Harriet Backer was born on January 21, 1845, in the small town of Holmestrand, Norway. Situated by the Oslofjord, this serene coastal town would have provided the young Harriet with her earliest visual memories: the soft, diffused light of Nordic skies, the tranquil waters, and the small-town charm that later permeated her works. Born into a well-off family, Backer enjoyed an upbringing that encouraged both intellectual pursuits and artistic growth. Her father, Nils Backer, was a merchant, while her mother, Sofie Smith Petersen, came from a family with strong cultural ties. Together, they fostered an environment rich in curiosity and learning.

Harriet was one of four children, and her siblings played significant roles in her artistic development. Her younger sister, Agathe Backer Grøndahl, later gained fame as a pianist and composer, establishing the Backer family as a household of notable creatives in Norway. Agathe’s accomplishments in music likely inspired Harriet’s early love for the arts, helping her develop a well-rounded appreciation for creativity, which later emerged as one of her defining traits as a painter.

Despite these early inclinations, Backer did not rush into an art career. It wasn’t until she was 30 years old—a relatively late age for a career artist—that she truly committed to painting. The delay wasn’t due to a lack of talent, but rather an intense desire for mastery. This careful approach set Backer apart from her peers, as she prioritized quality and depth over rushing into the art scene.

Formal Education: Studying Abroad in Paris

Backer’s formal art education began in 1867 when she moved to Christiania (now Oslo) and enrolled in a private painting academy run by Johan Fredrik Eckersberg, a celebrated Norwegian painter. Eckersberg had studied with some of the most influential figures in the European art world, and his emphasis on Romanticism and realism left an impression on Backer’s early work.

In the early 1870s, Backer’s artistic journey took her to Munich, then a thriving hub for Norwegian and Scandinavian artists seeking continental exposure. She studied at the women’s art academy run by Bertha Wegmann, a Danish painter who was an influential figure among female artists in Germany. This period in Munich was crucial, as it gave Backer exposure to a more formal style of painting—one that emphasized academic precision and attention to light and shadow. Yet, this rigorous, structured approach wasn’t enough for the ambitious painter.

In 1878, she moved to Paris, where she found the artistic freedom she craved. She studied at Léon Bonnat’s studio, a painter who championed naturalism and was known for his portraits. Paris was the epicenter of the art world in the late 19th century, and Backer soaked in the vibrant energy of the French capital. It was here, in the City of Light, that her style took a distinct turn toward Impressionism. She became fascinated with how light transformed everyday scenes and how this could be translated onto canvas. Her works began to carry the hallmarks of Impressionism: the focus on the fleeting effects of light, the emphasis on mood over meticulous detail, and the capturing of ordinary life.

Artistic Maturity: Mastering Light and Shadow

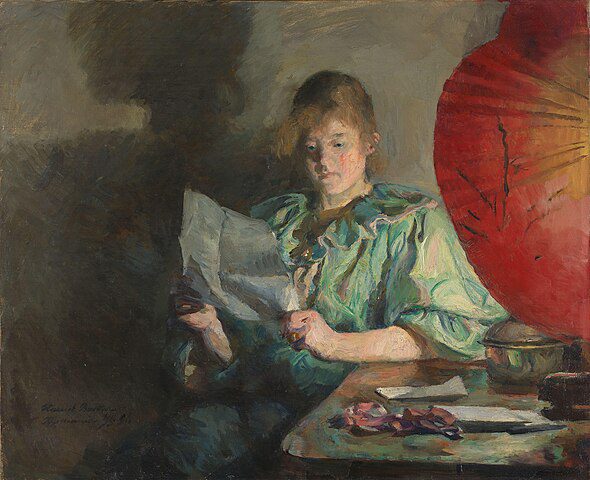

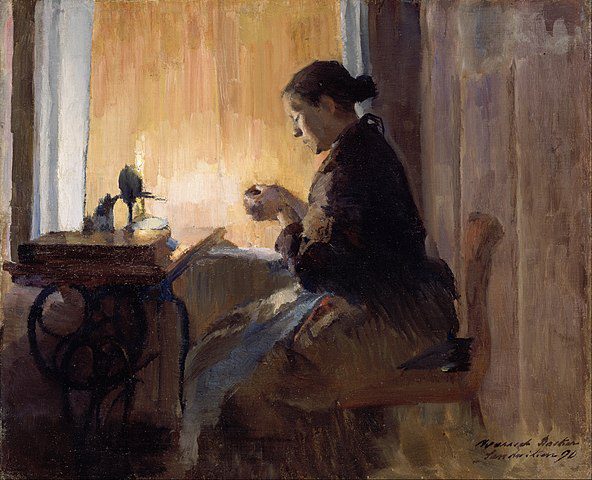

Harriet Backer’s mature period began in the late 1880s when she returned to Norway after years of honing her craft in Paris. During this time, she painted some of her most famous works, such as Blue Interior (1883) and Chez Moi (1887). What stood out in Backer’s work was her ability to manipulate light. Unlike the French Impressionists, who often worked outdoors, Backer focused on interior scenes, exploring how light entered a room and bathed everyday objects in different tones and hues.

