upon its exhibition, it was met with confusion and hostility—accused of incompetence, sentimentality, and ugliness. Yet this reception misunderstood the painting’s core innovation: it was not attempting to illustrate an event, but to externalize a grief that could not be fully expressed in language or form. In this sense, it inaugurates the Symbolist strain in Munch’s oeuvre, in which personal memory and psychic intensity override visual coherence.

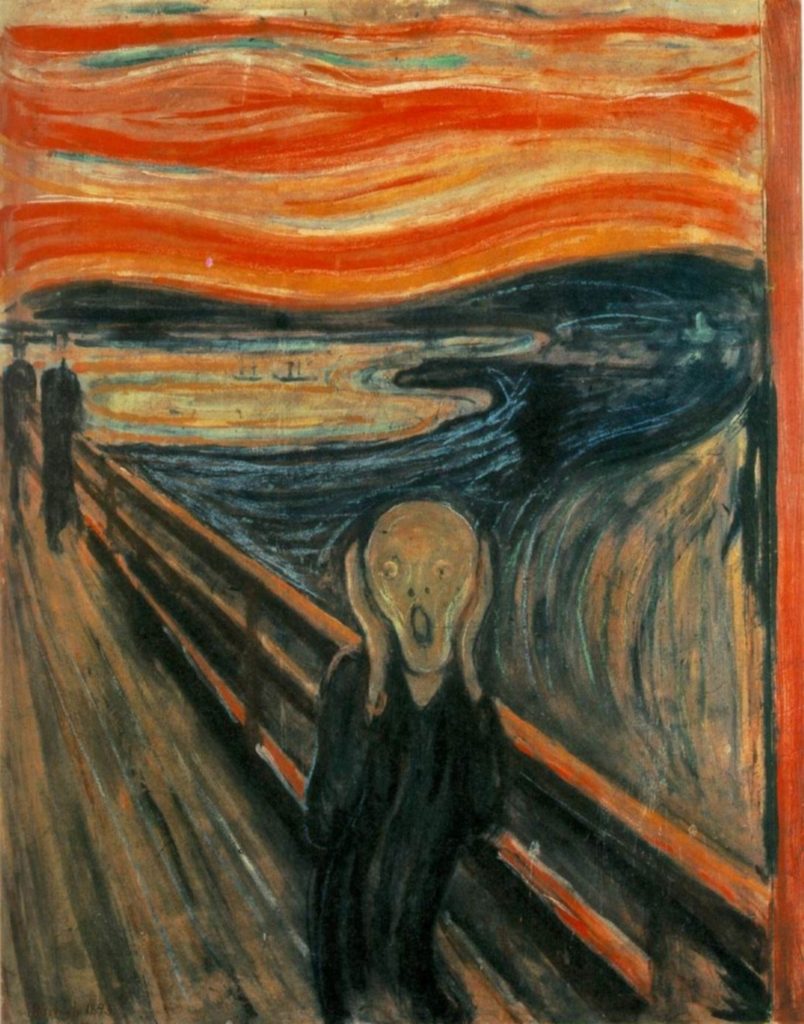

By the early 1890s, Munch had moved to Berlin and immersed himself in the European avant-garde. It was here that he produced the first works in what would become his Frieze of Life—a thematically unified series exploring love, anxiety, jealousy, sickness, and death. These paintings were not conceived as separate works but as variations on a metaphysical theme. Among them are his most iconic images: The Scream, Madonna, The Dance of Life, and Ashes. In these, Munch achieved a synthesis of symbol and expression, abstraction and narrative. The forms are often distorted, the colors exaggerated, the compositions charged with psychological tension. This was not realism in any recognizable sense, but a new kind of interior figuration—what would soon be termed Expressionism.

The Scream (1893), perhaps the most famous painting ever produced by a Norwegian artist, transcends its national origins to become a universal emblem of existential dread. Yet its genesis is profoundly local. Munch described the inspiration as a moment of panic experienced while walking along a fjord near Oslo (then Kristiania), when the sky turned red and he “felt a great, infinite scream pass through nature.” The painting’s sinuous lines, blood-colored sky, and hollow-eyed figure distill that moment into an image of pure psychic rupture. The figure is not screaming, but hearing the scream of the universe—a subtle yet crucial distinction. The scream is not located in the body, but in the air, in the landscape, in being itself.

