Edward Hopper, one of the most iconic American painters of the 20th century, has a remarkable ability to create works that linger in the mind. His paintings are celebrated for their stark realism, evocative use of light, and scenes that feel both familiar and deeply unsettling. Viewers often describe a sense of unease when looking at his art—a feeling that’s hard to pin down yet impossible to ignore. What is it about Hopper’s work that leaves us with this haunting emotional resonance? Let’s explore the key elements of his style and themes to uncover why his paintings affect us so profoundly.

The Quiet Loneliness of Hopper’s World

At the heart of Hopper’s work is a profound exploration of isolation. His paintings frequently depict lone figures in settings such as cafés, motels, office spaces, or empty streets. Even when multiple characters share the frame, they seem emotionally detached, lost in their own worlds. This isolation is palpable and deeply human, making it relatable to anyone who has ever felt alone, even in a crowd.

“Nighthawks” and the Diner That Never Sleeps

Hopper’s most famous work, “Nighthawks” (1942), encapsulates this sense of solitude perfectly. The painting shows a late-night diner illuminated by fluorescent light, its four occupants disconnected from one another. The streets outside are eerily empty, and the glass walls of the diner make the scene feel almost like a diorama—separating the viewer from the action yet forcing them to observe. There’s no clear narrative, but the tension is unmistakable. What are these people thinking? Why are they here at this hour? The absence of answers is part of what makes the painting so haunting.

The Solitary Gaze in “Morning Sun”

In “Morning Sun” (1952), a woman sits alone on her bed, staring out of a window. The sunlight pours into the room, yet there’s no warmth in the scene. Her posture is rigid, her face contemplative, and the emptiness around her suggests a life paused in reflection. Hopper’s characters often feel like this—trapped in a moment, caught between worlds, and yet strangely timeless.

Hopper’s exploration of solitude resonates because it feels uncomfortably familiar. We recognize ourselves in these moments of quiet disconnection, and it forces us to confront our own vulnerabilities.

The Mystery of Hopper’s Ambiguity

Hopper’s paintings are like puzzles without solutions. He gives us a moment frozen in time and leaves us to fill in the blanks. This ambiguity—this refusal to provide a clear narrative—creates an emotional tension that can be deeply unsettling.

What’s Happening in “Office at Night”?

Take “Office at Night” (1940) as an example. The painting shows a man seated at a desk while a woman stands by a filing cabinet. There’s no interaction between them, but the spatial arrangement and the expressions on their faces suggest a charged atmosphere. Is there a romantic tension between them? Are they colleagues embroiled in a conflict? Hopper gives no answers, only hints. This lack of resolution forces the viewer to sit with the uncertainty, which can feel disconcerting.

The Power of Unanswered Questions

This ambiguity is not accidental. Hopper once said, “If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.” His works are intentionally open-ended, inviting viewers to project their own stories and emotions onto the scenes. Yet this freedom to interpret also creates discomfort, as the human mind craves resolution. The absence of answers leaves us unsettled, as if we’ve stumbled upon a moment we shouldn’t have seen but can’t look away from.

Light and Space: The Uncanny Glow

Hopper’s use of light is as much a character in his paintings as the people he depicts. He often employs harsh, artificial lighting or exaggerated sunlight to create stark contrasts and heightened emotional tension. His manipulation of light and shadow is meticulous, but it also feels slightly off, giving his works a surreal, dreamlike quality.

The Brightness of Isolation

In “Automat” (1927), a woman sits alone at a table, her face illuminated by an artificial light source. Behind her, a large window reflects only darkness, creating a jarring contrast between the brightly lit interior and the mysterious void outside. The scene feels isolated, vulnerable—like the woman is exposed while the world beyond remains unknowable. The artificial lighting heightens the sense of discomfort, making the familiar setting feel alien.

The Uncanny Spaces of “Rooms by the Sea”

Hopper’s “Rooms by the Sea” (1951) pushes this sense of disorientation even further. The painting shows a room with an open door leading directly to the sea. There’s no context to explain how or why this architectural impossibility exists—it simply is. The stark lighting, empty space, and surreal composition create a scene that feels both real and impossible, tapping into the psychological concept of the uncanny: the unsettling feeling of encountering something that’s almost—but not quite—familiar.

