The Slade School of Fine Art was founded in 1871, a period rich with cultural transformation and the expansion of serious art education in Britain. This ambitious venture was made possible through the will of Felix Slade (1788–1868), a noted English philanthropist, lawyer, and collector, who bequeathed endowments to establish three professorships in fine art—one each at Oxford, Cambridge, and University College London (UCL). It was at UCL that the vision took root with lasting effect, giving birth to the Slade School. Felix Slade’s gift ensured that the new institution would have a financial and philosophical foundation grounded in serious academic pursuit rather than commercial art instruction.

The School was intended to rival the most prestigious art academies of Europe, offering rigorous training in drawing, sculpture, and painting. Unlike trade-oriented schools or guild-style training, the Slade emphasized life drawing and study from classical sculpture, upholding the notion that technical mastery was a prerequisite for creative freedom. It attracted not only aspiring artists but also leading intellectuals of the day, many of whom were aligned with the broader values of British liberal arts education, though the School itself maintained a firm commitment to objective standards. Its establishment marked a turning point in how Britain trained its artists, laying the groundwork for a lineage of modernist and realist talent.

Felix Slade, though not an artist himself, understood the vital role of art in national identity and education. Born in London in 1788, Slade amassed a notable collection of glassware, engravings, and books, much of which he left to the British Museum. His vision for the school was built on the classical belief that art should be both beautiful and truthful, and he invested in its long-term cultural influence. Slade died in 1868, never seeing the school open, but his legacy lives on in the halls of one of Britain’s most respected art institutions.

The decision to house the school within UCL gave it immediate academic credibility and placed it in the heart of London’s vibrant Bloomsbury district. It also ensured integration with scientific and humanist disciplines, fostering a culture where artists were encouraged to think, analyze, and innovate. From the outset, the Slade School represented more than a technical workshop—it was a place where thought and craftsmanship were intertwined. This founding ethos helped shape its unique identity, separating it from more bureaucratic or trade-focused institutions of the time.

The Early Years: Shaping Modern British Art

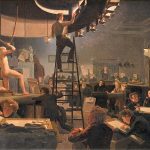

The Slade’s formative years were defined by the leadership of Sir Edward Poynter, who was appointed as the school’s first professor in 1871. Born in Paris in 1836 and trained at the Royal Academy and in Italy, Poynter brought with him an international sensibility and a deep reverence for classical art. His academic approach stressed the importance of drawing from life, anatomical accuracy, and disciplined composition. Under his direction, the Slade began developing a distinct reputation as a center of technical excellence and artistic seriousness.

Another pivotal figure in the early development of the Slade was Alphonse Legros, a French-born artist who began teaching at the school in 1876. Legros had trained in Paris and was deeply influenced by French realism and the revival of etching. His presence introduced a European flair to the Slade and aligned its methods more closely with Continental standards. He emphasized the moral and philosophical dimensions of art, challenging students to depict not just appearances, but inner truth. Legros’ tenure lasted until 1893, during which he left a lasting imprint on the school’s aesthetic values.

One of the most progressive features of the early Slade School was its decision to admit women on equal terms with men. This was a radical move in the late 19th century, as most formal art training excluded or marginalized female students. The coeducational environment fostered a spirit of inclusion that brought in major female artists like Gwen John and Winifred Knights. Their success helped dispel the myth that women could not handle serious academic art training, further cementing the Slade’s reputation as an institution ahead of its time.

By the close of the 19th century, the “Slade tradition” had fully emerged—a unique blend of classical rigor and creative independence. This approach set the school apart from the more rigid Royal Academy and the freer ateliers of Paris. Students were expected to master drawing and composition before moving on to personal exploration. The resulting combination of structure and expression shaped generations of British artists and laid the groundwork for modernism in the UK.

Notable Alumni and Influential Faculty

The Slade School’s alumni list reads like a who’s who of 20th-century British art, and its influence stretches across generations. Stanley Spencer, born in 1891, studied at the Slade between 1908 and 1912, bringing a mystical realism to British painting with works like “The Resurrection, Cookham.” Gwen John (1876–1939) and her brother Augustus John (1878–1961) were both prominent early students whose talents blossomed under the school’s demanding instruction. While Gwen John became known for her delicate, introspective portraits, Augustus carved a more flamboyant path, embracing bohemian life and producing bold, expressive works.