In Madonna (1894–95), Munch reconceives the Virgin not as a vessel of purity but as a figure of erotic mysticism—eyes closed, head tilted, arms raised in surrender or ecstasy. The black halo and swirling background suggest both sanctity and sensuality. Beneath her, in some versions, sperm and a fetus spiral through the frame—a mingling of creation and decay, sanctity and sin. Here, Munch confronts the religious icon with the Freudian unconscious, collapsing the categories of sacred and profane. This iconoclasm was not blasphemous so much as metaphysical, driven by a desire to expose the psychic contradictions of modern identity.

Throughout the Frieze of Life, certain compositional devices recur: flattened perspectives, exaggerated silhouettes, recursive motifs, and unnatural color schemes. These formal choices were not decorative but expressive, designed to convey affect rather than mimesis. In The Dance of Life (1899–1900), Munch presents the life cycle through a trio of female figures: a virginal woman in white, a passionate woman in red, and a mourner in black. Between them, couples dance under the moonlight, caught in a ritual of desire and loss. The painting is theatrical, even choreographic, but its rhythms are funereal. Life, Munch suggests, is a dance shadowed by death.

Munch’s influence on German Expressionism is incalculable. His exhibitions in Berlin and Prague in the early 20th century shaped the aesthetics of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, even as he remained personally aloof from these movements. His art offered a model for how the self could be rendered without illusion—raw, fractured, vulnerable. At a time when academic art still clung to classical decorum, Munch tore open the canvas and exposed the nerves beneath. He also prefigured much of what would come later in 20th-century art: the psychological intensity of Francis Bacon, the symbolic spatiality of Mark Rothko, the existential solitude of Giacometti. In this sense, he was not merely a Norwegian painter but a prophet of modern disintegration.

Yet Munch never entirely severed his ties with Norway. He returned repeatedly to his homeland, eventually settling in Ekely, near Oslo, where he continued to paint until his death in 1944. His later works are often overlooked, but they are vital. During the interwar years, he produced numerous self-portraits, landscapes, and images of workers and farmers. His brushwork became looser, his colors more muted, his forms increasingly abstract. These paintings lack the tortured lyricism of the Frieze but possess a quiet authority—a kind of metaphysical realism that situates the self within the broader cycles of nature and labor. In Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed (1940–43), Munch confronts his own mortality with a calm, even stoic gaze, flanked by two icons of inevitability: time and sleep. It is one of the most haunting self-portraits in Western art.

Munch’s posthumous reception in Norway has been ambivalent. Though now enshrined as the country’s greatest artist, his career long challenged national sensibilities. He was accused of morbidity, obscenity, madness—his psychological subject matter clashing with the wholesome image of Norway as a land of purity and harmony. But time has vindicated him. Today, the Munch Museum in Oslo houses the largest collection of his works, and his legacy informs generations of Norwegian and international artists who seek to translate inner life into form.

In Munch, the trajectory of Norwegian art reaches a kind of apotheosis. He synthesized the Romantic landscape, the Realist concern with the human condition, and the Symbolist drive toward interiority. He turned the Norwegian sensibility—its melancholy, its mysticism, its intimacy with nature—into a universal idiom. His vision was solitary, even alienating, yet it resonates across borders. He did not simply depict anxiety; he embodied it, gave it shape and color and scream. In doing so, he made visible what had long been unspoken: the abyss at the heart of modern life.

Art in the Nation-Building Era: 1905 and Beyond

The dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905 was a moment of profound symbolic and political redefinition for Norway. After centuries of subordination—first under Denmark, then Sweden—the country emerged into the 20th century with full sovereignty. This transformation was not merely constitutional; it marked the beginning of an intensified cultural self-fashioning in which the arts, and especially visual art, assumed a pivotal role. The challenge was now to construct a visual language that could affirm national identity without lapsing into folkloric repetition, and to integrate modern artistic developments into a tradition that had been rooted in Romantic idealization and rural nostalgia. The period between 1905 and the interwar years thus became a laboratory for new artistic directions, tensions, and syntheses—a moment when the nation sought to see itself anew.

In the immediate aftermath of independence, the cultural climate remained imbued with the residue of Romantic Nationalism. Yet the tone was shifting. The grandeur of the fjord and the moral purity of the peasant were no longer sufficient emblems of modern identity. Urbanization, industrial development, and the rise of a politically conscious working class demanded new subjects and new forms. Artists now had to reckon with a society in flux: rural life coexisted uneasily with modern cities, and traditionalism vied with avant-garde impulses.

