In the hushed corridors of 19th-century Russian aristocracy, Marianne von Werefkin emerged as a trailblazer, a woman whose artistic journey would carve a distinct path in the annals of Expressionism. Born on September 10, 1860, into a noble family in Tula, Russia, Marianne was destined to defy the conventions of her time and embrace a life of artistic exploration.

The von Werefkin household, steeped in privilege and tradition, fostered Marianne’s early appreciation for the arts. Her parents, both of Baltic-German descent, recognized her artistic inclination and provided her with the tools to nurture her talent. The walls of their estate echoed with the strokes of Marianne’s youthful brush as she painted the world around her with an intuitive flair.

Marianne’s artistic aspirations faced resistance from her conservative family, who viewed the pursuit of art as a frivolous endeavor unbecoming of her noble status. Undeterred, she embarked on a courageous journey, seeking formal artistic training against her family’s wishes. She enrolled at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, challenging societal norms that prescribed a more conventional path for a woman of her background.

At the academy, Marianne crossed paths with fellow student Alexej von Jawlensky, a meeting that would prove pivotal to her personal and artistic evolution. The connection between the two burgeoning artists deepened, and they formed a bond that transcended the confines of traditional mentorship. Their artistic dialogue laid the foundation for a partnership that would shape the trajectory of Marianne’s creative life.

However, fate, like the intricate strokes on a canvas, would introduce a tumultuous chapter into Marianne’s life. In 1889, she married Russian military officer and amateur artist Vasiliy Kandinsky. The marriage was an attempt to conform to societal expectations and appease her family, yet it brought emotional turbulence. Kandinsky, though supportive of her artistic pursuits, struggled with Marianne’s fierce independence and determination.

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, a seismic shift occurred within Marianne’s artistic vision. The couple, Marianne and Kandinsky, sought inspiration from the burgeoning avant-garde movements sweeping across Europe. Marianne found herself drawn to the revolutionary ideas of the Symbolists, a movement that rejected literal representation in favor of conveying emotions and spiritual experiences through art.

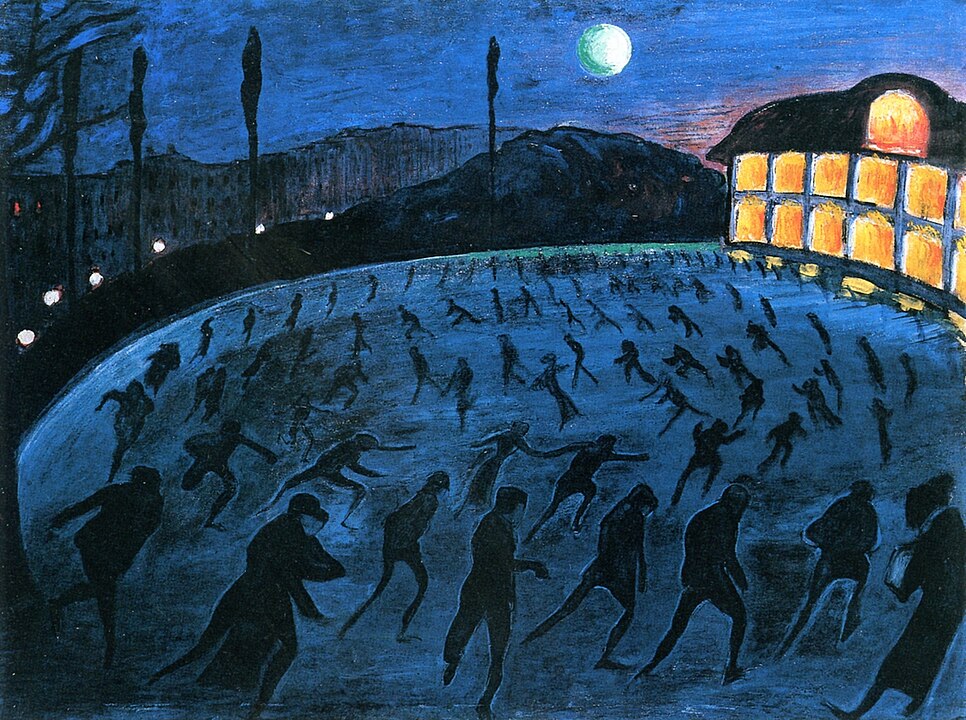

In the early 20th century, the couple encountered the effervescent atmosphere of Munich, a city teeming with artistic experimentation and cultural fervor. It was here, amid the vibrant artistic community, that Marianne and Kandinsky, along with other like-minded artists, founded the avant-garde group known as “Der Blaue Reiter” (The Blue Rider). This collective sought to break free from the academic constraints of the time and explore new realms of artistic expression.