Her works often featured women in quiet, contemplative moments—reading, writing, or simply absorbed in thought. These domestic scenes, tinged with a poetic calmness, became her signature. Backer didn’t strive for dramatic subjects. Instead, she found beauty in the mundane and often overlooked details of life. The way sunlight filtered through a curtain or the shadows cast by a window frame became central to her compositions. In a world where art was still predominantly male-dominated, Harriet Backer carved out her niche by showing the quiet strength of the everyday, particularly through the lens of women’s lives.

One of her contemporaries, painter Christian Krohg, once said of Backer: “She paints as though she breathes.” His words were not just a compliment to her skill but also a reflection of how effortless her depictions of light and shadow appeared. Backer’s paintings, like Sunshine in the Blue Room (1891), highlight her technical mastery but also her emotional sensitivity toward the subjects she painted.

Challenges in the Norwegian Art Scene

Backer’s return to Norway wasn’t without its difficulties. The art scene in Norway in the late 19th century was still developing, and there was limited recognition for female artists, even one as accomplished as Backer. Furthermore, Impressionism hadn’t yet taken hold in the country’s more conservative art circles. While artists like Edvard Munch were beginning to gain international recognition, Backer’s quieter, more introspective style struggled to break through to a wider audience.

But Backer never wavered in her commitment to her artistic vision. In fact, she became a mentor to younger Norwegian artists, including the aforementioned Munch. She taught at the art school in Kristiania (Oslo), where she emphasized the importance of learning from both nature and the great masters. Her pedagogical influence on Norway’s next generation of painters solidified her legacy as more than just a painter, but also as an educator and pioneer for female artists in the country.

Personal Life and Relationships: The Quiet Heartbeat Behind the Brush

Harriet Backer never married or had children, choosing instead to dedicate her life to her art. She formed close relationships with several of her peers, including fellow Norwegian artists such as Kitty Kielland, who shared her interest in capturing the beauty of the natural and domestic world. Kielland and Backer often painted together, inspiring each other’s works in a way that suggests a deep, collaborative friendship.

Though some biographers have speculated about possible romantic relationships in her life, the primary focus of her existence seemed to revolve around her work. Backer’s commitment to painting was steadfast, and she never allowed personal distractions to interfere with her artistic career. In this way, she exemplified the single-minded focus that characterized many of the great artists of her time.

Despite being somewhat introverted, Backer was known to be a warm and generous mentor. Her quiet dedication earned her the respect and admiration of her peers, even if she didn’t always enjoy the same level of fame as some of her male counterparts. Harriet Backer remained a humble figure in the Norwegian art world, a quiet force whose influence extended far beyond her own work.

A Pioneer for Women in Art

Harriet Backer was not a vocal advocate for women’s rights, but her life and career spoke volumes. In an era when few women pursued professional careers in the arts, she not only succeeded but also earned respect in male-dominated circles. Her quiet determination to develop her craft and produce meaningful art without conforming to societal expectations placed her ahead of her time.

Her role as a teacher was significant in shaping the future of Norwegian art. She provided mentorship and guidance to many young women who, like her, sought to break into the art world despite societal barriers. Her ability to blend Impressionist influences with a distinctly Norwegian sensibility made her a unique figure, both in Norway and on the broader European art stage.

The Norwegian artist Asta Nørregaard once said, “Harriet Backer led by example; she didn’t need to shout to be heard.” This quote captures the essence of Backer’s legacy. She may not have been as loud or as revolutionary as some of her contemporaries, but her impact was undeniable. She carved out a space for women in Norwegian art through sheer dedication, persistence, and unwavering artistic integrity.

Legacy and Later Life: A Quiet Departure

In the later years of her life, Harriet Backer’s health began to decline, but she continued to paint well into her seventies. She remained in Oslo, quietly working on her art and mentoring younger painters. Though she never reached the international fame that other Norwegian artists like Edvard Munch or Gustav Vigeland achieved, her influence on the Norwegian art scene was profound.

Backer died on March 25, 1932, at the age of 87. She left behind a body of work that continues to be celebrated for its emotional depth and technical brilliance. Though her fame has always been quieter than some of her contemporaries, her legacy as a pioneer for female artists and a master of light and shadow endures.

In 2009, her work was exhibited in the National Gallery in Oslo as part of a retrospective that sought to celebrate her contributions to Norwegian art. Today, Harriet Backer is remembered not only as one of Norway’s finest painters but as an artist who captured the delicate beauty of everyday life with unparalleled grace.

The Unseen Power of Harriet Backer

In a time when male artists dominated the conversation, Harriet Backer proved that it was possible to create a lasting legacy through perseverance, skill, and an unwavering commitment to one’s vision. Her work may not have the dramatic flair of some of her more famous contemporaries, but it carries a quiet power that resonates with those who take the time to look closer.

Backer’s focus on the intimate moments of life—the way light plays on a window sill, or how a figure contemplates a letter—shows us the beauty that exists in the world around us. And in this, Harriet Backer remains an artist for the ages, a woman who painted the world as she saw it and left an indelible mark on Norwegian and European art.