At the heart of this transition was a desire to institutionalize Norwegian art in a way that would stabilize its newfound national status. The founding of the National Gallery in Oslo (previously Kristiania) and the expansion of art schools, exhibitions, and state patronage programs created a more structured environment for artistic production. The government saw cultural investment as a necessary complement to political sovereignty: to be a modern nation was not only to possess borders and laws, but to cultivate a national consciousness through image, architecture, and public monument.

This ethos found expression in the growing importance of public art. Statues of historical figures, murals in public buildings, and decorative programs in new civic spaces proliferated. The sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869–1943) became the leading figure in this arena, transforming Oslo’s urban landscape with an ambitious program of monumental sculpture. His magnum opus, the Vigeland Installation in Frogner Park, is perhaps the most iconic example of this nationalist monumentalism. Comprising over 200 granite and bronze figures arranged in symbolic ensembles, it is a cosmological narrative rendered in flesh: scenes of birth, struggle, embrace, death, and eternity unfold in a spiral composition culminating in the towering Monolith, a column of interwoven human bodies. Vigeland’s work eschews realism in favor of allegory, but it retains a distinctly Nordic gravitas—stoic, corporeal, and metaphysical.

Though often criticized for its grandiosity or conservative symbolism, the Vigeland complex reflects a core aspiration of the post-1905 moment: to inscribe the human condition into public space in a way that affirms both collective destiny and national uniqueness. Vigeland did not depict Norwegians per se, but rather universal archetypes seen through a Scandinavian lens. His figures are monumental yet intimate, expressive without sentimentality—modern in their psychological intensity, ancient in their sculptural language.

Other artists sought to capture the changing realities of Norwegian life through more subdued, observational means. Harriet Backer (1845–1932), though trained earlier, produced some of her most mature work in this period, continuing to depict domestic interiors and quiet moments of contemplation with luminous precision. Her restrained palette and attention to light reveal a painter deeply attuned to mood and atmosphere, yet her subjects—middle-class women, children, and the aging—reflect the new complexities of gender and modernity. Backer’s work stands as a bridge between 19th-century intimacy and 20th-century introspection.

Meanwhile, a new generation of painters emerged, eager to shed the last vestiges of Romanticism. Halfdan Egedius, Thorvald Erichsen, and Ludvig Karsten began experimenting with color, composition, and brushwork in ways that anticipated both Post-Impressionism and Expressionism. Karsten in particular developed a vivid, gestural style that often verged on abstraction, especially in his later landscapes and still lifes. His embrace of spontaneity and materiality placed him at odds with academic norms, but it also signaled the arrival of a more Europeanized modernism within Norwegian art.

It is important to note that the 1905 generation did not reject tradition wholesale. Rather, they reinterpreted it. Norwegian history, landscape, and folklore remained important, but were now treated as sources of formal experimentation or psychological resonance rather than nationalist affirmation. The best artists of the period moved beyond illustration into a more introspective mode, using national motifs to explore universal concerns. In this, they mirrored developments in literature, where figures like Knut Hamsun and Sigrid Undset grappled with the contradictions of modern identity through complex, often ambivalent narratives of place and self.

The post-1905 years also saw the institutionalization of artistic education and criticism. The establishment of the Norwegian National Academy of Fine Arts provided a formalized structure for training, while journals, salons, and critics helped shape public discourse. Artistic debates now concerned not only subject matter but form, theory, and technique. This professionalization was double-edged: it lent Norwegian art a new visibility and coherence, but it also introduced new hierarchies and exclusions, often marginalizing unorthodox or regional voices in favor of a central canon.

Nonetheless, the period was marked by pluralism. Naturalism, Symbolism, Impressionism, and emerging forms of abstraction coexisted, often within the work of a single artist. This stylistic diversity reflected the tensions of a society in transition, as well as the unresolved question of what it meant to be Norwegian in a globalizing world. Could national identity be grounded in form rather than content? Could art be modern without being cosmopolitan? These were not merely aesthetic questions; they were existential.

The First World War, though Norway remained officially neutral, deepened these tensions. The war underscored the fragility of European civilization and exposed the moral limits of idealist art. In its wake, Norwegian artists—like their counterparts across Europe—gravitated toward fragmentation, irony, and psychological depth. Yet even as internationalism intensified, Norway retained a distinct visual idiom: cool, luminous, and emotionally restrained. This tone, often misread as aloofness, is in fact a legacy of the very landscape and cultural solitude that had shaped Norwegian art since the beginning.