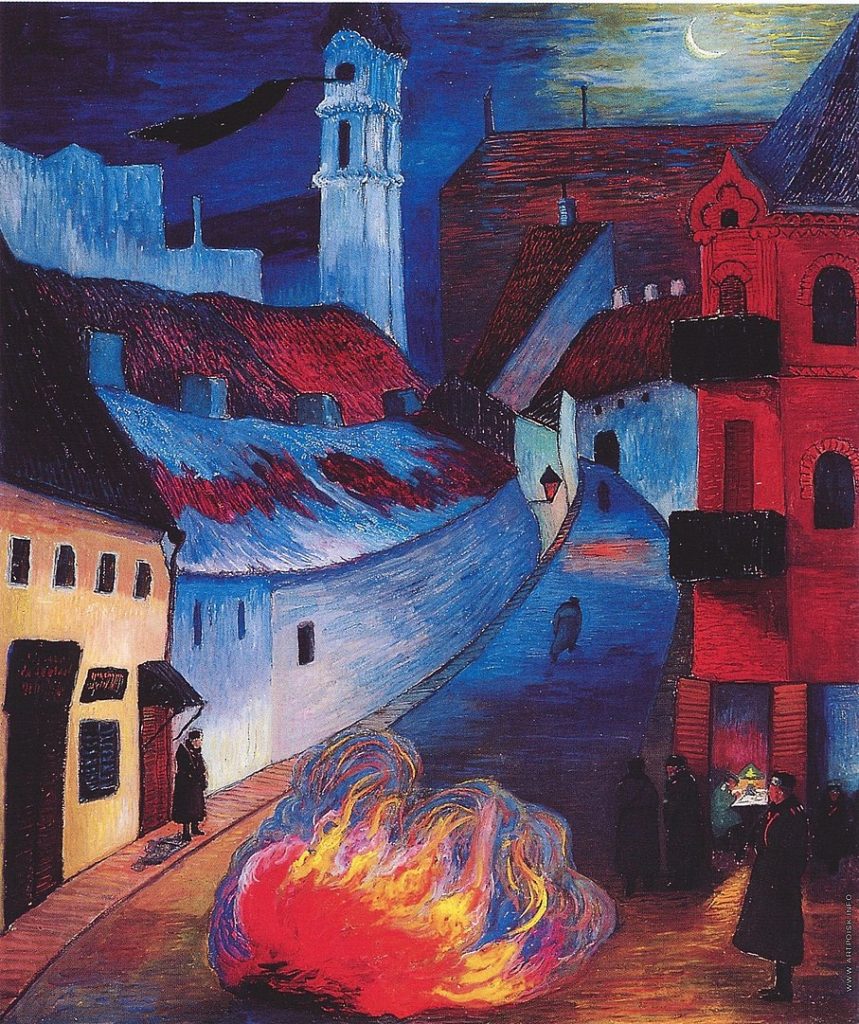

Marianne’s work during this period was characterized by vivid colors, bold compositions, and a departure from representational norms. Her canvases became a visual symphony, harmonizing emotional depth with the avant-garde spirit. She delved into the realms of spirituality and mysticism, themes that permeated her work and reflected her profound inner journey.