The Stasis of Time

Hopper’s paintings often feel suspended in time. His characters don’t move; his scenes don’t evolve. This frozen quality creates an eerie stillness that leaves viewers feeling trapped alongside the figures in the painting.

A World Paused

In many of Hopper’s works, such as “Gas” (1940) or “Cape Cod Evening” (1939), there’s no sense of motion or progress. The figures seem lost in thought, disconnected from their surroundings. The result is a feeling of timelessness—of moments stretched out indefinitely. While this stasis contributes to the dreamlike quality of his work, it also heightens the tension. The viewer is left waiting for something to happen, but it never does.

The Modern Condition: A Mirror for Ourselves

Hopper’s art is often described as a reflection of the human condition, particularly in the context of modern life. His paintings capture the disconnection, alienation, and quiet despair that often accompany urbanization and industrialization.

A Century of Relevance

During Hopper’s lifetime, urbanization was rapidly transforming the American landscape, and his work captured the emotional toll of these changes. Today, his themes feel just as relevant, if not more so, in an era of digital connectivity that often exacerbates feelings of isolation. Hopper’s ability to distill these universal emotions into his work is part of what makes it so impactful—and so unsettling.

The Voyeuristic Gaze

Finally, there’s the uncomfortable dynamic between the viewer and the scene. Hopper often positions the viewer as a voyeur, peering into private moments without permission. This uninvited perspective can feel intrusive, as if we’re complicit in observing something we shouldn’t.

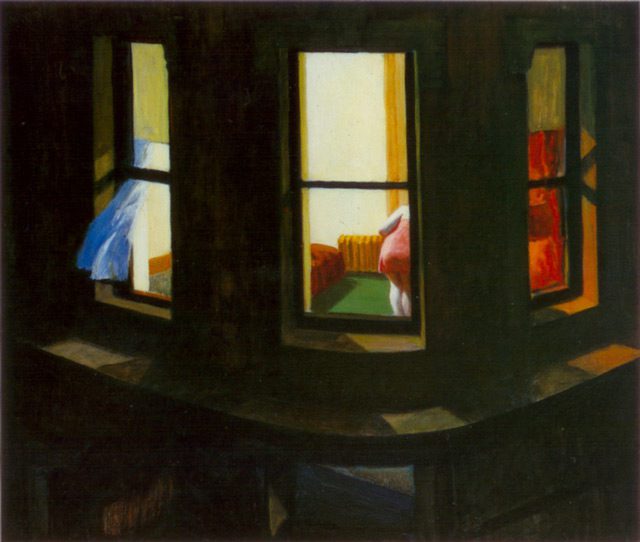

The Unease of “Night Windows”

In “Night Windows” (1928), we see a partial view of a woman inside her apartment, framed by a window. The angle of the painting suggests that we’re looking in from outside—a voyeuristic act that feels both intriguing and unsettling. This perspective forces the viewer to confront the ethics of their gaze, adding another layer of discomfort to the experience.

Why Hopper’s Unease Endures

Edward Hopper’s paintings leave us uneasy because they tap into universal truths about the human experience—our loneliness, our uncertainties, and our longing for connection. Through his use of isolation, ambiguity, light, and space, Hopper creates worlds that feel eerily familiar yet hauntingly distant. His art forces us to confront our own emotions and vulnerabilities, making the unease we feel not just a reaction to the paintings but a reflection of ourselves.

Key Takeaways

- Hopper’s focus on isolation and solitude resonates deeply with viewers, evoking a sense of loneliness.

- His ambiguous narratives leave stories unresolved, creating tension and unease.

- The use of stark lighting and uncanny spaces amplifies the emotional intensity of his works.

- Hopper’s paintings hold a mirror to the modern condition, reflecting timeless themes of alienation and disconnection.

By leaning into the unsettling, Hopper has created a body of work that continues to captivate and challenge viewers, making his art as relevant today as it was nearly a century ago.