By the late 1920s, the generation that had come of age around 1905 began to recede, making way for a more radical modernism that would fully emerge in the interwar period. But their legacy was decisive. They had redefined Norwegian art not as a nostalgic return to roots, but as a forward-looking engagement with identity, form, and community. They had created institutions, challenged conventions, and produced works that still anchor the national canon. Most importantly, they had proven that in the wake of political independence, cultural independence—though more elusive—was not beyond reach.

In sum, the art of the nation-building era was marked by ambition tempered with introspection, by innovation grounded in memory. It was not revolutionary in the Parisian sense, but it was transformative. It gave Norway a new mirror—one that reflected not an ideal, but a self-in-process.

Between Tradition and Experiment: Interwar and WWII-era Art

The interwar period in Norway (1918–1940) was a time of aesthetic reckoning, social transformation, and deep ideological ambivalence. The traumas of World War I, though Norway remained officially neutral, reverberated through its cultural institutions. The optimism and constructive nationalism of the post-1905 period gave way to a more fragmented, anxious mood. Artists now grappled with modernism not as a style to be cautiously integrated into the national canon, but as a set of radical propositions that questioned the very grounds of perception, identity, and tradition. Yet this openness to experiment was checked by powerful countercurrents: regionalism, traditionalism, and the rise of ideological politics. The interwar years thus produced a Norwegian art scene in tension—a dynamic, often contradictory field in which the competing demands of nation, modernity, and morality could not be easily reconciled.

This period saw the further maturation of artists who had begun their careers before World War I but now found themselves redefined by a new cultural atmosphere. One of the most emblematic figures of this transition was Ludvig Karsten (1876–1926), whose expressive, impasto-laden brushwork and emotionally volatile subject matter aligned him more closely with French Post-Impressionism and German Expressionism than with the decorous traditions of earlier Norwegian painting. In works like The Blue Kitchen (1913) or Self-Portrait with a Yellow Hat (1915), Karsten combined raw materiality with psychological acuity, pushing the expressive capacities of color and gesture. His tragic, self-destructive life mirrored the restlessness of his canvases, and his premature death in 1926 marked the end of a particularly bold strain of Norwegian painterly modernism.

In parallel, a new generation began to emerge—artists born at the end of the 19th century who were shaped by both domestic traditions and international exposure. Ragnhild Keyser (1889–1943), for instance, spent significant time in Paris, absorbing the lessons of Cubism and abstraction. Her compositions, such as Composition (Woman with a Mandolin) (ca. 1927), demonstrate a sophisticated command of form and a cool, structural clarity that placed her within the orbit of European modernism. Yet Keyser’s work remained little known in Norway during her lifetime, reflecting the challenges faced by women artists and by abstraction more generally in a country still ambivalent about radical formalism.

The 1920s and 1930s were also a time of significant institutional expansion. New exhibition spaces, art schools, and journals proliferated, giving Norwegian artists greater access to international discourse. The Artists’ House (Kunstnernes Hus), which opened in 1930 in Oslo, became a focal point for avant-garde exhibitions, debates, and manifestos. Yet even as artists debated the merits of abstraction, surrealism, and functionalism, there remained a persistent pull toward localism and figuration. Many artists sought to forge a “middle way”—neither academic nor avant-garde, but modern in a restrained, national idiom. This middle ground was often occupied by artists like Jean Heiberg, Axel Revold, and Per Krohg (son of Christian Krohg), who experimented with modernist techniques while maintaining legibility and symbolic content.

Per Krohg (1889–1965) offers a particularly instructive case. Trained in Paris under Matisse, Krohg brought a decorative, linear style back to Norway and applied it to a wide range of formats: easel painting, illustration, public murals. His works often feature allegorical or mythological subjects rendered in a vivid, accessible style. As a public artist, he was instrumental in creating a visual language for the emerging welfare state, culminating in his monumental murals for the United Nations Security Council Chamber in New York (1952). But even in the interwar years, his work embodied the attempt to reconcile modern form with collective address—to produce a public modernism.