Another transformative figure to emerge from the Slade was Dora Carrington (1893–1932), who studied there during a period of artistic upheaval and personal exploration. Carrington’s time at the Slade from 1910 to 1914 was pivotal in shaping her identity as both a painter and a key member of the Bloomsbury Group. In the later 20th century, artists like Paula Rego, born in Lisbon in 1935, and Antony Gormley, born in 1950, brought international recognition to the Slade. Rego’s narrative-driven, feminist-informed paintings broke new ground in visual storytelling, while Gormley’s monumental sculptures like “Angel of the North” redefined British public art.

Faculty also played an essential role in shaping Slade’s legacy. William Coldstream, who directed the school from 1949 to 1975, was a painter committed to observational realism. His leadership helped implement significant curriculum reforms, encouraging a more intellectual and interdisciplinary approach to fine art training. Coldstream was instrumental in producing the Coldstream Report, which laid the foundation for university-level art education in the UK. Under his guidance, the Slade moved away from the narrow confines of studio practice and into broader academic legitimacy.

Among the faculty, Lucian Freud deserves special mention. Though his tenure at the Slade was brief, Freud’s reputation and penetrating portraiture cast a long shadow. His association with the school further cemented its reputation for supporting technically excellent, psychologically charged work. The relationships between instructors and students often developed into mentorships that continued beyond graduation, perpetuating a lineage of artistic excellence. Through this cycle of rigorous training and personal guidance, the Slade produced generation after generation of leading artists.

Teaching Philosophy and Curriculum

The Slade School’s teaching philosophy has always revolved around observational drawing, the human figure, and disciplined studio practice. From the beginning, drawing from life was seen not only as a technical exercise but also as a means of learning to see the world truthfully. The school’s instructors believed that an artist’s eye must be trained to perceive form, proportion, and movement in their most natural states. This commitment to drawing remains a cornerstone of the curriculum even today.

In the 1960s, William Coldstream’s advocacy for educational reform culminated in the publication of the Coldstream Report. This report laid out a framework for awarding degrees in art, thereby legitimizing art education in the eyes of traditional academia. Coldstream’s influence encouraged a more structured and analytical approach to visual arts, including written analysis and critical discussion. The Slade’s curriculum soon reflected this model, combining studio work with art history, theory, and critique.

Over time, the school incorporated more contemporary practices into its curriculum. By the 1980s and 1990s, students were encouraged to explore photography, video, installation, and performance alongside traditional painting and sculpture. These expansions did not mean abandoning core principles but rather adapting them to new forms. The result was a curriculum that balanced tradition with experimentation, appealing to a broader range of talents and interests.

Class sizes at the Slade have remained small, preserving the close-knit, master-apprentice style of instruction. This model fosters strong relationships between tutors and students, allowing for tailored feedback and in-depth discussion. Group critiques, peer reviews, and one-on-one mentorships are regular components of the academic year. Through these processes, students not only develop their technical abilities but also learn to articulate and defend their artistic decisions—a skill critical to any professional artist’s success.

Wartime and Post-War Transformation

World War II had a profound impact on the Slade School of Fine Art, both logistically and emotionally. During the war, the school was evacuated to Oxford as London faced bombings and severe disruption. Many faculty members and students enlisted or were otherwise engaged in the war effort, and classes were significantly reduced. Despite these challenges, the school continued operating, albeit on a smaller and more fragmented scale.

The post-war return to London marked a period of rebuilding and reflection. Under William Coldstream’s leadership, the Slade entered a golden era of renewal and seriousness. Returning veterans, many of whom had experienced the horrors of war firsthand, brought a new level of introspection and commitment to their work. The school’s emphasis on realism, particularly Coldstream’s observational methodology, found fertile ground in this environment of national soul-searching.

This era also saw a shift in the types of subject matter students engaged with. Rather than focusing solely on classical themes or idealized landscapes, students began exploring scenes from daily life, urban hardship, and personal narrative. The grittier realities of post-war Britain—rationing, rebuilding, and social change—provided new material for artistic reflection. The Slade’s curriculum responded by supporting more narrative, documentary styles, especially in painting and printmaking.