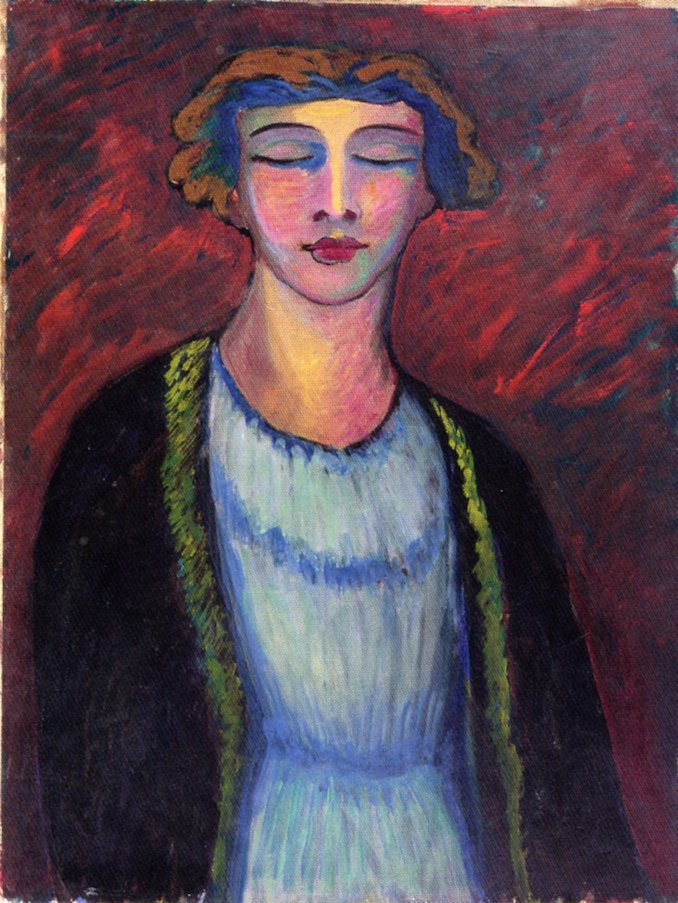

The Blue Rider group, through their almanac and exhibitions, became a conduit for the dissemination of modernist ideas. Marianne, with her distinctive voice, contributed significantly to the group’s ethos. Her 1910 self-portrait, a masterful exploration of color and form, stands as a testament to her ability to transcend traditional portraiture and communicate a complex emotional state.

However, the onset of World War I and the subsequent Russian Revolution thrust Marianne into a tumultuous period of displacement. The von Werefkin-Kandinsky union, strained by personal and artistic differences, unraveled, leading to the couple’s separation. Marianne, grappling with the upheavals of war and the disintegration of her marriage, found solace in Switzerland, where she retreated to the picturesque surroundings of Ascona.

In Ascona, Marianne established the artist colony “Die Russen” (The Russians), a sanctuary for artists seeking refuge from the chaos of war. Here, amid the serene landscapes, she continued to paint with unwavering dedication, her art evolving to capture the essence of the Swiss scenery and the emotional tumult of the times.

The interwar years witnessed a renaissance in Marianne’s work. Her artistic language matured, marked by a nuanced exploration of form and color. The Alpine landscapes, bathed in the ethereal glow of her palette, became a recurring motif. Through her prolific output, Marianne demonstrated an ability to synthesize personal emotions with the external environment, creating canvases that resonated with viewers on a deeply emotive level.

As the shadows of war receded, Marianne experienced a late but well-deserved recognition of her contributions to the art world. Her works found their way into prestigious exhibitions, cementing her status as a pioneering figure in the Expressionist movement. In 1924, she participated in the influential “Exhibition of the Unknown Painter” in Berlin, a showcase that celebrated the diversity and innovation of modernist artists.

The 1930s brought both acclaim and retrospection for Marianne. Her artistic legacy, coupled with her distinctive personal style—marked by her iconic headscarves and voluminous dresses—made her a celebrated figure. Yet, the political landscape of Europe cast its ominous shadow. The rise of the National Socialist regime in Germany, with its disdain for modernist art, posed a threat to artists like Marianne, whose work embodied the spirit of the avant-garde.

Forced into exile, Marianne sought refuge in Switzerland once again. Her artistic output continued, a testament to her resilience and unwavering commitment to her craft. The turbulent years had not dimmed her creative fervor; if anything, they had imbued her work with a profound gravitas and introspection.

Marianne von Werefkin passed away on February 6, 1938, leaving behind a body of work that defied artistic norms and bore witness to the transformative power of the human spirit. Her legacy, once overshadowed by the prominence of male counterparts, has experienced a renaissance in recent decades, with renewed scholarly interest in her contributions to the Expressionist movement.

Beyond the strokes of her brush, Marianne’s life unfolded as a narrative of audacity, resilience, and an unwavering pursuit of artistic truth. In her journey, she defied societal expectations, challenged artistic conventions, and forged a path that would inspire generations of artists to come. Marianne von Werefkin, the trailblazer with the headscarf and the palette, remains an enduring figure in the pantheon of modernist pioneers, a testament to the transformative power of art in the face of adversity.