The political polarization of the 1930s, however, made such reconciliations increasingly difficult. The rise of fascist movements in Europe, the growing appeal of Marxism among intellectuals, and the economic ravages of the Great Depression all placed new demands on artists. Should art be autonomous or engaged? Should it reflect the inner world or intervene in the outer one? In Norway, this debate took on a particular urgency given the nation’s recent independence and its vulnerable position between great powers. Many artists aligned themselves with leftist movements, contributing to workers’ publications and using their art to critique inequality. Others, particularly those drawn to classical forms or anti-modernist aesthetics, veered rightward, seeing in fascist rhetoric a promise of order and renewal.

One of the most disturbing consequences of this ideological polarization was the cultural complicity that emerged during the German occupation of Norway (1940–1945). When National Socialist forces invaded and occupied the country in April 1940, Norwegian art faced a profound crisis. Some artists collaborated with the occupiers, joining the Nasjonal Samling (Norwegian fascist party) and producing propagandistic works that glorified Nordic heritage, militarized masculinity, or the cult of the leader. Others resisted, going underground or ceasing to exhibit altogether. The occupation created a cultural bifurcation that would cast a long shadow over postwar debates about morality, collaboration, and artistic integrity.

Yet even in this dark period, there were moments of quiet resistance and formal achievement. Kai Fjell (1907–1989), for example, developed a symbolist style that drew on Norwegian folk art, medieval Christian motifs, and early modernist painting. His works from the 1940s, such as Mother and Child (1943), are dense with private iconography—figures suspended in dreamlike spaces, rendered in a palette of muted reds, ochres, and greens. Fjell’s art did not engage politics directly, but its retreat into an inner world can be read as a refusal of fascist spectacle and ideological clarity. In this, it offered a different kind of resistance: a reclamation of ambiguity, privacy, and poetic freedom.

Another significant figure of the occupation period was Reidar Aulie (1904–1977), a committed socialist whose paintings and drawings documented the suffering and resilience of the working class. His graphic, sometimes brutal style drew on German Expressionism, but his subject matter remained rooted in Norwegian social realities. Aulie’s work served as both witness and protest, and his postwar reputation would rest in part on this moral clarity. Yet even he recognized the limits of didacticism; his later works move toward a more symbolic and introspective tone, suggesting that the trauma of occupation left no easy answers.

The end of World War II brought with it both relief and reckoning. The cultural purges that followed the liberation sought to identify and punish collaborators, but they also exposed the complexities of artistic survival under authoritarian regimes. Some artists had equivocated; others had adapted out of necessity; a few had resisted at great personal cost. The occupation had made clear that art could no longer be thought of as apolitical or detached. Its meanings were now inextricably bound to history, ideology, and responsibility.

In retrospect, the interwar and World War II periods represent a crucible for Norwegian art. They were years of intense experimentation and equally intense anxiety, of new freedoms and new constraints. Artists stretched the limits of form, debated the role of politics, and faced the moral demands of history. The results were mixed, often contradictory, but deeply formative. This was a generation that had inherited the myths of Romanticism and the certainties of national independence, only to find themselves in a world of instability, irony, and rupture.

What emerged from this crucible was not a coherent movement, but a heightened awareness: of art’s power, its vulnerability, and its inescapable entanglement with the world. Norwegian art had entered the modern condition—not as a triumph, but as a reckoning.

Postwar Modernism and State Patronage

The aftermath of World War II ushered in a new era for Norwegian art, shaped by the simultaneous forces of reconstruction, ideological realignment, and modernist aspiration. The occupation years had left both material devastation and moral ambiguity in their wake. Norway, like much of Europe, faced the challenge of rebuilding not only its infrastructure but its cultural institutions, public trust, and collective narrative. In this context, the state emerged as the principal patron of the arts—a role that would deeply influence the direction of postwar modernism in Norway. Art was no longer simply a private pursuit or an elite preoccupation; it was reimagined as a public good, a democratic right, and a tool of cultural renewal.

This transformation was institutional as much as aesthetic. The Arts Council Norway (Norsk kulturråd) was established in 1965, but its philosophical foundations were laid in the immediate postwar years, when successive governments began to promote culture as a pillar of the modern welfare state. This vision was rooted in social democratic ideals: equality of access, support for regional diversity, and an emphasis on education. Art was to be decentralized, demystified, and integrated into everyday life. Museums expanded, public commissions proliferated, and artists received stipends and grants designed to insulate them from the whims of the market. It was an ambitious experiment in cultural infrastructure—and one that profoundly shaped the character of Norwegian modernism.

