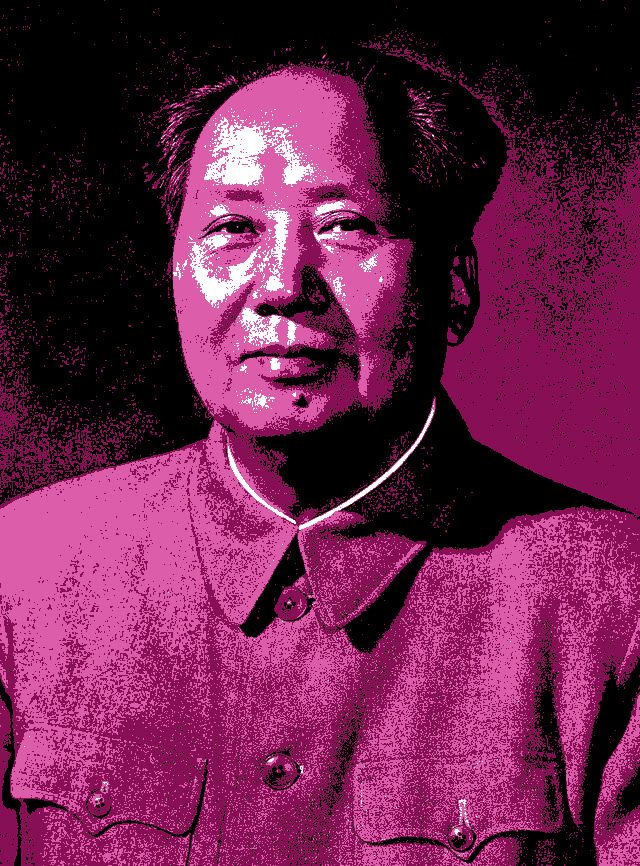

Let’s talk about a recurring theme in art galleries and fashion stores that never fails to raise eyebrows: Mao Zedong, splashed across canvases and T-shirts, his face reimagined in garish colors and abstract strokes. For many artists, Mao’s image is a shortcut to edginess, a loaded symbol of power, rebellion, and irony. But here’s the uncomfortable truth—this so-called “artistic statement” can often feel more like a shallow gimmick, skimming over a tragic reality.

The Origins: How Mao Became Pop Culture Chic

This strange trend has its roots in the 1970s, with none other than Andy Warhol. Warhol painted Mao’s face like he did Campbell’s soup cans—big, bold, and practically screaming for attention. Warhol’s Mao was ironic, casting the face of a brutal dictator as a commercial icon in the same league as a soda can. It was meant to make us think about the cult of personality and how even the most sinister figures can be packaged and sold like any other brand.

Since then, Mao’s face has been recast as an aesthetic choice, found everywhere from galleries to fashion boutiques. For some, Mao represents anti-capitalism or a rebellion against authority. For others, it’s simply “edgy,” a bold statement to stir things up. But is this usage of Mao’s image really as profound as it seems? Or is it just another example of shock value over substance?

The Problem with Mao as an “Edgy” Statement

Mao Zedong wasn’t just any controversial figure; he was responsible for an estimated 70 to 100 million deaths. Take a moment to really absorb that number—more people than live in most countries. His policies led to the Great Leap Forward, a disaster that saw millions starve to death, and the Cultural Revolution, a time of extreme purges, brutal repression, and lasting scars on China’s social fabric. So, when his face is plastered in neon on a canvas or screen-printed on a hoodie, one has to wonder: does this art actually make a point, or is it just ignorant of history?

Imagine if other brutal dictators had the same treatment—if Stalin, Pol Pot, or Hitler were stylized into pop art. It’s almost unthinkable. Yet, somehow, Mao has slipped through the cracks, his image recast as a trendy, detached icon rather than a reminder of real human suffering.

What Exactly Are Artists Trying to Say with Mao’s Image?

Let’s break down some of the reasons artists gravitate toward Mao’s image—and where these justifications fall short.

1. Shock Value

Nothing gets people talking like a controversial image. But let’s be honest, using Mao’s face just for shock value feels lazy. Sure, it makes people stop and look, but at what cost? Without a meaningful message behind the shock, it comes off as shallow, even disrespectful to the millions who suffered under his rule.

2. Irony and Pop Culture

Many artists lean on irony to explain their use of Mao. Warhol did it; why not them? Yet irony has a way of losing its punch when stripped of context. Recasting Mao as a pop icon is like reducing tragedy to kitsch—it’s fun to look at but ultimately hollow, especially if the artist doesn’t grapple with the weight of what Mao represents.

3. Anti-Capitalist Symbolism

Some artists argue Mao’s image is a critique of capitalism itself—a reminder of the dangers of ideological worship and unchecked political authority. But if Mao’s face is being sold on a $500 designer shirt or hung in a high-end gallery, that anti-capitalist critique feels more than a little hypocritical. Is it truly rebellion, or is it capitalism co-opting symbols of rebellion?

4. The Cult of Personality

Mao’s cult of personality was staggering—his face was once worshiped by millions, symbolizing a god-like authority. Artists may see Mao as the ultimate icon of control and manipulation, a warning about the dangers of personality cults. But again, when removed from context, this potent symbolism is watered down, like reducing a dark legacy to a convenient logo.

Where’s the Line Between Art and Exploitation?

Art should challenge us, even make us uncomfortable. But there’s a fine line between meaningful provocation and exploiting history’s darkest chapters for aesthetics. When artists use Mao’s face without acknowledging the sheer scale of the human suffering he caused, they risk trivializing real trauma. The image becomes just another trendy piece, more about surface than substance.

Using Mao as a statement without substance glosses over the tragedy of 70 to 100 million lives lost. It’s not just in poor taste—it’s a dangerous oversight that sanitizes history. When you strip away the human reality, Mao’s face becomes yet another visual soundbite, an empty icon devoid of the very meaning it once held.

The Takeaway: Art with Responsibility

Mao as an artistic statement walks a very thin line between commentary and insensitivity. If an artist wants to engage with his image, they need to do so with respect for the massive legacy of suffering behind it. Throwing his face on a canvas or T-shirt just to look provocative? That’s not rebellion—it’s exploitation. Next time you see Mao in a gallery or boutique, ask yourself: is this piece inviting us to reflect on history, or is it just trading in on shock value?

Art has the power to spark change and conversation, but when it comes to figures like Mao, a little sensitivity goes a long way. After all, using history’s darkest symbols as throwaway statements doesn’t just make for shallow art; it risks erasing the very lessons we should never forget.