Many artists from this period would go on to define post-war British art, bringing with them the technical training and philosophical outlook instilled by the Slade. Their work emphasized not only the visual truth of what they saw but also a moral and emotional truth shaped by global conflict. The school became a bastion for figurative art at a time when abstraction was dominating the international scene. This insistence on grounding art in lived experience helped maintain the Slade’s reputation for seriousness and substance.

Slade in the Contemporary Art World

In recent decades, the Slade School of Fine Art has successfully adapted to the shifting tides of the global art world. Its student body has grown more diverse, reflecting the internationalization of higher education and the increasing accessibility of elite institutions. Artists now come from across the globe to study in London, and the Slade’s influence stretches far beyond the British Isles. This diversity enriches the classroom dynamic and brings fresh perspectives to traditional instruction.

The School has embraced the challenges and opportunities presented by contemporary art. Installation, video, and performance art are now standard areas of study, alongside the more time-honored disciplines. Digital media and artificial intelligence are also being explored, ensuring that the Slade remains at the forefront of innovation. Even as it integrates these new technologies, the institution remains grounded in its original values of integrity, discipline, and artistic truth.

Many contemporary Slade graduates have gone on to achieve critical acclaim in major art competitions and exhibitions. Several alumni have won or been shortlisted for the Turner Prize, Britain’s most prestigious contemporary art award. Others have represented the UK at the Venice Biennale or have been featured in leading galleries like the Tate Modern, Whitechapel Gallery, and the Serpentine. These accomplishments underline the Slade’s continuing relevance and impact on the modern art world.

Collaborations with major institutions like the British Council, the Royal Academy, and international museums help students engage with the professional art scene even before graduation. These partnerships offer valuable exposure and experience, allowing young artists to network, exhibit, and build their reputations. The school’s alumni network further supports emerging talent through mentorship and collective exhibitions. In this way, the Slade remains not only a place of learning but also a vital part of the global art ecosystem.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

The Slade School of Fine Art continues to hold an esteemed position within both British and international art circles. Its reputation for excellence in training, rigorous intellectual engagement, and artistic freedom makes it a benchmark for other institutions. Students who graduate from the Slade are known for their technical competence, thoughtful practice, and creative integrity. These qualities continue to make them competitive in a highly globalized and commercialized art world.

The school’s commitment to drawing and observational skills has not waned, even in an era dominated by digital media and conceptual experimentation. This adherence to foundational techniques distinguishes Slade graduates from those of more trend-driven institutions. At the same time, the Slade has proven adaptable, integrating new media and critical theory without sacrificing its core mission. This balance has allowed it to evolve without losing its identity.

Recent years have seen the emergence of artists like Phyllida Barlow and Douglas Gordon, who have contributed significantly to the school’s ongoing legacy. Barlow, known for her large-scale sculptural installations, served as a professor at the Slade before achieving widespread acclaim. Gordon, a Turner Prize winner, has helped redefine the possibilities of video and conceptual art. Their achievements affirm the school’s continued influence on high-level contemporary practice.

Today, the Slade remains a top choice for young artists who seek a serious and holistic education in the fine arts. Its combination of classical instruction, modern exploration, and critical inquiry ensures that it will continue shaping the future of art for generations to come. Even as the world changes, the Slade stands as a beacon of disciplined creativity and enduring cultural significance.

Key Takeaways

- The Slade School was founded in 1871 through the vision and endowment of Felix Slade.

- Its early coeducational model was groundbreaking for the time and supported by top-tier faculty.

- Alumni like Gwen John, Paula Rego, and Antony Gormley brought international recognition.

- The curriculum blends traditional drawing with modern media and conceptual rigor.

- It remains one of the most prestigious art institutions in the United Kingdom today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- When was the Slade School of Fine Art founded?

It was founded in 1871 through an endowment from Felix Slade. - Who are some of the school’s most famous alumni?

Notable names include Augustus John, Paula Rego, Antony Gormley, and Gwen John. - Is the Slade part of a university?

Yes, it is part of University College London (UCL), one of the UK’s top universities. - What makes its teaching approach unique?

It combines observational drawing with innovative, interdisciplinary practices. - Has the Slade influenced British art?

Profoundly—it has helped shape modern and contemporary British art since the 19th century.