Yet the stylistic shape of postwar Norwegian art was not dictated by ideology. Rather, it emerged through a set of convergences: between European modernist movements and local traditions, between individual innovation and collective institutions. The war had fractured the historical continuity of art; now the task was to reassemble it in new forms.

In the 1950s and 1960s, abstraction came to dominate Norwegian painting, driven in part by international trends and in part by a generational desire to break with the figurative, moralizing tendencies of the interwar years. This was not the heroic abstraction of American Abstract Expressionism, but a cooler, more deliberate exploration of form, texture, and material. Norwegian artists engaged with the language of modernism not as a revolutionary rupture but as a process of refinement and distillation.

A central figure in this turn was Jakob Weidemann (1923–2001), whose early works reflected Expressionist influences but soon evolved into a lyrical abstraction characterized by vibrant color, organic forms, and a sense of visual rhythm. In works such as Storfuglen letter (The Capercaillie Takes Off) (1959), Weidemann melded gestural brushwork with suggestive references to landscape and flora, creating paintings that hover between the purely formal and the symbolically evocative. His use of color was especially radical within a Nordic context—bold reds, blues, and yellows deployed with a freedom that resisted the subdued tonalities of earlier national traditions. Weidemann became a key figure in shaping the visual identity of the postwar period, not least through his contributions to public art and education.

Alongside Weidemann, other abstract painters such as Inger Sitter, Ludvig Eikaas, and Erling Enger developed highly individual approaches to form. Sitter, one of the few prominent female modernists of her generation, combined geometric rigor with expressive energy, producing works that reflected both international modernist dialogues and a personal, intuitive sensibility. Eikaas, more eclectic, veered between abstraction, satire, and figuration, while Enger remained closer to the emotional textures of Expressionism.

Sculpture, too, underwent a major transformation. The generation that followed Gustav Vigeland turned away from allegory and monumentality toward more experimental and often minimal forms. Knut Steen (1924–2011), though initially trained in a realist idiom, moved toward abstraction in stone and bronze, exploring the expressive possibilities of surface, void, and rhythm. His later works, often installed in public spaces, reflect the belief that sculpture could serve as a meditative counterpoint to the built environment—a kind of secular totemism. Other sculptors, such as Arnold Haukeland, embraced welded steel and industrial materials, creating dynamic, open structures that redefined the relationship between art and space.

What distinguished postwar Norwegian modernism from its European and American counterparts was its deep entanglement with the state. This was not art for art’s sake, nor was it entirely subsumed into political messaging. It existed in a kind of third space: publicly supported, but artistically autonomous; ideologically neutral, but socially embedded. The state did not dictate style, but it did create conditions of possibility—grant programs, procurement policies, and institutional networks that encouraged experimentation without commercial dependency. This paradoxical structure produced a modernism that was both rigorous and modest, ambitious yet untheatrical.

This ethos was most visibly realized in the architecture and public art of the postwar decades. The rebuilding of towns and cities offered artists opportunities to integrate their work into new civic environments—libraries, schools, government buildings, and hospitals. Murals, tapestries, reliefs, and site-specific installations became part of the visual fabric of daily life. Artists such as Hannah Ryggen, a Swedish-born textile artist who lived in rural Norway, used weaving to comment on political and ethical questions, combining modernist formalism with folk techniques and potent symbolism. Her tapestries, including those exhibited at the 1937 Paris Exposition and later the United Nations, exemplify the synthesis of local craft and international critique.

Meanwhile, the art academies and critics fostered an increasingly international orientation. Young artists traveled to Paris, New York, and Berlin, bringing back influences from Tachisme, Informel, and later Pop Art and Conceptualism. Yet even as these styles entered the Norwegian lexicon, they were often filtered through a characteristically Nordic sensibility: cool, contemplative, and resistant to spectacle. The embrace of modernism did not entail the rejection of landscape, myth, or memory—it involved their sublimation into new forms.

Photography also began to assert itself as a serious artistic medium in this period, with figures like Kåre Kivijärvi pioneering a form of documentary photography that transcended reportage. His stark, black-and-white images of northern Norway—windswept plains, fishermen at sea, Sami reindeer herders—combined formal elegance with ethnographic attention. They extended the tradition of landscape art into a photographic idiom, emphasizing texture, atmosphere, and the human scale of survival.

By the late 1960s, the mood began to shift once again. Student protests, the rise of feminism, and new critiques of institutional authority challenged the consensus of the welfare-state modernism that had dominated the previous two decades. Some artists began to question the very frameworks—national galleries, academies, procurement policies—that had nurtured their work. Others turned toward more conceptual, ephemeral, or participatory practices. But the groundwork laid in the postwar years remained durable: a belief in the public value of art, the legitimacy of abstraction, and the necessity of artistic autonomy within a shared social compact.

In hindsight, postwar modernism in Norway was less a break than a recalibration. It absorbed the shocks of war, the lessons of international innovation, and the pressures of democratic culture, producing a visual language that was both rooted and expansive. It may not have produced global superstars or market spectacles, but it cultivated something more rare: a sustained, publicly supported engagement with modernity that treated art as a vital, evolving part of civic life.

Land Art, Environment, and the Aesthetics of Place

Among the most distinctive threads in Norway’s modern and contemporary visual culture is its deep entanglement with the land—not merely as subject matter, but as medium, metaphor, and site of artistic intervention. This tendency, which emerges most forcefully in the 1970s and develops through to the present day, aligns in part with the international Land Art movement, yet it diverges in tone, method, and meaning. Where American Land Art, exemplified by Robert Smithson or Michael Heizer, often emphasized monumental gestures, remote deserts, and the sublime scale of the continental void, Norwegian approaches have been smaller in scale, more intimate, and more ethically entwined with questions of ecology, sustainability, and historical memory. In Norway, the land is not an abstract canvas—it is a lived, storied, and often contested field of experience.

The preconditions for this artistic evolution are both cultural and geographical. Norway’s landscape has long been central to its national mythology, from the Romantic sublime of the 19th century to the modernist landscape abstractions of the postwar era. But beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a younger generation of artists began to reconfigure this relationship. No longer content to depict or evoke nature, they sought to enter into a direct dialogue with it—shaping, altering, documenting, or inhabiting natural spaces as acts of artistic creation. These interventions were often modest, temporal, and site-specific, challenging both the commercial art market and the traditional definitions of sculpture and installation.

A seminal figure in this context is Kjell Erik Killi-Olsen (b. 1952), whose work, while often located within gallery spaces, embodies a sensibility that fuses landscape, mythology, and corporeality. Though not a Land Artist in the strict sense, Killi-Olsen’s grotesque, biomorphic figures often evoke an environmental consciousness—mutant hybrids that seem born of contaminated soil, folkloric unease, and ecological anxiety. His sculptures and installations suggest that nature is no longer a pure space of transcendence, but one marked by mutation, distortion, and historical violence. In this, Killi-Olsen exemplifies a broader shift in Norwegian environmental art: from romantic reverence to critical ambivalence.

More literal interventions in the landscape were undertaken by artists such as Bård Breivik (1948–2016), whose site-specific installations and sculptural forms engaged directly with geological processes and historical materials. Breivik’s Column Project (initiated in the 1990s), which involved the erection of monolithic stone pillars in various locations, draws on ancient megalithic traditions while reimagining them within a modern sculptural idiom. His materials—stone, wood, metal—are handled with a sensitivity to both tactility and context. Unlike the bombast of some American earthworks, Breivik’s interventions are quiet, deliberate, and imbued with a sense of ritual. They mark the landscape without dominating it.

Equally emblematic is the work of Marianne Heske (b. 1946), whose practice traverses installation, video, and conceptual art, often returning to the tension between permanence and transience, nature and artifice. Her most famous project, Prosjekt Gjerdeløa (1980), involved transporting a 17th-century log cabin from the Norwegian countryside to the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, exhibiting it as a found object, and then returning it to its original site. This act of displacement and recontextualization raised profound questions about authenticity, cultural heritage, and the meaning of “place.” It was a conceptual gesture that encapsulated much of what defines Norwegian Land Art: a minimalist aesthetic charged with historical and ecological resonance.

Photography, too, has played a central role in documenting and shaping the aesthetics of place. Artists like Dag Alveng, Tom Sandberg, and Per Maning used photography not merely as representation but as a mode of attention—a way of registering the slow temporality, muted light, and atmospheric density of Nordic environments. Their work often centers on landscapes emptied of spectacle: foggy fields, snowy roads, industrial peripheries. These images resist the picturesque, offering instead a phenomenological engagement with space. The viewer is not asked to admire but to dwell, to experience the land as duration and texture.